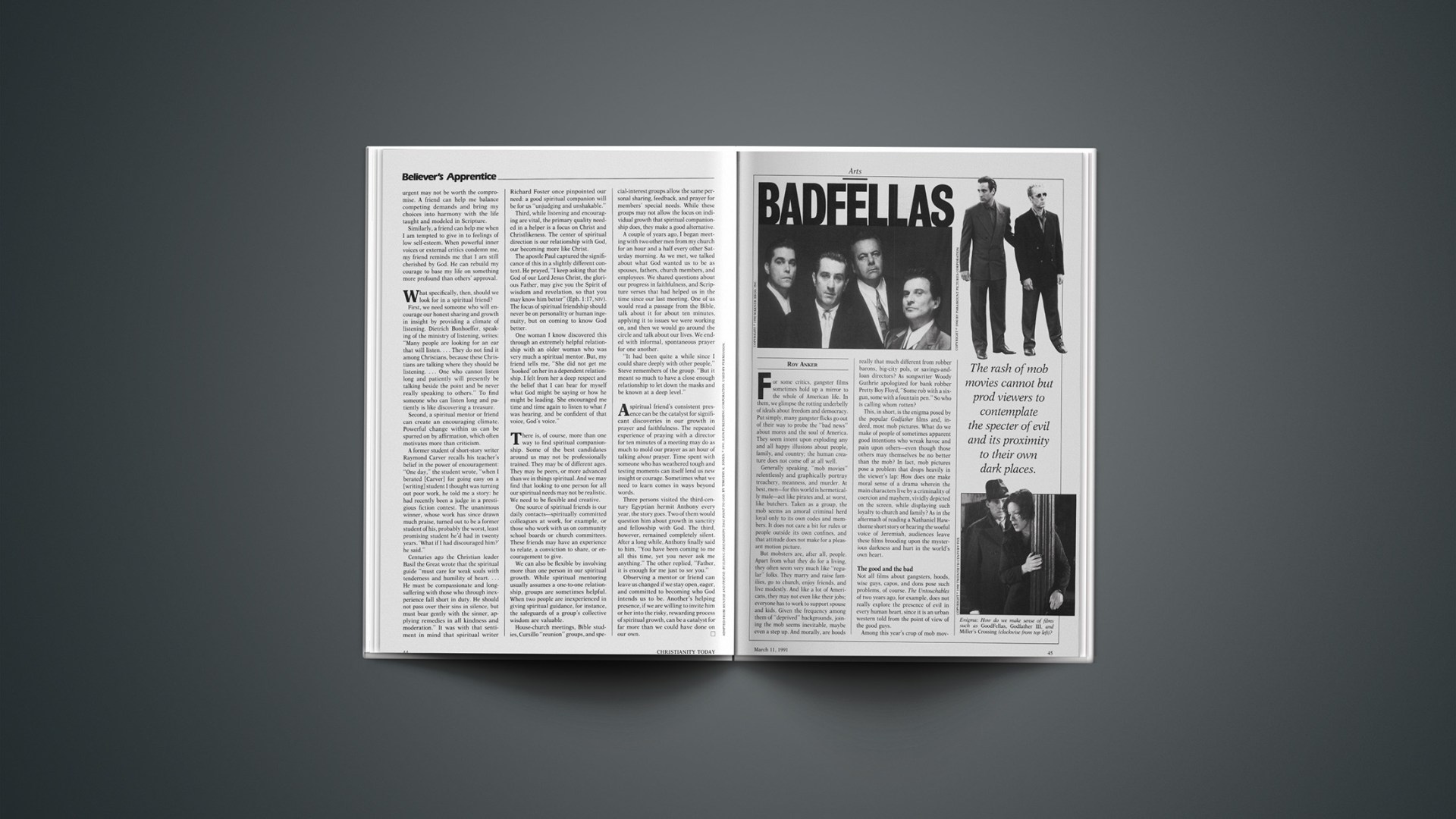

For some critics, gangster films sometimes hold up a mirror to the whole of American life. In them, we glimpse the rotting underbelly of ideals about freedom and democracy. Put simply, many gangster flicks go out of their way to probe the “bad news” about mores and the soul of America. They seem intent upon exploding any and all happy illusions about people, family, and country; the human creature does not come off at all well.

Generally speaking, “mob movies” relentlessly and graphically portray treachery, meanness, and murder. At best, men—for this world is hermetically male—act like pirates and, at worst, like butchers. Taken as a group, the mob seems an amoral criminal herd loyal only to its own codes and members. It does not care a bit for rules or people outside its own confines, and that attitude does not make for a pleasant motion picture.

But mobsters are, after all, people. Apart from what they do for a living, they often seem very much like “regular” folks. They marry and raise families, go to church, enjoy friends, and live modestly. And like a lot of Americans, they may not even like their jobs; everyone has to work to support spouse and kids. Given the frequency among them of “deprived” backgrounds, joining the mob seems inevitable, maybe even a step up. And morally, are hoods really that much different from robber barons, big-city pols, or savings-and-loan directors? As songwriter Woody Guthrie apologized for bank robber Pretty Boy Floyd, “Some rob with a six-gun, some with a fountain pen.” So who is calling whom rotten?

This, in short, is the enigma posed by the popular Godfather films and, indeed, most mob pictures. What do we make of people of sometimes apparent good intentions who wreak havoc and pain upon others—even though those others may themselves be no better than the mob? In fact, mob pictures pose a problem that drops heavily in the viewer’s lap: How does one make moral sense of a drama wherein the main characters live by a criminality of coercion and mayhem, vividly depicted on the screen, while displaying such loyalty to church and family? As in the aftermath of reading a Nathaniel Hawthorne short story or hearing the woeful voice of Jeremiah, audiences leave these films brooding upon the mysterious darkness and hurt in the world’s own heart.

The Good And The Bad

Not all films about gangsters, hoods, wise guys, capos, and dons pose such problems, of course. The Untouchables of two years ago, for example, does not really explore the presence of evil in every human heart, since it is an urban western told from the point of view of the good guys.

Among this year’s crop of mob movies inspired by the profitability of The Untouchables, one—the arty Miller’s Crossing—is plainly incoherent. It is neither interesting, plausible, nor intelligible.

Of greater interest is Phillip Janou’s State of Grace, which is a better picture than most critics allowed. A young Irish cop (Sean Penn) returns to New York’s Hell’s Kitchen to work undercover in an effort to infiltrate an upstart Irish mob. Before long, he must struggle with affection for his youthful friends (and girlfriend) and the call of duty. It is a rough and grim picture that delivers less hope than it promises in its title. Its moral conflict resides in a single character; rather than struggling with the issues itself, the audience merely observes the hero struggle.

One mob picture has won almost universal acclaim. Martin Scorsese’s Good-Fellas is adapted from Wiseguy, Michael Peglisi’s best-selling account of the life of New York mobster Henry Hill. With Hill (Ray Liotta) narrating, the film, in rather neutral fashion—if the camera is ever neutral—traces Hill’s career in the mob from his years as a willing teenage errand boy to his midlife decision to turn “stool pigeon” and enter a witness-protection program.

It is a chilling tale. Director Scorsese is not out to turn mob life into opera, tragic epic, or morality play, as the Godfather saga is sometimes accused of doing. Instead, he tries to get inside the “skin” (and soul, perhaps), unsanitized and unromanticized, of the ordinary mob “soldier” in order to convey daily life in the mob. By such close scrutiny, audiences can perhaps derive some sense of what drives, beckons, and haunts the bad guys. Scorsese shows life in the mob from the point of view of the mob. For those of us who possess a “normal” moral sense, it is a quick trip through a very unpretty section of hell.

For young Henry Hill, who is a “gofer” for the mob guys who hang out across the street, there is the euphoria of “respect” and power that comes with associating with them. And it sure beats school. Later will come money, women, and privilege. For Hill, freedom means being above, and beyond, the cares and woes of ordinary people. It is an addictive liberty. Throughout, there is the buoyant camaraderie of the “family”—warm and certain, but dangerous if violated. It looks good, and it feels better. What could be more easy, natural, and “right”? After all, we all want to be somebody. The high life of privilege seems well worth its constant scramble for survival and its high moral price—if such questions ever occur to Hill and his compatriots.

It is the seductive frenzy of the daily scramble that finally catches up to Hill when his desires outstrip his finances, and when the feds catch him free-lancing drugs—also a crime in the mob. To beat prison and mob vengeance, he testifies and takes on a new identity. The last scene shows Hill, with his bankroll and fresh start, in his new, but drab tract house complaining that he is now “a poor schnook who has to wait around like everyone else.” Some people never learn.

Given its premises, Hill’s world is, in its own way, entirely plausible, and it seems neither corrupt nor even silly. Murders, drugs, and mistresses all have their place—within, of course, a certain point of view. In short, with more than ample illustration, Scorsese gradually drops the inescapable mystery of iniquity smack in the viewer’s lap and lets it take the soul by surprise.

Of God And Godfather

Of major importance, of course, is the three-part Godfather saga, which chronicles three generations in the life of the Corleone crime family. Taken together, or even individually, these films make a remarkable document whose profound moral insight matches its startling artistic accomplishment. There are few imaginative works like it, either in cinema or in literature.

The first film, in 1972, took the critics and the country alike by storm. Only two years later, the sequel surpassed the first in acclaim—a rarity, to be sure—although box office fell off a bit. Now, some 16 years later, in the third installment, director Francis Ford Coppola and screenwriter Mario Puzo (whose best-selling novel inspired the series) again lay out a harrowing tale of deceit, violence, and moral darkness. Yet they manage to inject a new, surprising, and cogent element: one man’s desperate quest for moral and spiritual redemption.

In the first film, Coppola dramatized the succession of power from aging Vito Corleone (Marlon Brando) to his sons. The heir apparent, hot-tempered Sonny (James Caan), is assassinated amid gang warfare. Second son Fredo (John Cazale) is not up to leadership. The mantle then falls, partly by necessity and partly by choice, to youngest son Michael (Al Pacino), the son Vito had raised to find conventional respectability in American society. Indeed, the idealistic Michael indicates his own distance from his clan when he tells his blond, WASP girlfriend Kaye (Diane Keaton) that the family is “not me.” Still, inexorably, events entangle Michael in the dark demands of family survival, the protection of women and children for which men in this particular world are responsible. Who can doubt the good of that high goal?

It is easy to sympathize with and even apologize for Michael. For a time, his actions in The Godfather seem heroic. Bright, moderate, and courageous, Michael does only what mayhem is necessary, however unpleasant it might be. Still, where he ends up in this him is ample cause for fright, for his destination represents a decay not only of his own person but also of his father’s ethical standards. As the movie takes pains to show, Don Vito Corleone lives by sober realism, and from within that somber analysis of the way the world works, he tries to take care of his family and those loyal to him. He uses no more force than is necessary to bring results; he is thoughtful, deliberate, just, kindly, and restrained—in short, a man who hates violence even as he uses it. Indeed, in Coppola’s fallen world, the don looks like a paragon of wisdom and virtue. In contrast, those who oppose him are more violent, corrupt, and ruthless, whether they be mob rivals, movie producers, policemen, or singers.

By the end of the first film, the multiple tragedies of death and betrayal drive Michael to a paranoia that devours his lingering moral idealism. In one of the great sequences in American movies, Coppola dramatizes Michael’s moral collapse. While he stands godfather to his nephew, sacramentally renouncing Satan and all his “pomps,” his henchmen undertake retributive assassination of all rivals. In deceit, murder, and apostasy, Michael himself has become the Prince of Darkness. The shaken audience is left to ponder the means by which evil conquers goodness.

The Godfather Part II (1974) goes both backward and forward as Coppola again focuses on the moral histories of father and son. We pick up Michael’s story in 1959 as he moves to Nevada in an effort to legitimize the family’s financial holdings. Caught ever deeper in a web of intrigue and violent power-mongering, his capacity for betrayal deepens until finally he is himself renounced by all—brother, wife, and children. In his attempt to save his family, he loses it. Now somewhat respectable, he becomes a moral monster whose desolation is almost beyond grasp.

To accentuate this hideous moral collapse, Coppola mixes Michael’s story with the early life of his father, Vito, an orphan exile of Sicilian Mafia violence. As a young father in New York, Vito (Robert De Niro) loses his job to the local don’s nephew. Rather than be a “puppet” who sacrifices his family to his own weakness, he fights back in the only way available. Vito thus enters a world of pervasive moral ambiguity: revering his family and willing to do anything to preserve it. Here are the makings of a comparatively “humane” godfather, one who has suffered from violence and coercion, who reckons the cost of living in the real world. As young Vito ascends, young Michael descends.

This season’s Godfather, set 20 years later, focuses on an aging and tortured Michael. Immensely rich, at last respectable, and seeking to extricate the family from illegality, he gives the Roman Catholic Church $100 million for the restoration of Sicily. With the Vatican’s assistance, he hopes to buy into an international conglomerate, only to find out that it, too, is mob controlled. Moreover, he falls prey to the machinations of a corrupt Vatican bank.

But these vexations pale alongside Michael’s agony of guilt, a torture for which he believes there is no help. Pacino is brilliant in his characterization of a man who has gained the world but lost his soul in murder and betrayal. When he goes to Sicily for his son’s operatic debut, he tells his ex-wife that he dreams every night of how he “lost” his wife and family. His suffering is written in his face and shows in his failing health. He confesses crimes, but without repenting, to a cardinal who tells him it is right that he suffers.

Absolution seems to come at last when, at the coffin of a friend, Michael ponders his own deep, lifelong error of mind and heart. Though shrewd and loyal, he nonetheless lacked love and thereby destroyed all who came near him. Struggling to change his ways, he risks the Devil’s game once too often. The fate of his quest for forgiveness lies in the dust of Sicily, the place from which his father fled.

It is the specter of Michael Corleone’s spiritual agony that properly hounds audiences to search their souls for their own share in—to use Hawthorne’s phrase—“the universal bloodspot.”

Humanity’s Dark Side Personified

The mob pictures by Scorsese and Coppola graphically dramatize the way metaphysical evil takes tangible human form. (These movies are not tame, and suitable only for adults with strong stomachs.) The stories are told in emphatic ways that must inevitably prod us as viewers to contemplate not only the specter of evil, but also its proximity to the dark places in our own lives. Henry Hill, after all, works hard and is only having fun. He is full of high jinks and affection for his coworkers; it all seems perfectly reasonable.

As for Vito and Michael Corleone, through most of their lives they believe they are doing righteousness within their—and our—tangled world. What will it take, for them or us, to make us ponder, like Michael, the wrongness of mind and heart? And how do we come to love?

Because they pose these hard questions with inescapable directness, we must thank God for the power of art and for filmmakers who hold up the mirror that reflects in a graphic way our own souls.