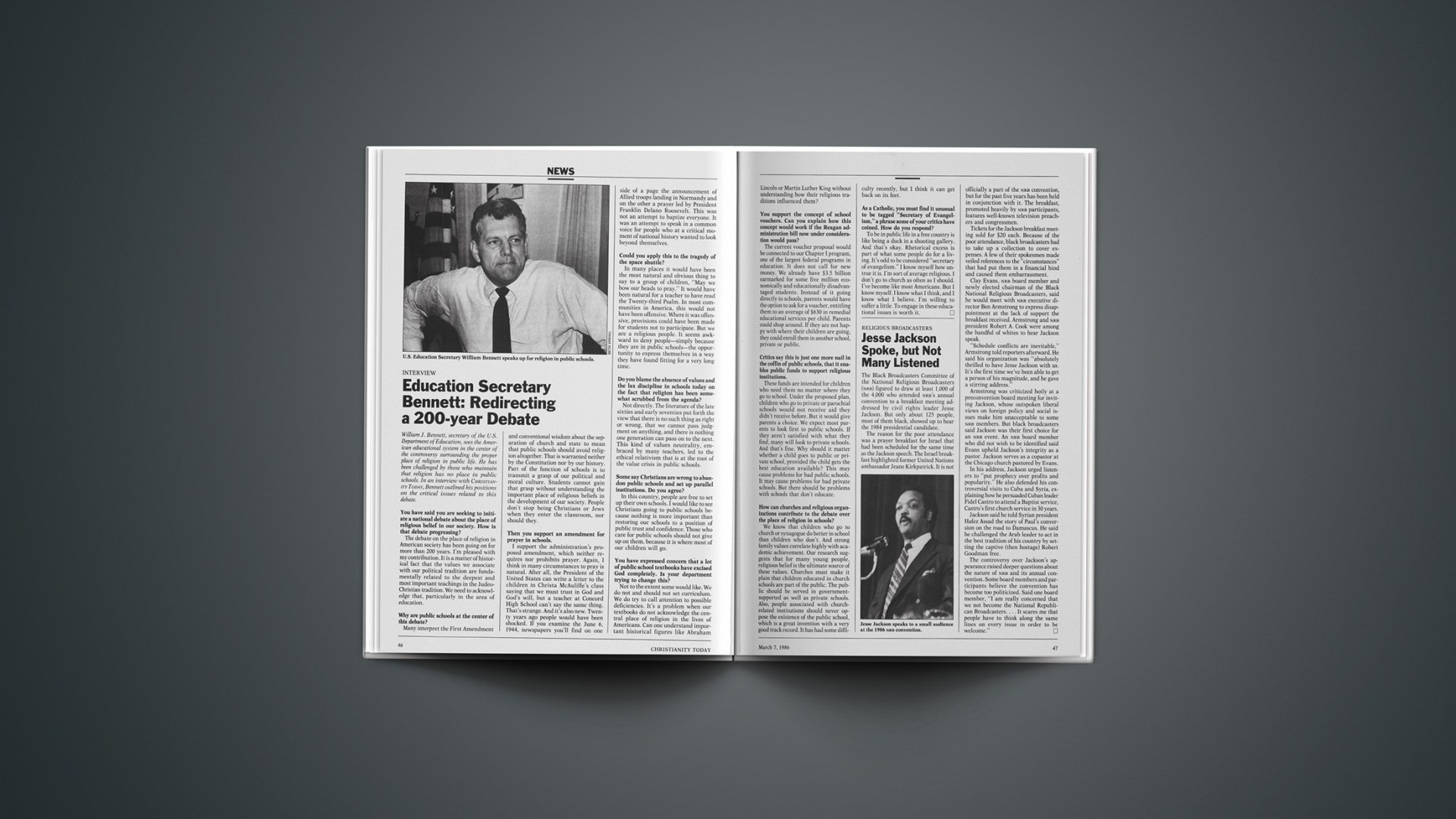

William J. Bennett, secretary of the U.S. Department of Education, sees the American educational system in the center of the controversy surrounding the proper place of religion in public life. He has been challenged by those who maintain that religion has no place in public schools. In an interview with CHRISTIANITY TODAY, Bennett outlined his positions on the critical issues related to this debate.

You have said you are seeking to initiate a national debate about the place of religious belief in our society. How is that debate progressing?

The debate on the place of religion in American society has been going on for more than 200 years. I’m pleased with my contribution. It is a matter of historical fact that the values we associate with our political tradition are fundamentally related to the deepest and most important teachings in the Judeo-Christian tradition. We need to acknowledge that, particularly in the area of education.

Why are public schools at the center of this debate?

Many interpret the First Amendment and conventional wisdom about the separation of church and state to mean that public schools should avoid religion altogether. That is warranted neither by the Constitution nor by our history. Part of the function of schools is to transmit a grasp of our political and moral culture. Students cannot gain that grasp without understanding the important place of religious beliefs in the development of our society. People don’t stop being Christians or Jews when they enter the classroom, nor should they.

Then you support an amendment for prayer in schools.

I support the administration’s proposed amendment, which neither requires nor prohibits prayer. Again, I think in many circumstances to pray is natural. After all, the President of the United States can write a letter to the children in Christa McAuliffe’s class saying that we must trust in God and God’s will, but a teacher at Concord High School can’t say the same thing. That’s strange. And it’s also new. Twenty years ago people would have been shocked. If you examine the June 6, 1944, newspapers you’ll find on one side of a page the announcement of Allied troops landing in Normandy and on the other a prayer led by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt. This was not an attempt to baptize everyone. It was an attempt to speak in a common voice for people who at a critical moment of national history wanted to look beyond themselves.

Could you apply this to the tragedy of the space shuttle?

In many places it would have been the most natural and obvious thing to say to a group of children, “May we bow our heads to pray.” It would have been natural for a teacher to have read the Twenty-third Psalm. In most communities in America, this would not have been offensive. Where it was offensive, provisions could have been made for students not to participate. But we are a religious people. It seems awkward to deny people—simply because they are in public schools—the opportunity to express themselves in a way they have found fitting for a very long time.

Do you blame the absence of values and the lax discipline in schools today on the fact that religion has been somewhat scrubbed from the agenda?

Not directly. The literature of the late sixties and early seventies put forth the view that there is no such thing as right or wrong, that we cannot pass judgment on anything, and there is nothing one generation can pass on to the next. This kind of values neutrality, embraced by many teachers, led to the ethical relativism that is at the root of the value crisis in public schools.

Some say Christians are wrong to abandon public schools and set up parallel institutions. Do you agree?

In this country, people are free to set up their own schools. I would like to see Christians going to public schools because nothing is more important than restoring our schools to a position of public trust and confidence. Those who care for public schools should not give up on them, because it is where most of our children will go.

You have expressed concern that a lot of public school textbooks have excised God completely. Is your department trying to change this?

Not to the extent some would like. We do not and should not set curriculum. We do try to call attention to possible deficiencies. It’s a problem when our textbooks do not acknowledge the central place of religion in the lives of Americans. Can one understand important historical figures like Abraham Lincoln or Martin Luther King without understanding how their religious traditions influenced them?

You support the concept of school vouchers. Can you explain how this concept would work if the Reagan administration bill now under consideration would pass?

The current voucher proposal would be connected to our Chapter I program, one of the largest federal programs in education. It does not call for new money. We already have $3.5 billion earmarked for some five million economically and educationally disadvantaged students. Instead of it going directly to schools, parents would have the option to ask for a voucher, entitling them to an average of $630 in remedial educational services per child. Parents could shop around. If they are not happy with where their children are going, they could enroll them in another school, private or public.

Critics say this is just one more nail in the coffin of public schools, that it enables public funds to support religious institutions.

These funds are intended for children who need them no matter where they go to school. Under the proposed plan, children who go to private or parochial schools would not receive aid they didn’t receive before. But it would give parents a choice. We expect most parents to look first to public schools. If they aren’t satisfied with what they find, many will look to private schools. And that’s fine. Why should it matter whether a child goes to public or private school, provided the child gets the best education available? This may cause problems for bad public schools. It may cause problems for bad private schools. But there should be problems with schools that don’t educate.

How can churches and religious organizations contribute to the debate over the place of religion in schools?

We know that children who go to church or synagogue do better in school than children who don’t. And strong family values correlate highly with academic achievement. Our research suggests that for many young people, religious belief is the ultimate source of these values. Churches must make it plain that children educated in church schools are part of the public. The public should be served in government-supported as well as private schools. Also, people associated with church-related institutions should never oppose the existence of the public school, which is a great invention with a very good track record. It has had some difficulty recently, but I think it can get back on its feet.

As a Catholic, you must find it unusual to be tagged “Secretary of Evangelism,” a phrase some of your critics have coined. How do you respond?

To be in public life in a free country is like being a duck in a shooting gallery. And that’s okay. Rhetorical excess is part of what some people do for a living. It’s odd to be considered “secretary of evangelism.” I know myself how untrue it is. I’m sort of average religious. I don’t go to church as often as I should. I’ve become like most Americans. But I know myself. I know what I think, and I know what I believe. I’m willing to suffer a little. To engage in these educational issues is worth it.