One year after the news media made Americans aware of the famine, there is both cause for concern and reason for hope.

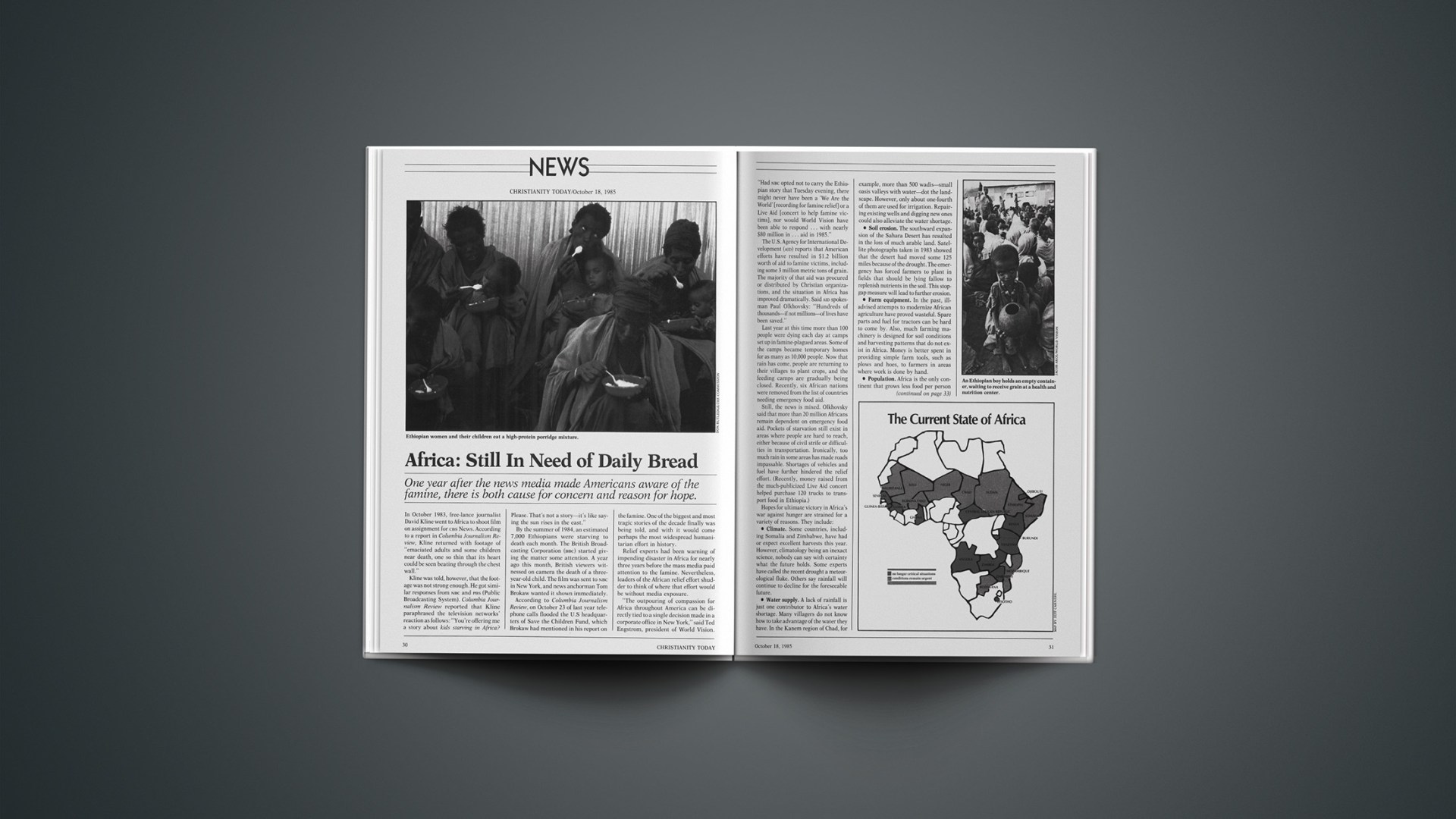

In October 1983, free-lance journalist David Kline went to Africa to shoot film on assignment for CBS News. According to a report in Columbia Journalism Review, Kline returned with footage of “emaciated adults and some children near death, one so thin that its heart could be seen beating through the chest wall.”

Kline was told, however, that the footage was not strong enough. He got similar responses from NBC and PBS (Public Broadcasting System). Columbia Journalism Review reported that Kline paraphrased the television networks’ reaction as follows: “You’re offering me a story about kids starving in Africa? Please. That’s not a story—it’s like saying the sun rises in the east.”

By the summer of 1984, an estimated 7,000 Ethiopians were starving to death each month. The British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) started giving the matter some attention. A year ago this month, British viewers witnessed on camera the death of a three-year-old child. The film was sent to NBC in New York, and news anchorman Tom Brokaw wanted it shown immediately.

According to Columbia Journalism Review, on October 23 of last year telephone calls flooded the U.S headquarters of Save the Children Fund, which Brokaw had mentioned in his report on the famine. One of the biggest and most tragic stories of the decade finally was being told, and with it would come perhaps the most widespread humanitarian effort in history.

Relief experts had been warning of impending disaster in Africa for nearly three years before the mass media paid attention to the famine. Nevertheless, leaders of the African relief effort shudder to think of where that effort would be without media exposure.

“The outpouring of compassion for Africa throughout America can be directly tied to a single decision made in a corporate office in New York,” said Ted Engstrom, president of World Vision. “Had NBC opted not to carry the Ethiopian story that Tuesday evening, there might never have been a ‘We Are the World’ [recording for famine relief] or a Live Aid [concert to help famine victims], nor would World Vision have been able to respond … with nearly $80 million in … aid in 1985.”

The U.S. Agency for International Development (AID) reports that American efforts have resulted in $1.2 billion worth of aid to famine victims, including some 3 million metric tons of grain. The majority of that aid was procured or distributed by Christian organizations, and the situation in Africa has improved dramatically. Said AID spokesman Paul Olkhovsky: “Hundreds of thousands—if not millions—of lives have been saved.”

Last year at this time more than 100 people were dying each day at camps set up in famine-plagued areas. Some of the camps became temporary homes for as many as 10,000 people. Now that rain has come, people are returning to their villages to plant crops, and the feeding camps are gradually being closed. Recently, six African nations were removed from the list of countries needing emergency food aid.

Still, the news is mixed. Olkhovsky said that more than 20 million Africans remain dependent on emergency food aid. Pockets of starvation still exist in areas where people are hard to reach, either because of civil strife or difficulties in transportation. Ironically, too much rain in some areas has made roads impassable. Shortages of vehicles and fuel have further hindered the relief effort. (Recently, money raised from the much-publicized Live Aid concert helped purchase 120 trucks to transport food in Ethiopia.)

Hopes for ultimate victory in Africa’s war against hunger are strained for a variety of reasons. They include:

• Climate. Some countries, including Somalia and Zimbabwe, have had or expect excellent harvests this year. However, climatology being an inexact science, nobody can say with certainty what the future holds. Some experts have called the recent drought a meteorological fluke. Others say rainfall will continue to decline for the foreseeable future.

• Water supply. A lack of rainfall is just one contributor to Africa’s water shortage. Many villagers do not know how to take advantage of the water they have. In the Kanem region of Chad, for example, more than 500 wadis—small oasis valleys with water—dot the landscape. However, only about one-fourth of them are used for irrigation. Repairing existing wells and digging new ones could also alleviate the water shortage.

• Soil erosion. The southward expansion of the Sahara Desert has resulted in the loss of much arable land. Satellite photographs taken in 1983 showed that the desert had moved some 125 miles because of the drought. The emergency has forced farmers to plant in fields that should be lying fallow to replenish nutrients in the soil. This stopgap measure will lead to further erosion.

• Farm equipment. In the past, ill-advised attempts to modernize African agriculture have proved wasteful. Spare parts and fuel for tractors can be hard to come by. Also, much farming machinery is designed for soil conditions and harvesting patterns that do not exist in Africa. Money is better spent in providing simple farm tools, such as plows and hoes, to farmers in areas where work is done by hand.

• Population. Africa is the only continent that grows less food per person than it did 20 years ago. It also is the only continent where the annual population growth rate increased (to about 2.7 percent) during the 1970s. Development experts point out that families in underdeveloped nations have children as “insurance,” since so few survive. In Angola, one in three children die by the age of five.

• Refugee problem. The large-scale displacement of people has hampered efforts to achieve economic stability. An estimated 1.4 million refugees, mostly from Chad, Uganda, and Ethiopia, are living in Sudan. More than 12,000 children live as vagrants in Khartoum, Sudan’s capital. The refugee problem frustrates efforts at education and basic agricultural training.

• Political strife. Civil war in some areas has inhibited the delivery of famine aid. Relief experts say it is simplistic to blame only the governments now in power. The division of Africa by European colonial powers in the late 1800s often was done without regard to cultural and tribal heritage. The resulting tensions have continued into the present.

The relief effort has been hampered further by the perception that donated grain is rotting in African ports. World Vision spokesman Brian Bird said that perception is based on “myopic reporting.… Sometimes there are delays, and there is always spoilage as there is with any cargo, but the overwhelming majority of food reaches people who need it.”

During the last year, the goal has been to keep people alive. Only recently has the effort shifted to development. “The major problem of a long-term relief situation such as this is that it can lead to dependency,” said Grady Mangham, senior associate executive director for international ministries at World Relief, Inc.

The relief arm of the National Association of Evangelicals, World Relief has addressed the dependency problem with its Food for Work program. Villagers are given food in exchange for work, such as building roads and dams, or digging wells. During the next three years, World Relief will oversee the digging of more than 100 wells to prepare for possible future droughts. The organization also is teaching people methods of reforestation. This includes planting “drought-resistant” trees that grow quickly and require less water to survive.

Development experts know from experience that such projects lack the drama required to catch the eye of major news organizations. World Vision is trying to rekindle media interest 12 months after NBC brought the crisis to the attention of the American public. World Vision has offered transportation by truck or plane to journalists who want to witness firsthand both the progress and the continuing problems in Africa.

The relief-and-development organization will make use of a satellite hookup during the last week of this month. A press conference broadcast by satellite from Ethiopia will give journalists in the United States a chance to interview Ethiopian government officials. The satellite will also be used to broadcast a fund-raising telethon to some 200 U.S. viewer markets. Television celebrity Gary Collins and his wife, former Miss America Mary Ann Mobley, will work in Ethiopia as moderators of “Ethiopia LIVE: One Year Later.”

The task of communicating the urgency of the situation in Africa is perhaps the biggest challenge that relief organizations face. “The average American just cannot empathize with these people,” Engstrom said, “without having swatted away the flies, smelled the air, and seen the filth.

“Babies have died literally minutes after they were in my arms,” he said. “I’ve held babies who, I knew, wished they could cry—to express that part of their being—but they didn’t have the strength.”

How Can Another African Famine Be Prevented?

Food distribution to famine-stricken areas of Africa is carried out by private, voluntary organizations, many of them church-related. They work in cooperation with the U.S. Agency for International Development (AID), which coordinates relief efforts with governments overseas. AID Director M. Peter McPherson talked to CHRISTIANITY TODAY about prospects for long-term development assistance that could prevent future bouts of mass starvation.

What are the goals of long-range economic development in Africa?

The biggest change that needs to be made in many countries is to pay farmers more for what they produce. Urbanites use their political power to get cheap food for themselves. That leads to an effective discrimination against farmers, who are usually the poorest people in a country. When that happens, a society reverts back to subsistence farming, or continues at that level.

Price increases do make a difference. In Somalia last year, price increases resulted in a 40 percent increase in sorghum production.

What are the prospects for seeing small businesses spring up in Africa?

An entrepreneurial revolution already is going on. Three things are occurring to produce an explosion of people working out of their homes throughout the Third World. First, the population explosion has made jobs scarce, so people have decided to make furniture or do handicrafts or go into some type of service activity. Second, governments are abandoning certain nationalized industries, which opens up private opportunities for people. Third, when farmers are paid more, they begin producing a bit extra and selling it.

We try to come up with ways to help this process continue. Sometimes we provide credit, sometimes we provide training, and most of all, we encourage governments to adopt economic policies favorable to these changes.

Do some African governments see this as a threat to their own ideologies?

Yes, but the reality is that their old system isn’t producing jobs. The way they can stay in power is to satisfy basic human needs. From the standpoint of market forces, we’ve made enormous strides in Africa in the last four or five years. The socialist model has been a dismal failure in Africa. With the drought, they have failed in terms of delivering food. We have delivered enormous amounts, and the people of Africa know it.

What will put these countries on a sustained course of economic well-being?

Agricultural production will be critical, and it can be stimulated by price increases and other factors. Previously, no one had put much money into figuring out how to increase production of sorghum or millet—poor people’s crops. But in the last four years, we have put about $75 million each year into increasing production of these crops, and we’re seeing results. In Sudan, increased sorghum production is going to increase the food that is available for consumption, and it’s also going to create a lot of entrepreneurs.

How soon can these countries anticipate real improvements?

I think Africa can be better in 10 years and remarkably better in 20. In India in 1966 there was a famine, which, in human terms, was much worse than the African famine. The Indians made some fundamental changes in their economic policies, and the technology of the green revolution came along with improved seeds. In addition, the World Bank and AID were spending money for irrigation projects there.

The Indian government’s policies—combined with our resources and technology—meant that India basically became self-sufficient in grain production. I’m not saying that everyone in India is well fed. But as a nation, it has turned its situation around. I do not believe the situation in Africa is fundamentally any worse than the situation India faced 20 years ago.

What are private-sector groups doing to promote long-term development in Africa?

Various groups are helping to build an irrigation system. Roads are being built, and reforestation projects are under way. The private, voluntary organizations work as contractors with AID, bidding to do different tasks, AID has 5,000 people in 65 countries and a budget of about $7 billion. We depend on private groups to carry out much of the work that needs to be done.