Cedar Duaybis, a grandmother of five, al ways swore that she would never flee again. In 1948, when Duaybis was a child, her Palestinian Christian family fled the Mediterranean city of Haifa amid fighting between Arab forces and the newly declared state of Israel, winding up as refugees in the West Bank city of Ramallah.

But recently Duaybis fled again as Israeli helicopter gunships were poised to attack the Ramallah headquarters of Palestinian President Yasser Arafat, just 100 yards from her home. Before this reprisal for the Palestinian killing of two Israeli reserve soldiers began, she grabbed her granddaughter and a number of her friends and ran to Ramallah’s Anglican Church compound to spend the night.

“The thing I think about most is the children,” said Duaybis, the widow of an Anglican priest.

“I remember how I was so scared and frightened in 1948, and no adult had time to explain what was going on. Now I have a grandchild, and she is going through the same thing.”

The West Bank’s tiny Palestinian Christian community of 45,000 people, including avid proponents of the peace process, has become deeply embroiled in the current disturbances, which are striking dangerously close to home. Most of the West Bank’s Christians are concentrated in Ramallah, Arab east Jerusalem, and the Bethlehem district—flash points in the current unrest.

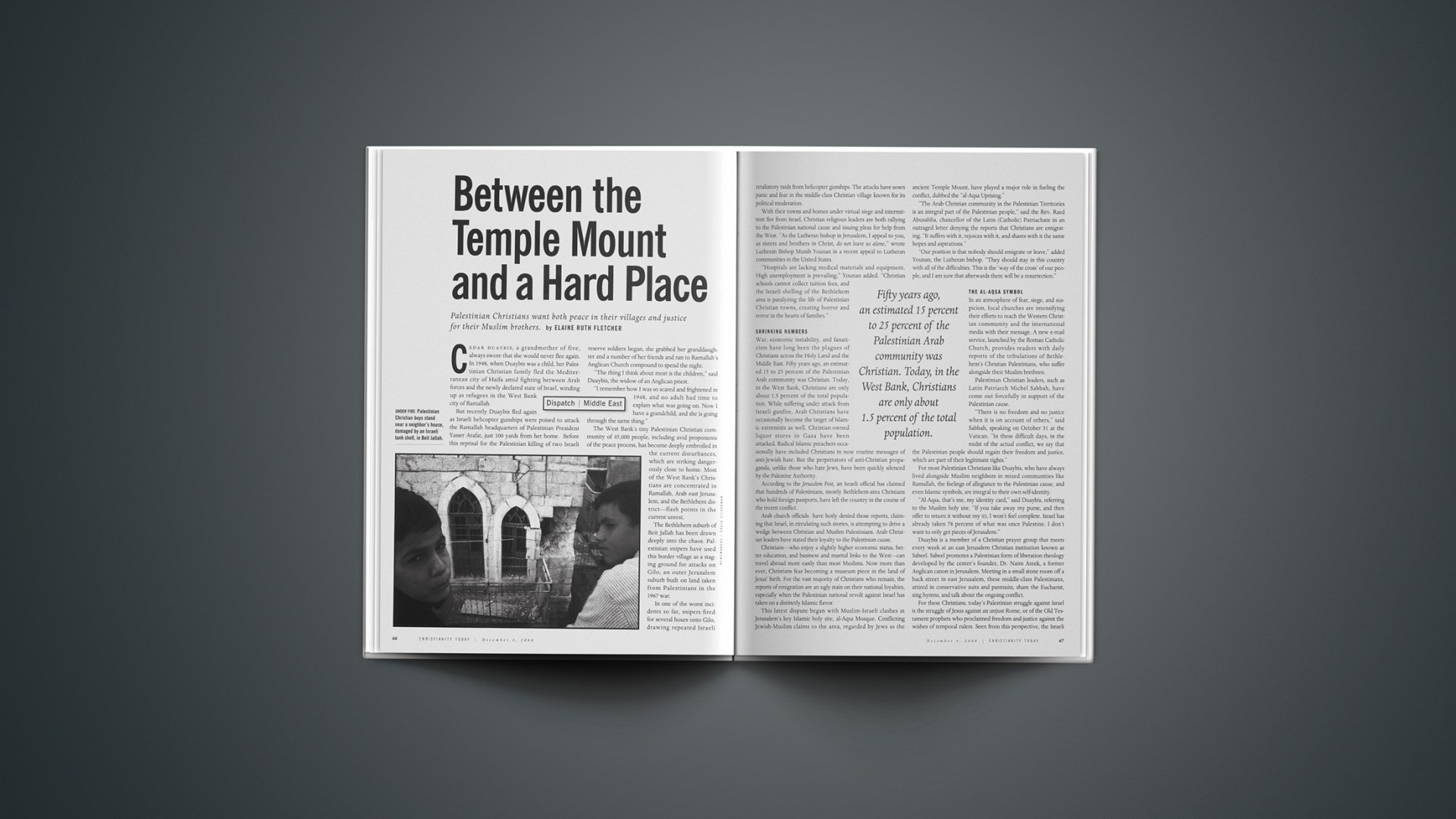

The Bethlehem suburb of Beit Jallah has been drawn deeply into the chaos. Palestinian snipers have used this border village as a staging ground for attacks on Gilo, an outer Jerusalem suburb built on land taken from Palestinians in the 1967 war.

In one of the worst incidents so far, snipers fired for several hours onto Gilo, drawing repeated Israeli retaliatory raids from helicopter gunships. The attacks have sown panic and fear in the middle-class Christian village known for its political moderation.

With their towns and homes under virtual siege and intermittent fire from Israel, Christian religious leaders are both rallying to the Palestinian national cause and issuing pleas for help from the West. “As the Lutheran bishop in Jerusalem, I appeal to you, as sisters and brothers in Christ, do not leave us alone,” wrote Lutheran Bishop Munib Younan in a recent appeal to Lutheran communities in the United States.

“Hospitals are lacking medical materials and equipment. High unemployment is prevailing,” Younan added. “Christian schools cannot collect tuition fees, and the Israeli shelling of the Bethlehem area is paralyzing the life of Palestinian Christian towns, creating horror and terror in the hearts of families.”

Shrinking numbers

War, economic instability, and fanaticism have long been the plagues of Christians across the Holy Land and the Middle East. Fifty years ago, an estimated 15 to 25 percent of the Palestinian Arab community was Christian. Today, in the West Bank, Christians are only about 1.5 percent of the total population. While suffering under attack from Israeli gunfire, Arab Christians have occasionally become the target of Islamic extremists as well. Christian-owned liquor stores in Gaza have been attacked. Radical Islamic preachers occasionally have included Christians in now routine messages of anti-Jewish hate. But the perpetrators of anti-Christian propaganda, unlike those who hate Jews, have been quickly silenced by the Palestine Authority.

According to the Jerusalem Post, an Israeli official has claimed that hundreds of Palestinians, mostly Bethlehem-area Christians who hold foreign passports, have left the country in the course of the recent conflict.

Arab church officials have hotly denied those reports, claiming that Israel, in circulating such stories, is attempting to drive a wedge between Christian and Muslim Palestinians. Arab Christian leaders have stated their loyalty to the Palestinian cause.

Christians—who enjoy a slightly higher economic status, better education, and business and marital links to the West—can travel abroad more easily than most Muslims. Now more than ever, Christians fear becoming a museum piece in the land of Jesus’ birth. For the vast majority of Christians who remain, the reports of emigration are an ugly stain on their national loyalties, especially when the Palestinian national revolt against Israel has taken on a distinctly Islamic flavor.

This latest dispute began with Muslim-Israeli clashes at Jerusalem’s key Islamic holy site, al-Aqsa Mosque. Conflicting Jewish-Muslim claims to the area, regarded by Jews as the ancient Temple Mount, have played a major role in fueling the conflict, dubbed the “al-Aqsa Uprising.”

“The Arab Christian community in the Palestinian Territories is an integral part of the Palestinian people,” said the Rev. Raed Abusahlia, chancellor of the Latin (Catholic) Patriachate in an outraged letter denying the reports that Christians are emigrating. “It suffers with it, rejoices with it, and shares with it the same hopes and aspirations.”

“Our position is that nobody should emigrate or leave,” added Younan, the Lutheran bishop. “They should stay in this country with all of the difficulties. This is the ‘way of the cross’ of our people, and I am sure that afterwards there will be a resurrection.”

The al-Aqsa symbol

In an atmosphere of fear, siege, and suspicion, local churches are intensifying their efforts to reach the Western Christian community and the international media with their message. A new e-mail service, launched by the Roman Catholic Church, provides readers with daily reports of the tribulations of Bethlehem’s Christian Palestinians, who suffer alongside their Muslim brethren.

Palestinian Christian leaders, such as Latin Patriarch Michel Sabbah, have come out forcefully in support of the Palestinian cause.

“There is no freedom and no justice when it is on account of others,” said Sabbah, speaking on October 31 at the Vatican. “In these difficult days, in the midst of the actual conflict, we say that the Palestinian people should regain their freedom and justice, which are part of their legitimate rights.”

For most Palestinian Christians like Duaybis, who have always lived alongside Muslim neighbors in mixed communities like Ramallah, the feelings of allegiance to the Palestinian cause, and even Islamic symbols, are integral to their own self-identity.

“Al-Aqsa, that’s me, my identity card,” said Duaybis, referring to the Muslim holy site. “If you take away my purse, and then offer to return it without my id, I won’t feel complete. Israel has already taken 78 percent of what was once Palestine. I don’t want to only get pieces of Jerusalem.”

Duaybis is a member of a Christian prayer group that meets every week at an east Jerusalem Christian institution known as Sabeel. Sabeel promotes a Palestinian form of liberation theology developed by the center’s founder, Dr. Naim Ateek, a former Anglican canon in Jerusalem. Meeting in a small stone room off a back street in east Jerusalem, these middle-class Palestinians, attired in conservative suits and pantsuits, share the Eucharist, sing hymns, and talk about the ongoing conflict.

For these Christians, today’s Palestinian struggle against Israel is the struggle of Jesus against an unjust Rome, or of the Old Testament prophets who proclaimed freedom and justice against the wishes of temporal rulers. Seen from this perspective, the Israeli retaliatory strikes using tanks and missiles are an extreme reaction to Palestinian demonstrators using stones and Molotov cocktails, and even to Palestinian sniper gunfire.

Israel considers its recent peace offers as magnanimous gestures to Palestinians, but Nora Carmi, another member of the prayer group, believes the negotiating process is one-sided. Years of Israeli land confiscation, settlement-building, road blockades, and Arab home demolitions have left the people’s frustrations to simmer as negotiations dragged on, she said.

Last summer’s peace offer to Arafat by Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Barak was seen as a humiliation. Barak offered to divide Jerusalem’s Old City and the mosque site into separate zones, each zone controlled either by Israel or by Palestinians.

“These seven years of peace negotiations have been very unbalanced for Palestinians, who wanted to see the fulfillment of their dreams and didn’t see it happen,” said Carmi, who is also a program administrator at Sabeel. “It drove us to the edge. In Camp David, people felt that the peace that they were offered was merely a surrender.

“It was very clear people would react. We didn’t know how. But thanks to Ariel Sharon, a direction was found,” she said, referring to the Israeli opposition leader’s Sept. 28 visit to al-Aqsa, which touched off the first round of riots.

Torn between tolerance and justice

Carmi’s personal story is typical of many Christians in this region who are forced to navigate the tumultuous currents of Middle East history. A tall, gentle-faced redhead, she was born in Jerusalem to an Armenian family, which fled to Palestine in 1917 from Turkey, escaping the Turkish genocide of the Armenian community.

Her family was forced to flee again from a west Jerusalem neighborhood to the city’s eastern Arab sector when the city was divided between Israel and Jordan in 1948. Carmi thus became a refugee in the city of her birth. Like many local Christians, Carmi has tried to maintain a balance between her commitment to tolerance and reconciliation and her quest for justice for Palestinians.

Both, she says, are rooted in her Christian faith and experience.

“I grew up among the historic sites and the monuments. I studied in the school Ecce Homo, located in the place where Jesus was put on trial,” she says. “For me, these are not just tourist sites but living, breathing places.”

“Yet sometimes, I feel that this fight over Jerusalem is not a fight over people loving Jerusalem,” she said.

“It reminds me of the Bible story of the two women who came before King Solomon, each claiming the same newborn baby, and how the real mother protested when Solomon said that the baby should be divided into two. I don’t want this baby, called Jerusalem, to be killed.

“I remember standing at the Mount of Olives overlooking Jerusalem’s Old City with a group of Presbyterian tourists at 8:45 Thursday morning, Sept. 28, when Sharon first entered the al-Aqsa Mosque compound. We could see the soldiers around the mosque, and the helicopters flying around, and my silent prayer was, Oh God, not another massacre.”

Elaine Ruth Fletcher is a reporter for Religion News Service. ©2000 RNS.

Related Elsewhere

See today’s sidebar, “Ariel Sharon: Mideast Peace Process is Dead.”

This story originally appeared as a Religion News Service feature.

See the latest on the Mideast Peace Process from various news sources at Yahoo’s full coverage.

Earlier Christianity Today articles on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict include:

How Evangelicals Became Israel’s Best Friend (Oct. 5, 1998)

Jerusalem as Jesus Views It (Oct. 5, 1998)

Christmas Plans for Bethlehem Scrapped | Escalating violence cancels millennial celebration in town of Christ’s birth. (Dec. 1, 2000)

Lutheran Bishop’s Appeal from Jerusalem | Religious leader’s letter requests prayer for Christians, Jews, and Palestinians in troubled region. (Nov. 10, 2000)

Latin Patriarch tells Israel to Surrender Lands to Palestinians | Catholic leader says Israel will never have peace unless it “converts all of its neighbors to friends.” (Nov. 1, 2000)

Fighting Engulfs a Christian Hospital in Jerusalem | Lutherans call conflict on their hospital grounds “an affront” to humanitarian purposes. (Oct. 16, 2000)

More coverage of the religious angle of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is available from Beliefnet.

Copyright © 2000 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.