Homosexuals at Christian colleges press for acceptance.

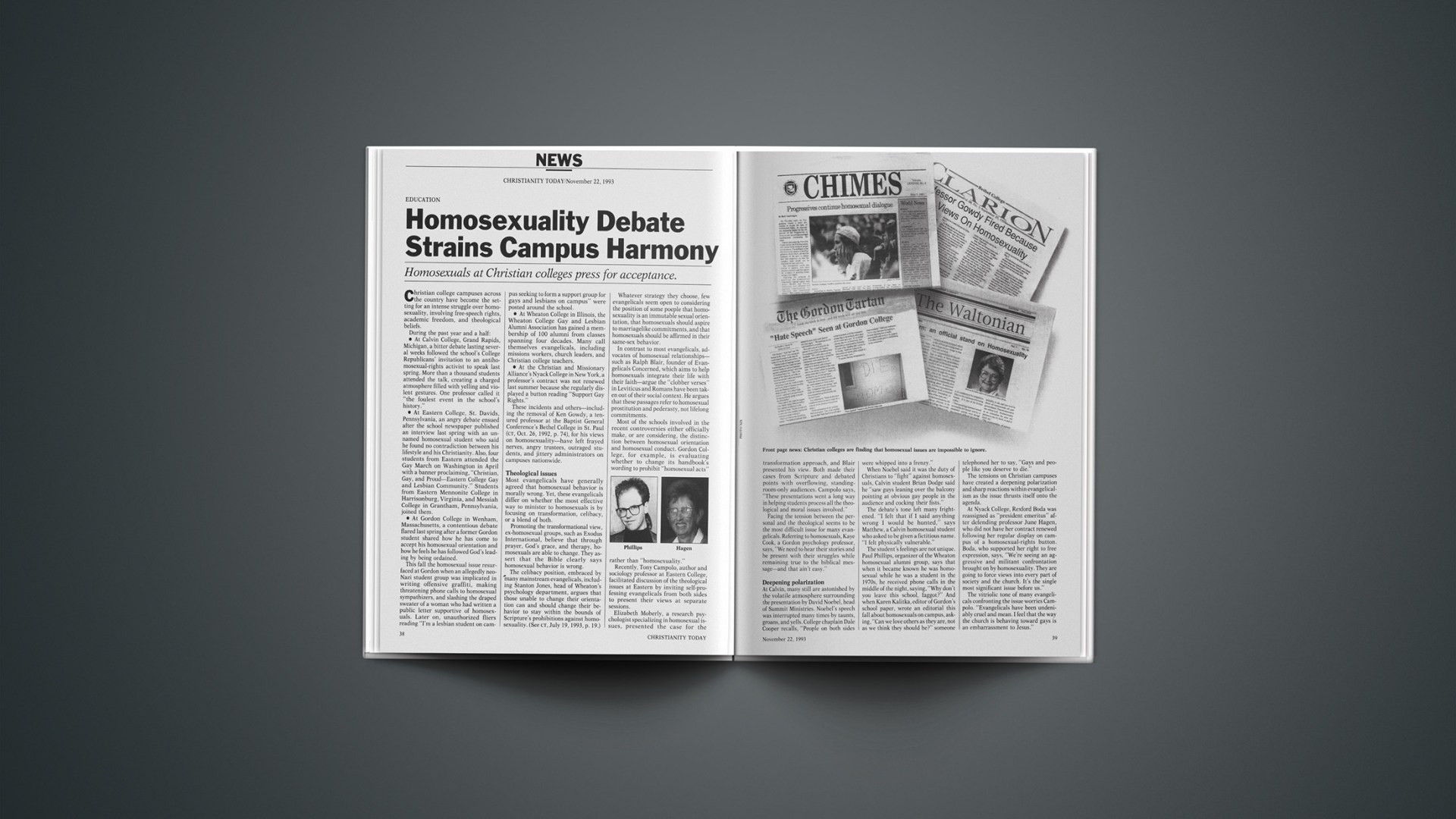

Christian college campuses across the country have become the setting for an intense struggle over homosexuality, involving free-speech rights, academic freedom, and theological beliefs.

During the past year and a half:

• At Calvin College, Grand Rapids, Michigan, a bitter debate lasting several weeks followed the school’s College Republicans’ invitation to an antihomosexual-rights activist to speak last spring. More than a thousand students attended the talk, creating a charged atmosphere filled with yelling and violent gestures. One professor called it “the foulest event in the school’s history.”

• At Eastern College, St. Davids, Pennsylvania, an angry debate ensued after the school newspaper published an interview last spring with an unnamed homosexual student who said he found no contradiction between his lifestyle and his Christianity. Also, four students from Eastern attended the Gay March on Washington in April with a banner proclaiming, “Christian, Gay, and Proud—Eastern College Gay and Lesbian Community.” Students from Eastern Mennonite College in Harrisonburg, Virginia, and Messiah College in Grantham, Pennsylvania, joined them.

• At Gordon College in Wenham, Massachusetts, a contentious debate flared last spring after a former Gordon student shared how he has come to accept his homosexual orientation and how he feels he has followed God’s leading by being ordained.

This fall the homosexual issue resurfaced at Gordon when an allegedly neo-Nazi student group was implicated in writing offensive graffiti, making threatening phone calls to homosexual sympathizers, and slashing the draped sweater of a woman who had written a public letter supportive of homosexuals. Later on, unauthorized fliers reading “I’m a lesbian student on campus seeking to form a support group for gays and lesbians on campus” were posted around the school.

• At Wheaton College in Illinois, the Wheaton College Gay and Lesbian Alumni Association has gained a membership of 100 alumni from classes spanning four decades. Many call themselves evangelicals, including missions workers, church leaders, and Christian college teachers.

• At the Christian and Missionary Alliance’s Nyack College in New York, a professor’s contract was not renewed last summer because she regularly displayed a button reading “Support Gay Rights.”

These incidents and others—including the removal of Ken Gowdy, a tenured professor at the Baptist General Conference’s Bethel College in St. Paul (CT, Oct. 26, 1992, p. 74), for his views on homosexuality—have left frayed nerves, angry trustees, outraged students, and jittery administrators on campuses nationwide.

Theological issues

Most evangelicals have generally agreed that homosexual behavior is morally wrong. Yet, these evangelicals differ on whether the most effective way to minister to homosexuals is by focusing on transformation, celibacy, or a blend of both.

Promoting the transformational view, ex-homosexual groups, such as Exodus International, believe that through prayer, God’s grace, and therapy, homosexuals are able to change. They assert that the Bible clearly says homosexual behavior is wrong.

The celibacy position, embraced by many mainstream evangelicals, including Stanton Jones, head of Wheaton’s psychology department, argues that those unable to change their orientation can and should change their behavior to stay within the bounds of Scripture’s prohibitions against homosexuality. (See CT, July 19, 1993, p. 19.)

Whatever strategy they choose, few evangelicals seem open to considering the position of some poeple that homosexuality is an immutable sexual orientation, that homosexuals should aspire to marriagelike commitments, and that homosexuals should be affirmed in their same-sex behavior.

In contrast to most evangelicals, advocates of homosexual relationships—such as Ralph Blair, founder of Evangelicals Concerned, which aims to help homosexuals integrate their life with their faith—argue the “clobber verses” in Leviticus and Romans have been taken out of their social context. He argues that these passages refer to homosexual prostitution and pederasty, not lifelong commitments.

Most of the schools involved in the recent controversies either officially make, or are considering, the distinction between homosexual orientation and homosexual conduct. Gordon College, for example, is evaluating whether to change its handbook’s wording to prohibit “homosexual acts” rather than “homosexuality.”

Recently, Tony Campolo, author and sociology professor at Eastern College, facilitated discussion of the theological issues at Eastern by inviting self-professing evangelicals from both sides to present their views at separate sessions.

Elizabeth Moberly, a research psychologist specializing in homosexual issues, presented the case for the transformation approach, and Blair presented his view. Both made their cases from Scripture and debated points with overflowing, standing-room-only audiences. Campolo says, “These presentations went a long way in helping students process all the theological and moral issues involved.”

Facing the tension between the personal and the theological seems to be the most difficult issue for many evangelicals. Referring to homosexuals, Kaye Cook, a Gordon psychology professor, says, “We need to hear their stories and be present with their struggles while remaining true to the biblical message—and that ain’t easy.”

Deepening polarization

At Calvin, many still are astonished by the volatile atmosphere surrounding the presentation by David Noebel, head of Summit Ministries. Noebel’s speech was interrupted many times by taunts, groans, and yells. College chaplain Dale Cooper recalls, “People on both sides were whipped into a frenzy.”

When Noebel said it was the duty of Christians to “fight” against homosexuals, Calvin student Brian Dodge said he “saw guys leaning over the balcony pointing at obvious gay people in the audience and cocking their fists.”

The debate’s tone left many frightened. “I felt that if I said anything wrong I would be hunted,” says Matthew, a Calvin homosexual student who asked to be given a fictitious name. “I felt physically vulnerable.”

The student’s feelings are not unique. Paul Phillips, organizer of the Wheaton homosexual alumni group, says that when it became known he was homosexual while he was a student in the 1970s, he received phone calls in the middle of the night, saying, “Why don’t you leave this school, faggot?” And when Karen Kalitka, editor of Gordon’s school paper, wrote an editorial this fall about homosexuals on campus, asking, “Can we love others as they are, not as we think they should be?” someone telephoned her to say, “Gays and people like you deserve to die.”

The tensions on Christian campuses have created a deepening polarization and sharp reactions within evangelicalism as the issue thrusts itself onto the agenda.

At Nyack College, Rexford Boda was reassigned as “president emeritus” after defending professor June Hagen, who did not have her contract renewed following her regular display on campus of a homosexual-rights button. Boda, who supported her right to free expression, says, “We’re seeing an aggressive and militant confrontation brought on by homosexuality. They are going to force views into every part of society and the church. It’s the single most significant issue before us.”

The vitriolic tone of many evangelicals confronting the issue worries Campolo. “Evangelicals have been undeniably cruel and mean. I feel that the way the church is behaving toward gays is an embarrassment to Jesus.”

Freedom to debate

Nevertheless, school administrators assert persistently that while they believe the Bible says homosexual sex is wrong, they are determined to foster a more civil and loving discourse. Jeanette De-Jong, vice president for student affairs at Calvin, says, “We did not struggle with David Noebel’s content, but with the style of the presentation. It lacked a measure of grace.”

At Eastern College, president Roberta Hestenes declared discrimination against homosexuals would not be tolerated and would be treated the same way racial slurs are treated.

And at Gordon, after the appearance of graffiti on a classroom door that said, “Die Homos,” the administration announced that hate speech would be disciplined.

These stands as well as the large number of students who wrote letters to their school newspapers condemning the bitterness of the debate seems to have reassured some homosexuals that it might be safe for them to remain enrolled at Christian colleges. Matthew went back to Calvin this fall, and Alan Speer, a homosexual Calvin student who graduated last spring, says he left with no ill will. “I’m kind of glad it happened, because it brought the issue out of the closet.”

One of the most worrisome aspects of faculty terminations has been the issue of academic freedom. One Christian college professor, who wished to remain anonymous, says, “It shuts down dialogue and puts a cloud over the entire faculty, where we begin to be unsure of what we can or cannot say and what might be grounds for dismissal.”

Former Nyack professor Hagen says adamantly, “I believe it is my duty as an educator to help the institutions I serve to grapple with ideas, including controversial ones.”

Faculty terminations raise the important question: What is the goal of a Christian liberal arts school? Psychologist Cook says, “The calling of a Christian liberal arts college is to address controversial issues to help students see their complexity and help them articulate a biblical position.”

Richard Gathro, vice president of the Christian College Coalition, believes the key to academic freedom is for Christian schools to have internal consistency between what they believe and what they practice. “This is why Bethel said, in the Gowdy case, ‘We can’t have someone advocating something contrary to the teachings of our denomination.’ ”

But Gathro does worry, with accrediting associations becoming more politically active and some states passing homosexual-rights legislation, that some Christian schools might become vulnerable to losing accreditation or to lawsuits.

When A Student Comes Out

The auditorium hall was packed, the atmosphere tense. For several weeks the debate raged regarding a series of articles in the campus newspaper, including an interview with an unnamed homosexual student.

During the meeting on the issue, Eastern College president Roberta Hestenes said discrimination against homosexuals would not be tolerated, but at the same time, she reaffirmed the school’s position that homosexual acts are wrong. Then a hand went up in the middle of the room, and Hestenes called on the person. Don Dyson, a well-known student, stood up. “You need to know that the person you’re all talking about who did the interview is me.”

In most people’s minds, it could not have been a more unlikely person. Dyson was an editor at the school paper, on the homecoming court, lead actor in the school’s major plays, and a top academic student known for his strong Christian convictions.

After the assembly, several students approached Dyson with comments ranging from wholehearted support to condemnation. Dyson’s coming out of the closet changed the tenor of the debate. “For your sake, we gays and lesbians have to tell you who we are,” Dyson told his fellow students. “Accept us or reject us as real people.” Dyson graduated last spring and last month made marriagelike vows to an Eastern College graduate he met in the school’s production of Godspell.

Yet, Alexis Crow, legal coordinator at the Rutherford Institute, the religious-rights organization, says, “A Christian school, because it is a private institution, has the right to stand up for a theological conviction.”

Evangelical and homosexual?

The coming out of homosexuals who say they remain true to their evangelical heritage is galvanizing the schools’ theological debate. These students often are respected by their peers and teachers, and their faith language is familiar.

Yet many homosexuals on Christian campuses remain in the closet for fear of rejection by their closest friends and expulsion from school, or because they are still working through the issues.

Administrators, however, are unyielding in policies that declare homosexual behavior unbiblical and those who violate the code of conduct will be disciplined. DeJong at Calvin says, “We expect students who are gay or lesbian to honor the standards of biblical sexuality, which does not allow homosexual behavior.”

Blair argues that if homosexual students on Christian campuses do not find support, they will go outside the school to find it. “If gay students can’t date on campus, where are they going to find someone to share their life with?” he asks. “Despair sends them out to the wolves.”

Wheaton alumnus Phillips says he started the Wheaton College Gay and Lesbian Alumni Association when he heard that a student “struggling with his sexual orientation committed suicide.” He hopes to convince the Wheaton administration to refer homosexual students to the group. The school, however, is unlikely to do so because of concern that these students would simply find encouragement to stay in the homosexual lifestyle.

The prohibition on homosexual conduct creates the practical problem of specifically defining such behavior. Campolo says, “We get in the awkward position of saying it is okay for one group of women to put arms around each other, but not okay for another.”

Despite firm administrative stands, more homosexuals at Christian colleges are testing the limits, forcing their campus communities to confront the divisive issue of homosexuality. Because they are often respected, likable, and spiritually committed students, the issue moves from being solely a political and moral debate to being an agonizingly personal one.

By Andres Tapia.