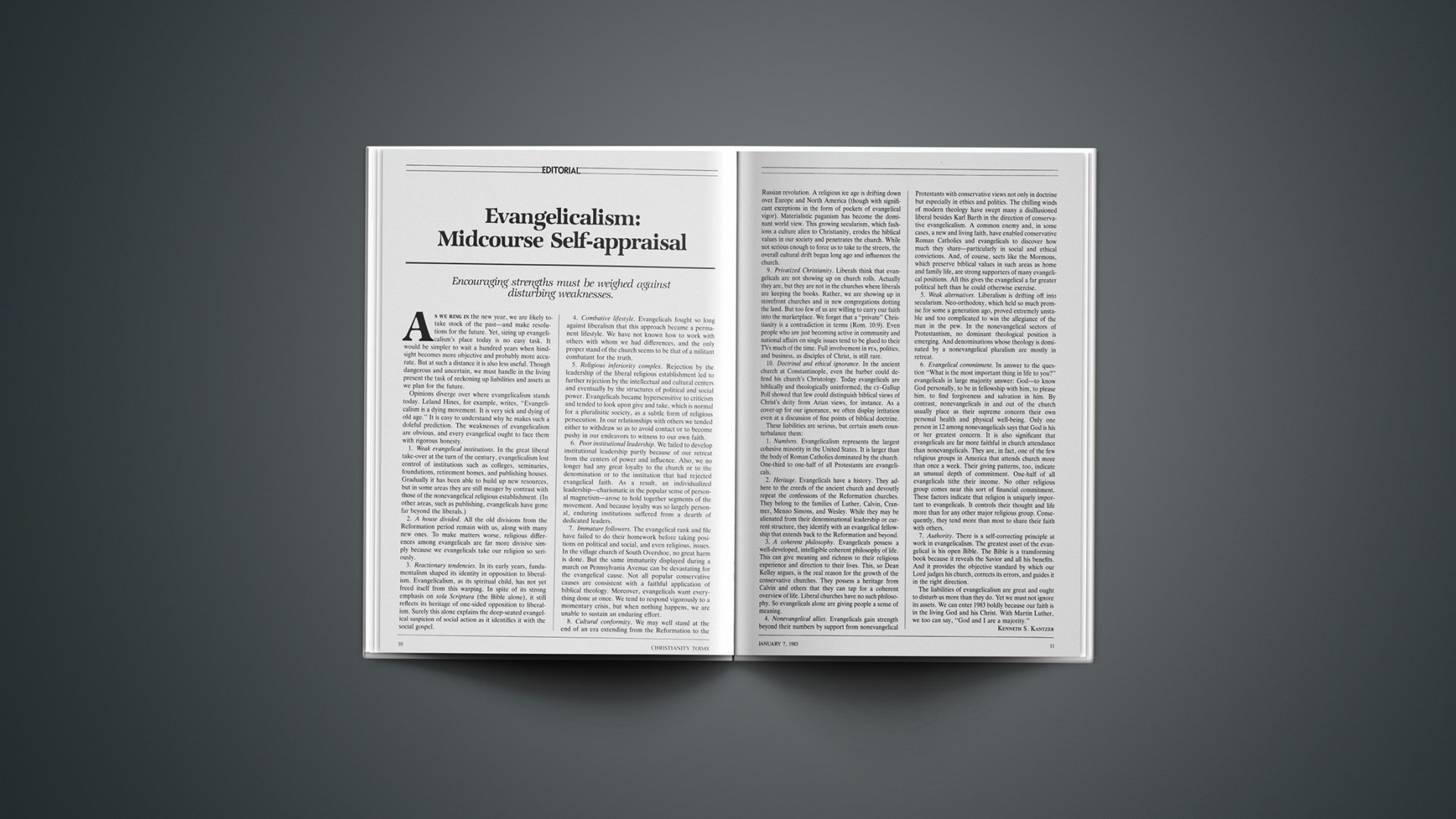

Encouraging strengths must be weighed against disturbing weaknesses.

As we ring in the new year, we are likely to-take stock of the past—and make resolutions for the future. Yet, sizing up evangelicalism’s place today is no easy task. It would be simpler to wait a hundred years when hindsight becomes more objective and probably more accurate. But at such a distance it is also less useful. Though dangerous and uncertain, we must handle in the living present the task of reckoning up liabilities and assets as we plan for the future.

Opinions diverge over where evangelicalism stands today. Leland Hines, for example, writes, “Evangelicalism is a dying movement. It is very sick and dying of old age.” It is easy to understand why he makes such a doleful prediction. The weaknesses of evangelicalism are obvious, and every evangelical ought to face them with rigorous honesty.

1. Weak evangelical institutions. In the great liberal take-over at the turn of the century, evangelicalism lost control of institutions such as colleges, seminaries, foundations, retirement homes, and publishing houses. Gradually it has been able to build up new resources, but in some areas they are still meager by contrast with those of the nonevangelical religious establishment. (In other areas, such as publishing, evangelicals have gone far beyond the liberals.)

2. A house divided. All the old divisions from the Reformation period remain with us, along with many new ones. To make matters worse, religious differences among evangelicals are far more divisive simply because we evangelicals take our religion so seriously.

3. Reactionary tendencies. In its early years, fundamentalism shaped its identity in opposition to liberalism. Evangelicalism, as its spiritual child, has not yet freed itself from this warping. In spite of its strong emphasis on sola Scriptura (the Bible alone), it still reflects its heritage of one-sided opposition to liberalism. Surely this alone explains the deep-seated evangelical suspicion of social action as it identifies it with the social gospel.

4. Combative lifestyle. Evangelicals fought so long against liberalism that this approach became a permanent lifestyle. We have not known how to work with others with whom we had differences, and the only proper stand of the church seems to be that of a militant combatant for the truth.

5. Religious inferiority complex. Rejection by the leadership of the liberal religious establishment led to further rejection by the intellectual and cultural centers and eventually by the structures of political and social power. Evangelicals became hypersensitive to criticism and tended to look upon give and take, which is normal for a pluralisitic society, as a subtle form of religious persecution. In our relationships with others we tended either to withdraw so as to avoid contact or to become pushy in our endeavors to witness to our own faith.

6. Poor institutional leadership. We failed to develop institutional leadership partly because of our retreat from the centers of power and influence. Also, we no longer had any great loyalty to the church or to the denomination or to the institution that had rejected evangelical faith. As a result, an individualized leadership—charismatic in the popular sense of personal magnetism—arose to hold together segments of the movement. And because loyalty was so largely personal, enduring institutions suffered from a dearth of dedicated leaders.

7. Immature followers. The evangelical rank and file have failed to do their homework before taking positions on political and social, and even religious, issues. In the village church of South Overshoe, no great harm is done. But the same immaturity displayed during a march on Pennsylvania Avenue can be devastating for the evangelical cause. Not all popular conservative causes are consistent with a faithful application of biblical theology. Moreover, evangelicals want everything done at once. We tend to respond vigorously to a momentary crisis, but when nothing happens, we are unable to sustain an enduring effort.

8. Cultural conformity. We may well stand at the end of an era extending from the Reformation to the Russian revolution. A religious ice age is drifting down over Europe and North America (though with significant exceptions in the form of pockets of evangelical vigor). Materialistic paganism has become the dominant world view. This growing secularism, which fashions a culture alien to Christianity, erodes the biblical values in our society and penetrates the church. While not serious enough to force us to take to the streets, the overall cultural drift began long ago and influences the church.

9. Privatized Christianity. Liberals think that evangelicals are not showing up on church rolls. Actually they are, but they are not in the churches where liberals are keeping the books. Rather, we are showing up in storefront churches and in new congregations dotting the land. But too few of us are willing to carry our faith into the marketplace. We forget that a “private” Christianity is a contradiction in terms (Rom. 10:9). Even people who are just becoming active in community and national affairs on single issues tend to be glued to their TVs much of the time. Full involvement in PTA, politics, and business, as disciples of Christ, is still rare.

10. Doctrinal and ethical ignorance. In the ancient church at Constantinople, even the barber could defend his church’s Christology. Today evangelicals are biblically and theologically uninformed; the CT-Gallup Poll showed that few could distinguish biblical views of Christ’s deity from Arian views, for instance. As a cover-up for our ignorance, we often display irritation even at a discussion of fine points of biblical doctrine.

These liabilities are serious, but certain assets counterbalance them:

1. Numbers. Evangelicalism represents the largest cohesive minority in the United States. It is larger than the body of Roman Catholics dominated by the church. One-third to one-half of all Protestants are evangelicals.

2. Heritage. Evangelicals have a history. They adhere to the creeds of the ancient church and devoutly repeat the confessions of the Reformation churches. They belong to the families of Luther, Calvin, Cranmer, Menno Simons, and Wesley. While they may be alienated from their denominational leadership or current structure, they identify with an evangelical fellowship that extends back to the Reformation and beyond.

3. A coherent philosophy. Evangelicals possess a well-developed, intelligible coherent philosophy of life. This can give meaning and richness to their religious experience and direction to their lives. This, so Dean Kelley argues, is the real reason for the growth of the conservative churches. They possess a heritage from Calvin and others that they can tap for a coherent overview of life. Liberal churches have no such philosophy. So evangelicals alone are giving people a sense of meaning.

4. Nonevangelical allies. Evangelicals gain strength beyond their numbers by support from nonevangelical Protestants with conservative views not only in doctrine but especially in ethics and politics. The chilling winds of modern theology have swept many a disillusioned liberal besides Karl Barth in the direction of conservative evangelicalism. A common enemy and, in some cases, a new and living faith, have enabled conservative Roman Catholics and evangelicals to discover how much they share—particularly in social and ethical convictions. And, of course, sects like the Mormons, which preserve biblical values in such areas as home and family life, are strong supporters of many evangelical positions. All this gives the evangelical a far greater political heft than he could otherwise exercise.

5. Weak alternatives. Liberalism is drifting off into secularism. Neo-orthodoxy, which held so much promise for some a generation ago, proved extremely unstable and too complicated to win the allegiance of the man in the pew. In the nonevangelical sectors of Protestantism, no dominant theological position is emerging. And denominations whose theology is dominated by a nonevangelical pluralism are mostly in retreat.

6. Evangelical commitment. In answer to the question “What is the most important thing in life to you?” evangelicals in large majority answer: God—to know God personally, to be in fellowship with him, to please him, to find forgiveness and salvation in him. By contrast, nonevangelicals in and out of the church usually place as their supreme concern their own personal health and physical well-being. Only one person in 12 among nonevangelicals says that God is his or her greatest concern. It is also significant that evangelicals are far more faithful in church attendance than nonevangelicals. They are, in fact, one of the few religious groups in America that attends church more than once a week. Their giving patterns, too, indicate an unusual depth of commitment. One-half of all evangelicals tithe their income. No other religious group comes near this sort of financial commitment. These factors indicate that religion is uniquely important to evangelicals. It controls their thought and life more than for any other major religious group. Consequently, they tend more than most to share their faith with others.

7. Authority. There is a self-correcting principle at work in evangelicalism. The greatest asset of the evangelical is his open Bible. The Bible is a transforming book because it reveals the Savior and all his benefits. And it provides the objective standard by which our Lord judges his church, corrects its errors, and guides it in the right direction.

The liabilities of evangelicalism are great and ought to disturb us more than they do. Yet we must not ignore its assets. We can enter 1983 boldly because our faith is in the living God and his Christ. With Martin Luther, we too can say, “God and I are a majority.”