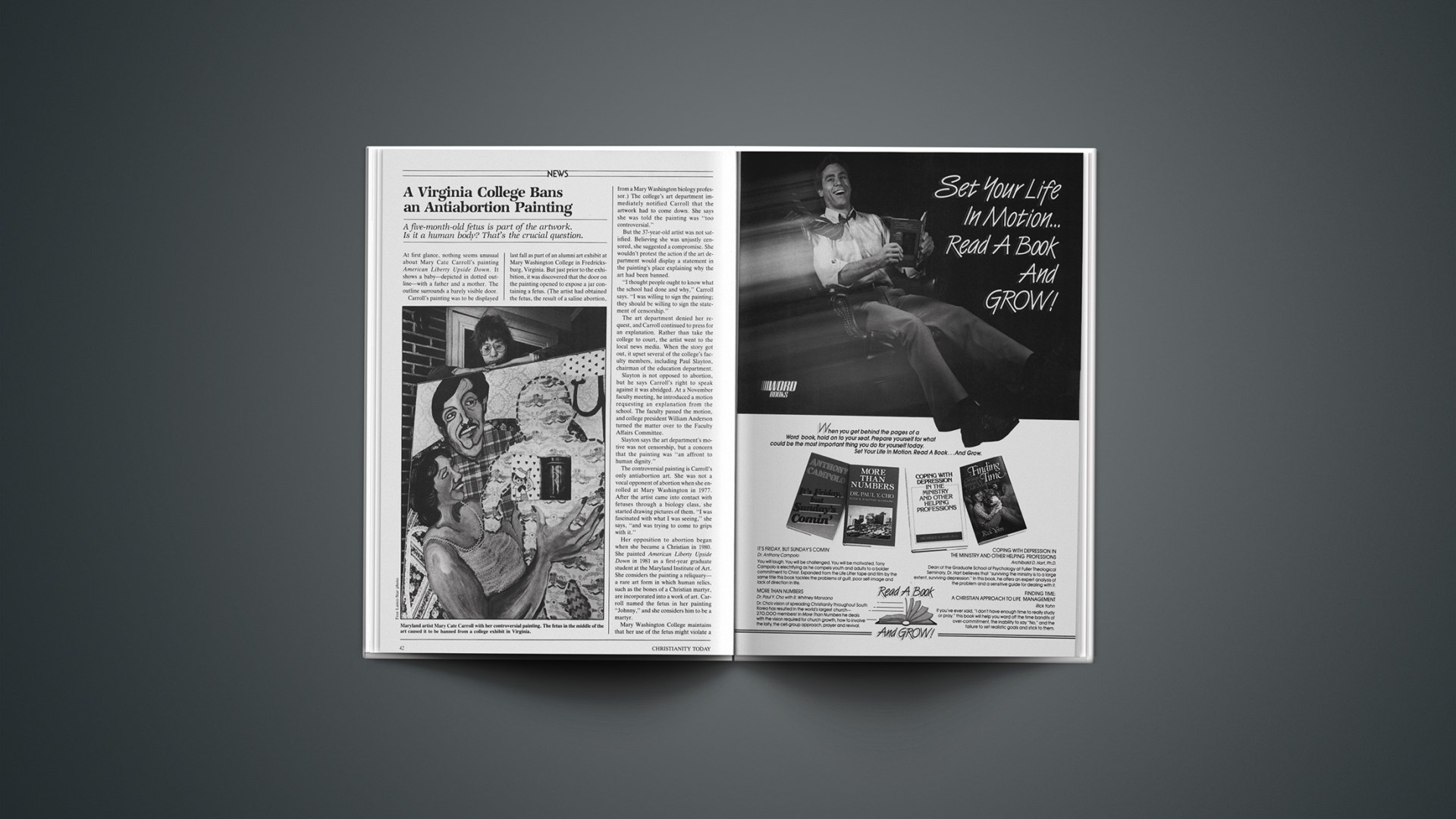

A five-month-old fetus is part of the artwork. Is it a human body? That’s the crucial question.

At first glance, nothing seems unusual about Mary Cate Carroll’s painting American Liberty Upside Down. It shows a baby—depicted in dotted outline—with a father and a mother. The outline surrounds a barely visible door.

Carroll’s painting was to be displayed last fall as part of an alumni art exhibit at Mary Washington College in Fredricksburg, Virginia. But just prior to the exhibition, it was discovered that the door on the painting opened to expose a jar containing a fetus. (The artist had obtained the fetus, the result of a saline abortion, from a Mary Washington biology professor.) The college’s art department immediately notified Carroll that the artwork had to come down. She says she was told the painting was “too controversial.”

But the 37-year-old artist was not satisfied. Believing she was unjustly censored, she suggested a compromise. She wouldn’t protest the action if the art department would display a statement in the painting’s place explaining why the art had been banned.

“I thought people ought to know what the school had done and why,” Carroll says. “I was willing to sign the painting; they should be willing to sign the statement of censorship.”

The art department denied her request, and Carroll continued to press for an explanation. Rather than take the college to court, the artist went to the local news media. When the story got out, it upset several of the college’s faculty members, including Paul Slayton, chairman of the education department.

Slayton is not opposed to abortion, but he says Carroll’s right to speak against it was abridged. At a November faculty meeting, he introduced a motion requesting an explanation from the school. The faculty passed the motion, and college president William Anderson turned the matter over to the Faculty Affairs Committee.

Slayton says the art department’s motive was not censorship, but a concern that the painting was “an affront to human dignity.”

The controversial painting is Carroll’s only antiabortion art. She was not a vocal opponent of abortion when she enrolled at Mary Washington in 1977. After the artist came into contact with fetuses through a biology class, she started drawing pictures of them. “I was fascinated with what I was seeing,” she says, “and was trying to come to grips with it.”

Her opposition to abortion began when she became a Christian in 1980. She painted American Liberty Upside Down in 1981 as a first-year graduate student at the Maryland Institute of Art. She considers the painting a reliquary—a rare art form in which human relics, such as the bones of a Christian martyr, are incorporated into a work of art. Carroll named the fetus in her painting “Johnny,” and she considers him to be a martyr.

Mary Washington College maintains that her use of the fetus might violate a Virginia law regarding the disposition and control of dead human bodies and body parts.

In an address to the faculty, college president William Anderson said the decision to remove the controversial painting was based not on “moral, political, or philosophical considerations” but on concern for the law.

Anderson implied in his address that the college had sought expert legal opinion, including an interpretation from Virginia’s attorney general, before having the painting removed. But Carroll says she was not told about the possible violation of law until weeks after the exhibit had ended.

The artist has no plans to sue the college. But on her behalf, a lawyer is seeking an interpretation from the attorney general’s office of state laws governing the handling of dead bodies.

“I would feel good if they rule against me,” Carroll says. By ruling that she violated a law pertaining to dead bodies, she says, “it would mean they are saying that Johnny is a dead human body. And if there’s a body, it follows that there has to be a crime.”

Former Ncc Head Leaves Ministry Of The United Methodist Church

Former National Council of Churches (NCC) president James Armstrong has surrendered his credentials as a minister in the United Methodist Church. Last November, Armstrong resigned as United Methodist bishop of Indiana and as president of the NCC (CT, Dec. 16, 1983, p. 46).

Armstrong informed the church of his latest decision in a brief letter to the bishop who replaced him. By citing a provision in the church’s Book of Discipline. Armstrong left open the possibility that he might become a minister in another denomination. But he has not indicated that he plans to do so.

His withdrawal from the church’s ministry in January is believed to be unprecedented for a former United Methodist bishop. Church spokesman James Steele emphasized that Armstrong has not abandoned Christian service. He described Armstrong’s action as “a routine procedure for someone who wants to leave open the possibility of serving in another denomination.”

When he resigned as a United Methodist bishop last fall, Armstrong said he was “physically and emotionally depleted” due to “an exhausting and inhuman work schedule.” He is working as a counselor for international students at a community college in Fort Lauderdale, Florida.

March For Life

As many as 75,000 banner-waving demonstrators converged on Washington, D.C., January 23. The March for Life protested the 1973 U.S. Supreme Court decision Roe v. Wade, which legalized abortions. Since that ruling, some 15 million abortions have been performed in this country. The annual march attempts to rally support for a constitutional amendment to protect the rights of the unborn.

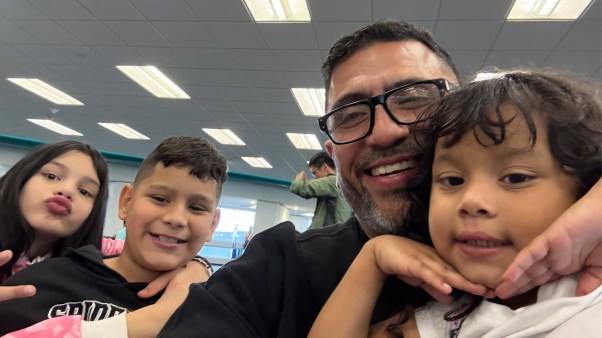

Photos, counterclockwise from top: Marchers walk from the White House to the Supreme Court building. U.S. Representative Henry Hyde (R-Ill.) speaks to the crowd. March leader Nellie Gray with Melody Green, widow of the late gospel singer Keith Green. The 1984 March for Life was the largest in recent years.