Since the U.S. Supreme Court ruling on Roe v. Wade in 1973, the abortion philosophy has sunk deeply into the American psyche. A generation of young American women has known abortion only as a legal right, not as a crime or desperate act. The task of restoring the sanctity of all life, fetal included, may seem impossible.

But in recent months, this has seemed more and more feasible. Before and since President Reagan’s re-election last November, Christians have been among those who have expressed increased hope about altering the nation’s abortion law. This hope hinges on the Supreme Court and Reagan’s expected appointment of antiabortion justices. We should understand, however, that even with the appointment of antiabortion justices, Roe is not likely to be reversed overnight. To avoid illusions, and thus encourage true and realistic hope, Christians who struggle to end abortion on demand need to know the answers to such questions as these:

• How, exactly, can the current legal situation be changed?

• What is involved in overturning a constitutional ruling?

• How long might it take?

• Is there a legal strategy that prolifers should keep in mind?

Possibilities For Ending Abortion On Demand

When the Supreme Court makes a decision regarding constitutional law, it can be changed in only two ways: by a constitutional amendment, or by the Court reversing itself. Amending the Constitution is a lengthy and rarely used process. (Only 26 amendments have been added to the Constitution.) More frequently, the Court will change its mind in a later case or, gradually, in a number of cases.

In our 200 years of history, the Court has explicitly overruled its earlier constitutional interpretations more than 100 times, an average of once every two years. Although a few decisions have been reversed a year or two after the original case, the average “life” of a constitutional mistake has been calculated as 24 years. (See “Abandoning Error,” by John T. Noonan, Jr., in Reversing Roe v. Wade, to be published in 1985.)

Reversing Roe

Reversal requires either that enough justices change their minds about the original decision to make a new majority, or that new members are appointed to the Court. The second possibility offers greater hope for overruling Roe.

The first hint of any change in the Court’s attitude came in a set of abortion cases in 1983, and from the newest member. Justice Sandra Day O’Connor dissented from the proabortion majority decision. (The Court struck down an “informed consent” regulation. That regulation required that information about fetal development, the abortion procedure, and its consequences be given to a woman considering an abortion.)

In her carefully reasoned dissent, Justice O’Connor declared that Roe v. Wade “is on a collision course with itself.” She apparently is willing to reverse Roe. Her dissent sparked interest in the possibility of a reversal by the Supreme Court itself rather than by constitutional amendment.

The arithmetic on overruling Roe is encouraging. Of the nine justices, the two original dissenters in Roe (Byron White, Jr., and William Rehnquist) still sit on the Court. Along with Justice O’Connor, they are the youngest members of the Court. Five of the original Roe majority are now over 76. Justice Blackmun, Roe’s author, warned that at least one, and possibly four, new justices will be appointed during the current presidential term. President Reagan has clearly stated his intention to appoint judges who respect the sanctity of human life. Since Justice John Paul Stevens and Chief Justice Warren Burger are open to persuasion against Roe, even one new justice could tip the balance to an anti-Roe majority.

But if the Supreme Court were to reverse Roe v. Wade, it is not likely that it would do so in a single decision. It is more likely that Roe would be reversed by a series of decisions, gradually eroding the original doctrine. Over time, it would become evident that little legal support remains. Such a reversal would require several cases, appealed to the Supreme Court, to present relevant abortion issues to the justices. On each appeal, the Court would have the opportunity to reverse decisively, or to take the smaller step of somehow limiting abortion.

No one can predict how long the process could take. It might span several generations. “Jim Crow” laws, for example, were approved by the Supreme Court in 1896 and not overruled until 1954. On the other hand, the Court has reversed itself within a year. More frequent are life spans of a few years, such as that of Minersville School District v. Gobitis. This 1940 ruling required that school children salute the flag and recite the Pledge of Allegiance, and it was overturned in 1943.

How Gradual Reversal Would Work

Just how would this gradual reversal work? A typical strategy begins with enactment of a law that regulates abortion in some way. Abortion-performing physicians would undoubtedly bring a lawsuit in federal district court to challenge the law. The decision of that court would be appealed to a circuit court by the losing party. The circuit court’s decision then would be appealed to the “court of last resort,” the Supreme Court.

This plan would attack Roe’s most vulnerable point, then proceed in subsequent cases to its best-defended position. And what is Roe’s weakest point?

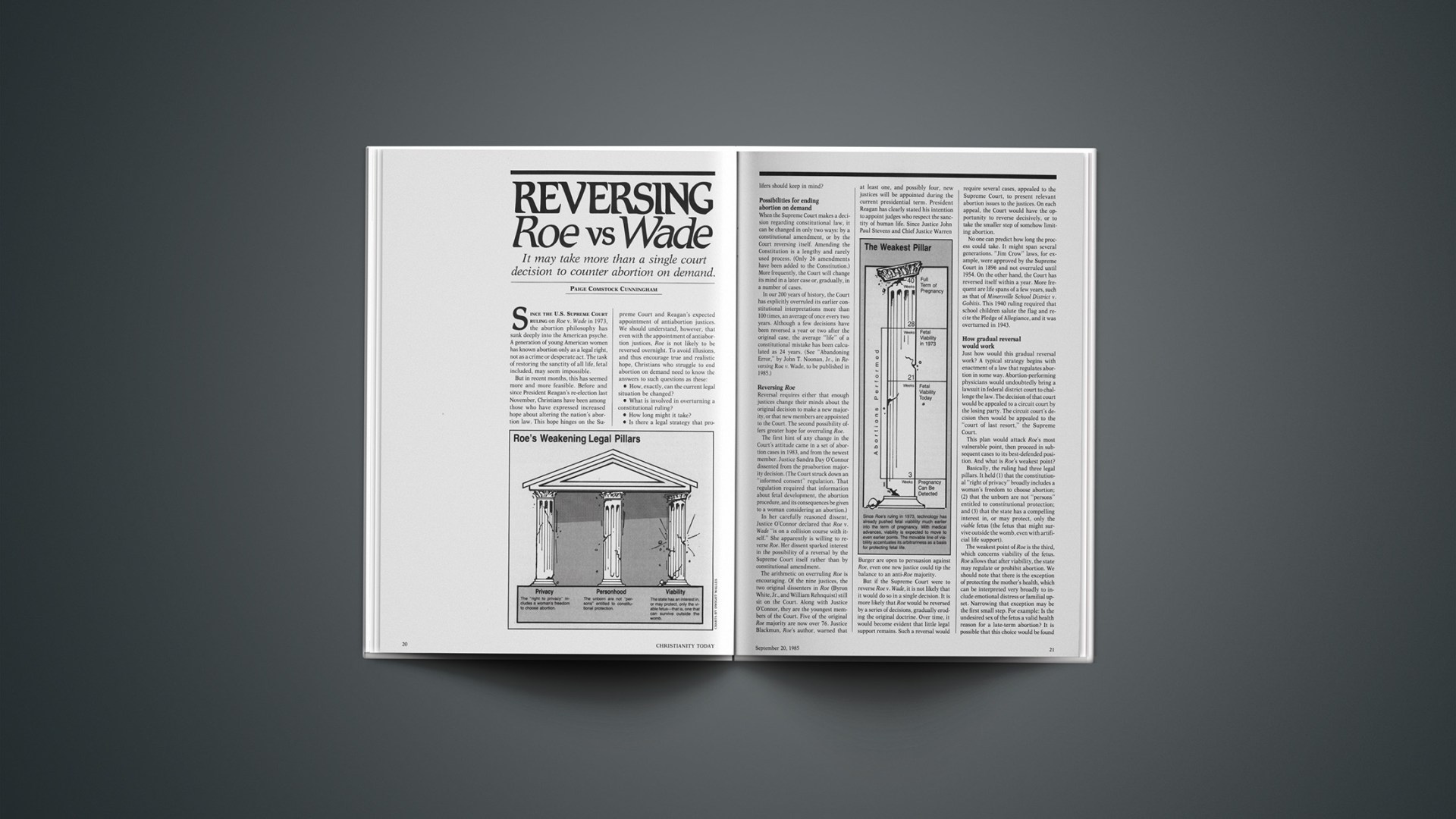

Basically, the ruling had three legal pillars. It held (1) that the constitutional “right of privacy” broadly includes a woman’s freedom to choose abortion; (2) that the unborn are not “persons” entitled to constitutional protection; and (3) that the state has a compelling interest in, or may protect, only the viable fetus (the fetus that might survive outside the womb, even with artificial life support).

The weakest point of Roe is the third, which concerns viability of the fetus. Roe allows that after viability, the state may regulate or prohibit abortion. We should note that there is the exception of protecting the mother’s health, which can be interpreted very broadly to include emotional distress or familial upset. Narrowing that exception may be the first small step. For example: Is the undesired sex of the fetus a valid health reason for a late-term abortion? It is possible that this choice would be found to be blatant sex discrimination.

In addition to narrowing the meaning of “therapeutic abortion,” this legal pillar can also be weakened by expanding the state’s interest in the unborn child. When the Court wrote in Roe that the state has a compelling interest in the viable fetus, it relied on medical evidence estimating viability at approximately 28 weeks. Medical advances since then have added nearly 8 weeks, moving viability to 20 or 21 weeks. Existing in vitro (“test tube baby”) fertilization technology, combined with the development of an artificial womb, could put viability at conception. The movable line of viability points up its arbitrariness as a basis for protecting the right to life. The Supreme Court eventually may abandon viability as a “factual” criterion concerning the right to abortion.

Scientific and medical developments challenge other factual premises. The Court called the fetus “potential life.” Yet, physicians now treat the child in the womb as a patient. Intrauterine blood transfusions can be done safely, and other fetal surgery is beyond the experimental stage. Photography of the unborn child compellingly illustrates its humanity, exploding the myth that the fetus is “just a blob of tissue.”

Recent attention to fetal pain adds to the prolife arsenal. If for no other reason than the humanitarian instincts that ban unanesthetized experimentation on animals, the abortion of the sensing, reacting, unborn child is objectionable. At the same time as these developments, the true physical health risks of pregnancy are being reduced. This challenges the Court’s assertion that abortion is safer than pregnancy and further limits the exceptions for therapeutic abortion.

Building On The First Step

To summarize: Medical technology may provide the factual tools for the assault on Roe, but the legal ammunition is set off by legislation. As we have said, a lawsuit on abortion rights is brought in response to a statute that regulates abortion in some way. In the words of Prof. Kenneth Ripple of the Notre Dame University School of Law, when a legislature finds that “life capable of existence outside of the uterus is in fact present” at an early stage of pregnancy, the courts “would be forced to confront [those] findings.”

Later cases would build on the legal victories of earlier cases. Ideally, the Supreme Court would not only declare that the state has a compelling interest in protecting fetal life from conception onward, it would also demolish the other two legal pillars of Roe by declaring that the “right of privacy” does not include abortion, and that the unborn are constitutional persons.

That would be the ideal. As a practical matter, the Court may stop short of guaranteeing the right to life of the unborn, and return (as before Roe) regulation of abortion to the states. This could create “abortion havens” in those states that continue to permit abortion. Some states might prohibit abortion with exceptions for rape, incest, or genuine physical health risk. Others might permit abortion only when the mother’s life is endangered.

The best initial step, at any rate, is legislation that nibbles away at the most vulnerable part of Roe’s liberal allowances for abortion. Innovative laws that may take us into the first phase of reversal strategy are currently being challenged in a lawsuit now before the Supreme Court (Diamond v. Charles). The law in question squarely presents the Court with the issue of state protection of the viable fetus. It also provides for a doctor prescribing birth control to inform the patient if the method is an abortifacient (that is, one that acts by causing abortion).

An Illinois law enacted in 1984 raises other significant issues by (1) barring sex-selective abortion; (2) providing for analgesics or anesthetics to relieve fetal pain during abortion; and (3) requiring that the viable fetus to be aborted be given the same medical care (if it survives the abortion) as a prematurely born child.

The Effects Of Law

Legalized abortion on demand was granted to American society by seven Supreme Court justices; only a majority of five is needed to remove it. But an underlying question remains: Even if the law is changed, will it change society’s attitudes and behavior against abortion?

In a society of shared values, law does have force in restraining or modifying behavior. In 1970, nearly 200,000 legal abortions were performed in those states that permitted it under certain circumstances. (The number of illegal abortions is speculative.) In the year following the Roe v. Wade decision legalizing abortion, nearly 750,000 women had abortions. Was there an immediate drastic change in morals? Or did women choose the easier solution of abortion simply because it was legal?

To look at it another way, if the speed limit were changed to 70 miles per hour, how many drivers would continue to observe the 55 mph guideline? Evidence is conclusive that lives and gasoline are saved by the lower limit. But most drivers admit to adhering to it only due to fear of punishment—the speeding ticket.

The law is a deterrent. Even more significant, the law is a reflection of the values we as a society want to protect. Even if an antiabortion law were more a statement of principle than an enforceable protection, it would enshrine the value of the sanctity of human life—that we as a civilized people will protect the most innocent and helpless among us. Otherwise, we are no better than barbarians where power is the arbiter of values, and the unborn child no more than property.

In conclusion, let me remind Christians that the struggle against abortion is not solely a legal one. An essential element of the prolife movement is education in churches and schools. Realistic alternatives to abortion must continue, providing services such as shepherding homes for unwed mothers, counseling, job placement, free medical care, maternity and baby clothes, and single parenting classes. Spiritual needs are just as critical as physical ones, and perhaps more difficult to meet. Christians must be the salt and light of the abortion issue. Ours is the voice of compassion, and thus the compulsion to change.