In a recent issue, Newsweek magazine took a deprecatory look at “Rambo Christianity”—fiery fundamentalists who call down wrath on sinners in high places. It seems that when a judge or legislator obstructs the kingdom, certain preachers beseech the Lord to cast down these Babylonian functionaries. To Newsweek, the practice is injudicious and outdated at best: “‘Vengeance is mine,’ says the Lord in the Bible, and some preachers even try to help the process along.… This seems inappropriate for Christian clergy today.”

If the issue were simply that Christians should bless rather than curse, Newsweek would have something. But I suspect the real sticking point is not the prayers of the preachers but the wrath of God. If so, Newsweek’s discomfiture should come as no surprise.

What is surprising is that Christians are equally uneasy with God’s wrath. It is hardly mentioned in our churches and our literature, and that fact ought to concern us. God’s wrath is a central piece in the biblical jigsaw puzzle; if we have made the other pieces fit without it, doesn’t that suggest we have forced them into a pattern God never intended?

A God Without Wrath

Fifty years ago, H. Richard Niebuhr accused the social-gospel movement of misrepresenting the Christian message: “A God without wrath brought men without sin into a kingdom without judgment through the ministrations of a Christ without a Cross.” Theologians had reduced and revised the gospel to make it conform to nineteenth-century optimism. One hopes no evangelical would want to be caught doing that same today.

But once we have given up wrath, can sin, judgment, or the Cross be far behind? Without the one, the others lose their meaning. Wrath measures sin, produces judgment, and necessitates the Cross. Once we have abandoned wrath, the whole Bible becomes unintelligible.

Yet this is what many of us have done. A few months ago, a colleague and I were discussing the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah. She said, “Well, if that’s the way God really is, then I’m not going to believe in him.” That’s strange logic. Yet here we have the quintessential act of rebellion. We make ourselves the final judge, and in that capacity rule all evidence to the contrary inadmissible.

Yet if God is God, his sovereign will wins out even here. The repudiation of the wrath of God is the wrath of God. Running from it means racing toward it. Hiding from it means being found by it. And as the prodigal son discovered, returning to our Father’s strict justice means encountering his infinite mercy. For it is when I say, “I am not worthy to be called your son; make me like one of your hired men,” that God says, “Enter into the joy of your Master.”

As biblical themes go, God’s anger is quite pervasive. We find it in the Old Testament, of course: “This is what the Lord says, ‘Your wound is incurable, your sore beyond healing.… I have struck you as an enemy would and punished you as would the cruel” (Jer. 30:12, 14, NIV). But judgment appears with equal fury in the New Testament: “He will punish those who do not know God and do not obey the gospel of our Lord Jesus. They will be punished with everlasting destruction and shut out from the presence of the Lord and from the majesty of his power” (2 Thess. 1:8–9, NIV).

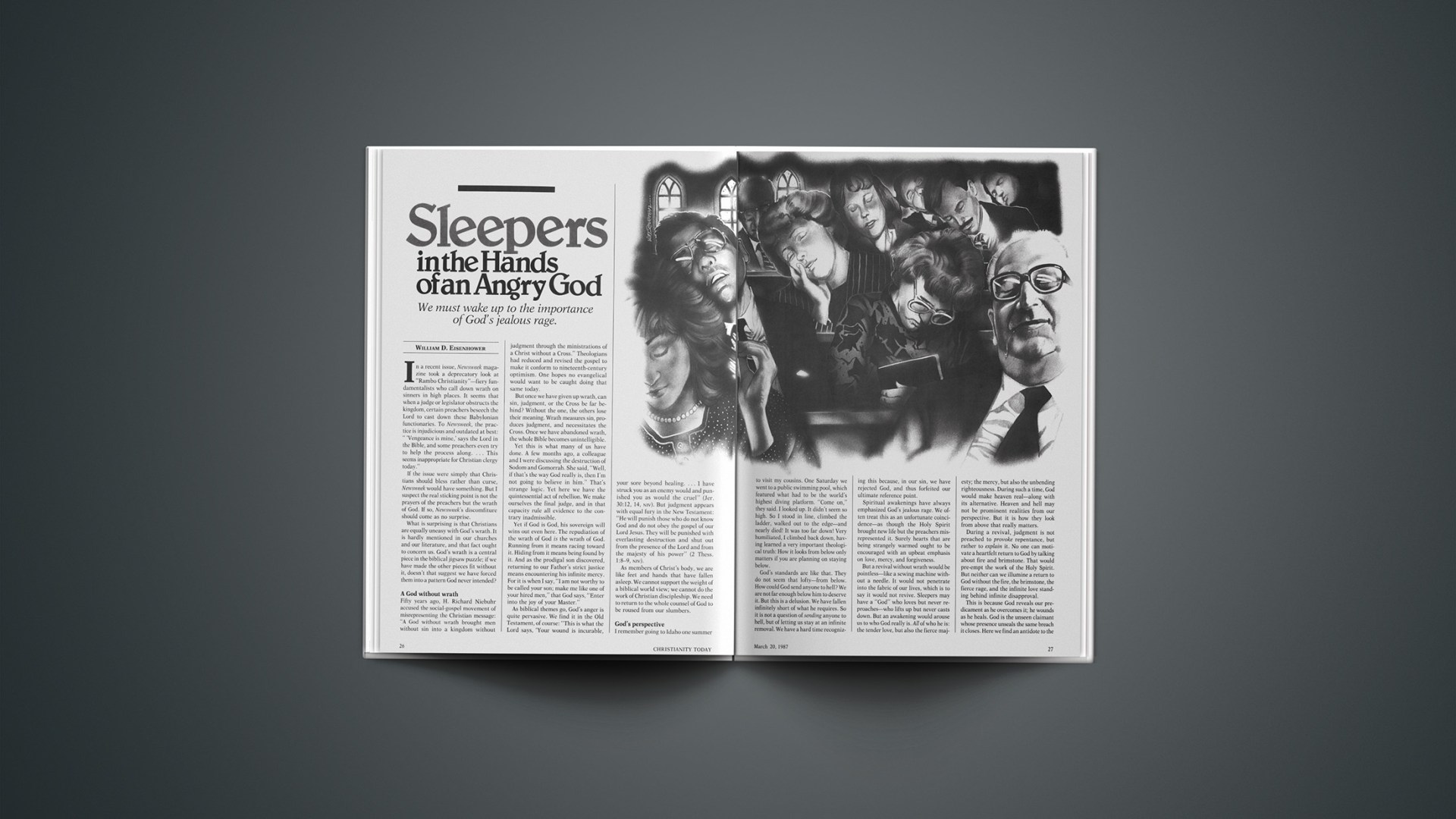

As members of Christ’s body, we are like feet and hands that have fallen asleep. We cannot support the weight of a biblical world view; we cannot do the work of Christian discipleship. We need to return to the whole counsel of God to be roused from our slumbers.

God’s Perspective

I remember going to Idaho one summer to visit my cousins. One Saturday we went to a public swimming pool, which featured what had to be the world’s highest diving platform. “Come on,” they said. I looked up. It didn’t seem so high. So I stood in line, climbed the ladder, walked out to the edge—and nearly died! It was too far down! Very humiliated, I climbed back down, having learned a very important theological truth: How it looks from below only matters if you are planning on staying below.

God’s standards are like that. They do not seem that lofty—from below. How could God send anyone to hell? We are not far enough below him to deserve it. But this is a delusion. We have fallen infinitely short of what he requires. So it is not a question of sending anyone to hell, but of letting us stay at an infinite removal. We have a hard time recognizing this because, in our sin, we have rejected God, and thus forfeited our ultimate reference point.

Spiritual awakenings have always emphasized God’s jealous rage. We often treat this as an unfortunate coincidence—as though the Holy Spirit brought new life but the preachers misrepresented it. Surely hearts that are being strangely warmed ought to be encouraged with an upbeat emphasis on love, mercy, and forgiveness.

But a revival without wrath would be pointless—like a sewing machine without a needle. It would not penetrate into the fabric of our lives, which is to say it would not revive. Sleepers may have a “God” who loves but never reproaches—who lifts up but never casts down. But an awakening would arouse us to who God really is. All of who he is: the tender love, but also the fierce majesty; the mercy, but also the unbending righteousness. During such a time, God would make heaven real—along with its alternative. Heaven and hell may not be prominent realities from our perspective. But it is how they look from above that really matters.

During a revival, judgment is not preached to provoke repentance, but rather to explain it. No one can motivate a heartfelt return to God by talking about fire and brimstone. That would pre-empt the work of the Holy Spirit. But neither can we illumine a return to God without the fire, the brimstone, the fierce rage, and the infinite love standing behind infinite disapproval.

This is because God reveals our predicament as he overcomes it; he wounds as he heals. God is the unseen claimant whose presence unseals the same breach it closes. Here we find an antidote to the modern tendency to think of God as every sinner’s sentimental reassurance: God’s love relieves the terror his anger elicits.

This is why a sense of that anger is a necessary ingredient in spiritual renewal. To wake up in this particular sense means to see that God has come down to save us—not merely from ourselves, or from each other, or from the world. He has reached down in Jesus Christ to save us from himself.

Love Has Conditions

No one has ever liked the idea that God gets angry. But modern believers suffer from confusing notions unique to this century. One of the most pervasive is the concept of “unconditional love”: the idea that God accepts everyone—period—no matter what a person does. This falsehood has to be seen for what it is, a refrain in the lullaby that has put us to sleep. God’s love is not unconditional. It is conditioned by all sorts of things—his integrity, for instance.

Recently I ran across a letter in a Christian periodical. The author was a homosexual seminary student. Its plea went something like this. “God accepts me as I am. I accept myself. Why won’t the church? Why does the church say ‘No’ where God gives an unconditional ‘Yes’?” This student has obviously learned his theology all too well. He is simply asking us to practice what we preach. If we decide we cannot, perhaps we should change our preaching.

Preachers of an earlier era reassured their listeners that the wrath of God was conditioned by his love. It falls to us to assert that the latter is conditioned by the former. Not that the two are equal. The yes governs the no; in Jesus Christ, it overcomes the no. Yet if we fail to give the negative word its due, our “gospel” cannot separate sinners from their sin.

God asks more than that I simply believe I am accepted. He challenges me to repent and believe. If I have not repented, I probably have not started believing, either.

In fact, the church has been able to preach unconditional acceptance only so long as the morality of previous generations has continued its influence. A sense of the wrongness of sin does not die out overnight just because the good sense of some theologians has. For a while, people have continued to be convicted of their sinfulness even though the preachers have stopped arguing that God is offended by it.

But how long can this continue? One generation may not need to hear about God’s wrath, but if it does not, this guarantees that its children surely will. We need the word of the justice, as well as the mercy, of God to put us in touch with our unacknowledged pangs of conscience.

Repentance and Wrath

Many years ago, I was a counselor for a cabin of junior highers. One night, as I lay dead asleep, a dim awareness crept into the shadowy corners of my mind: there were ants crawling all over my body. I didn’t want to wake up; I was too tired to deal with a problem that serious, so I denied it. “You’re only a dream. Please be a dream!” How long I fought the truth, I do not know. Finally, the ants woke me up enough to realize that preferring them away was not going to work. I leaped out of bed, dashed down to the shower house, and washed the little marauders down the drain. After my midnight baptism, I marveled that I had not been bitten once, when I might well have been “eaten alive.”

Grace puts us in a position like that: safe, but shaken to the core. So let’s be blunt. Those who have never returned to God in a panic like my run to the shower house may still be asleep. We put off repenting because we do not like the awful truth that our sin deserves damnation. Jesus Christ was quite serious: “Unless you repent, you too will all perish” (Luke 13:3, NIV).

We try to ignore our apprehensive apprehension of God. But there is no ignoring God, only rejecting his mercy, which means sleeping in his vengeance. We have been making our beds in Sheol. No one wants to wake up and face that. But God in his mercy stirs some. Suppose, however, that we teach these newly roused believers that God loves them, forgives them, and has nothing but positive regard for them—period. They have not heard about wrath. We have not helped them locate the corners of their hearts that still resist the advance of grace. And that is precisely what they need: help in understanding their predicament so they can appreciate the offer they are in the process of receiving.

Time to Wake Up!

As a Presbyterian, I have to confess our mainline denominations went to sleep a generation ago. At the time, we were strong and confident—perhaps overconfident. We awaken now rather like Samson, our former strength cut short. According to theologian Thomas Oden, the church has never seen a generation to match this one for beginning with so much and ending with so little. In fact, we have been dozing for so long that Rip Van Winkle ties with Samson as the most fitting analogue. We awaken to a world drastically changed: liberty eroded, morality dethroned, decency repudiated, common sense ignored, minds glazed over, hearts hardened. And worst of all, our doctrine of God is precisely that: ours.

We can believe in a “God” acceptable to culture, a “God” of all-accepting, morally indifferent, unconditional love, or we can repent and believe in the God of the Old and New Testaments. But we cannot do both. They are incompatible. It is time to awaken, to strengthen what remains, and to reopen our eyes to what the Bible actually says.

We are like servants left in charge of our master’s house. We ought to render our service faithfully and fearfully as though each day were our last. For suppose it is? “Do not let him find you sleeping” (Mark 13:36).

William Eisenhower is pastor of First Presbyterian Church in Hollister, California. He holds the Ph.D. from Union Theological Seminary in Virginia, and has written for Christianity Today and The Wittenburg Door.