Martin and Gracia Burnham were running again. For the fourth time in two weeks, the Armed Forces of the Philippines had found the American missionaries and their kidnappers, the Muslim terrorist group known as the Abu Sayyaf. Each of the last three times, the military had come in with guns blazing and reckless disregard for the hostages. And each time, the Abu Sayyaf had slipped away with its captives—the result of incompetence and corruption in the military’s ranks.

The Burnhams were not yet used to the sound of M16 fire and bullets whizzing by their heads. But this time, there was a sound wholly unfamiliar to them: a thump, followed by a shwoo woo woo, then another thump, and an explosion.

The Burnhams ducked, then stared at each other, eyes wide with shock, disbelief, and anger. “They’re shooting artillery at us!” Martin shouted, incredulous. “They have to know the hostages are here—what’s this heavy firepower about? These must be the most accurate artillerymen in the world; they think they can fire from ten miles away and kill the Abu Sayyaf but avoid us?”

The Burnhams did not imagine then that they would endure 362 more nights in the jungle and 13 more firefights between their captors and the Philippine military. But they already knew their situation was desperate.

“The Abu Sayyaf didn’t want to be recognized by the Armed Forces, of course, and neither did we,” Gracia Burnham writes in her new book, In the Presence of My Enemies (Tyndale). “We knew. … that a frontal attack to rescue us would probably turn out badly.”

Speaking to Christianity Today, the former New Tribes missionary is more specific. “We knew there would be a rescue attempt, and we figured both of us would die in it,” she says. Abu Sayyaf leaders had arranged for the Burnhams to appear on a Southern Philippines radio station, but Martin’s pleas to stop the shooting were truly heartfelt, Gracia says. “The Abu Sayyaf is going to survive this operation,” he told the military. “But the hostages will not.”

He was mostly right. On June 7, 2002, when the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP) came with guns blazing for the last time, the Abu Sayyaf shot all three remaining hostages. Almost all of the captors escaped, and Gracia Burnham was the only hostage who survived.

Burnham says she puts the blame for her husband’s death on the Abu Sayyaf, not on the AFP, but it’s clear that her anger doesn’t stop with the rebels. When she talks about the operation that freed her and killed her husband, she refers to it as her rescue, but makes big quotation marks with her fingers. “What would I call that day?” she says. “I don’t know. Sometimes I call it the day Martin died.”

“The AFP wanted to help us hostages, but pulling off an operation that sensitive was simply beyond their training,” she writes in her book. “At this point, we knew that our only real hope of getting out alive lay instead in negotiation. And for the Abu Sayyaf, negotiation meant only one thing: ransom money.”

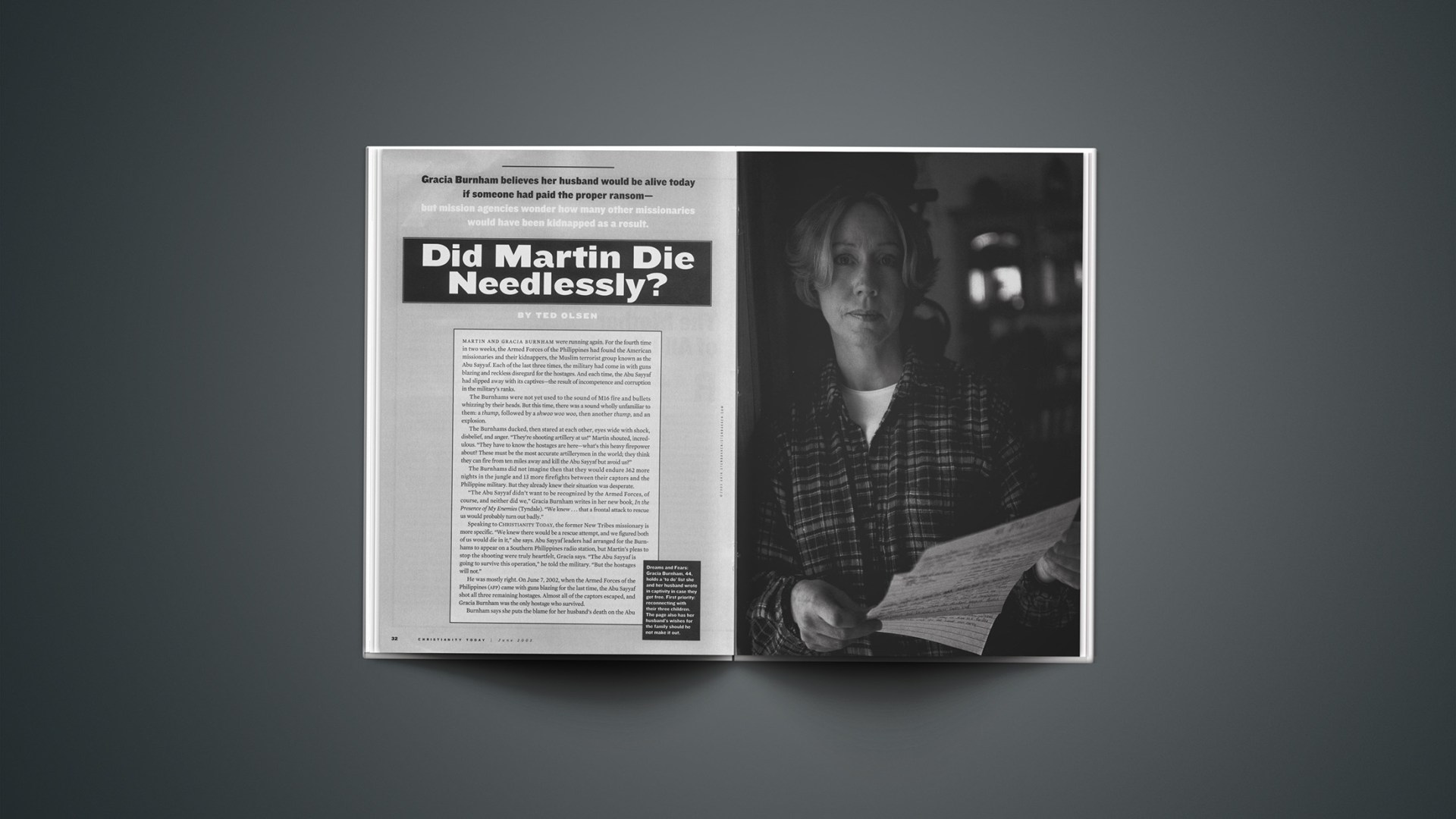

In her book, and in the few speaking engagements and interview requests she has accepted since her return to Rose Hill, Kansas, several miles outside Wichita, Gracia Burnham is unapologetic in her support of ransom payments to free hostages. She listens politely when people tell her that it would have been “immoral” to try to ransom them, or that doing so would put other missionaries in danger of future kidnappings. But it’s not easy to hold her tongue, and she says she wants to tell them, “You go stand in that corner over there, and you don’t leave until someone pays a ransom for you. You see how long that ransom policy holds up in your mind.”

It didn’t take long in captivity before the Burnhams changed their minds. “If we can trust the Lord for a million dollar [ransom], which is something totally beyond our reach, we can trust the Lord that the million dollars never buys a weapon or blows anybody up,” Martin told his wife.

Ransoms may be scandalous and costly, she says, but they’re hardly immoral. “Ransoms: that’s what Jesus did, right?” she asked CT. “Jesus paid a ransom for us, and it cost him everything.”

Officially, the government and missions community strongly disagree with Burnham on the usefulness and effect of ransom payments. But in boardrooms and government offices both during and since her captivity, there have been quiet debates—and subtle policy shifts—on the issue. After all, the world is a very different place from what it was on May 27, 2001, when three gunmen disrupted the Burnhams’ anniversary getaway by bursting into their room at the Dos Palmas Resort.

Dropping the blanket policy

In February 2002, after a long battle between the Pentagon and the State Department, the U.S. government quietly changed its policy on overseas kidnappings. Under a new National Security Council-led committee called the Hostage Subgroup, the federal government will review each case in which an American is kidnapped overseas. “What the new policy ensures is that the government will no longer ignore cases simply because a private citizen is involved, or because the kidnapping seems to be motivated primarily by money rather than political goals,” an unnamed official told The New York Times.

In what an official called a “subtle but very important” shift, the government also changed its policy on ransom payments. It still promises “no deals, no concessions,” but it dropped a blanket policy barring private companies and individuals from paying ransom. American companies and families have paid numerous ransoms over the years, but now the government will merely discourage such actions rather than censure them. Now the government will continue to cooperate with families and companies, even if they choose to meet kidnappers’ demands.

As University of Missouri historian Russell D. Buhite recorded in Lives at Risk (Scholarly Resources, 1995), it’s not as if American foreign policy has always been guided by a rigid “no ransom/no negotiation” policy. In 1901, 11 days before Theodore Roosevelt became President, American missionary Ellen Stone was taken hostage in Turkey. Her kidnappers, Macedonians who sought an independent state, demanded 25,000 Turkish pounds (about $1 million today). Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Teresa Carpenter calls it “America’s first modern hostage crisis” in her book The Miss Stone Affair, published this month by Simon & Schuster.

Rather unlike the Burnhams’ situation, however, Stone had a mission board that was amenable to paying the ransom and a President who was willing to help with it. In fact, Roosevelt told the agency that Congress would reimburse any privately raised funds. Such eagerness was largely based on Stone’s sex. “If a man goes out as a missionary he has no business to venture to wild lands with the expectation that somehow the government will protect him as well as if he had stayed at home,” Roosevelt wrote. “If he is fit for his work, he has no more right to complain of what may befall him than a soldier has in getting shot. But it is impossible to adopt this standard for women.”

It was the U.S. consul in Constantinople who argued that such an action would only encourage more kidnappings. He did not invent the idea, of course. Nineteenth-century missionaries to Africa debated whether ransoming slaves would only encourage more slavery. Protestants generally believed that it would, and were forbidden by their agencies from such actions, while Roman Catholics bought the freedom of several slaves. Despite the consul’s efforts to circumvent a payment, one was made—albeit smaller than the demand—and Stone was freed. But the press argued that Roosevelt had been too soft, and the President wrote to Secretary of State John Hay that “never again will we sanction the payment of a ransom.”

Nevertheless, later presidents would similarly negotiate, bargain, and ransom their way out of hostage crises, and it wasn’t until the last quarter-century that a hard line was more consistently articulated—though still forsaken, as in the Iran-Contra affair.

These days, however, as Gracia Burnham found out, public opinion and the government agree with Ronald Reagan’s assertion that “once we head down that path [of negotiation], there will be no end to it—no end to the suffering of innocent people, no end to the ransom all civilized nations must pay.”

Even after the U.S. government adopted its new policy, it was not easy for Gracia Burnham’s family to put a ransom payment together. Her uncle managed to convince an American philanthropist to offer 15 million Philippine pesos (about $330,000) for the couple, but it was far less than the $1 million demand. Burnham says that none of the money came from the government, as some had speculated.

As the U.S. government was officially cracking open the door to ransom payments, so was U.S. Representative Todd Tiahrt (R-Kan.), who represents the Burnhams’ district. He was strongly against paying ransom early in the Burnhams’ captivity, but near the end he talked about ransom’s benefit.

“If we were just to outright pay for the release of hostages, that would only reinforce that type of blackmail, and we would end up caught in the same trap over and over. So, I don’t think outright payment is necessary,” he says. “However, it should be a tool that’s available if [the government] thinks it could be used to draw these people out, especially when they’re in hiding.” He compares ransoms to money police spend on securing a drug bust.

But the money paid for the Burnhams neither drew out the Abu Sayyaf nor ransomed the hostages. In late March, two Abu Sayyaf leaders, Abu Sabaya and Abu Musab, sat the Burnhams down.

“Someone has paid a ransom for you: 15 million pesos. So this is really, really great,” they said. “But we are going to ask for 30 million pesos more.”

Burnham says that just a day or two earlier, she had heard Sabaya tell someone on the phone, “Take anything they offer, because we are ready to get this over with.” She pleaded with him to take the initial offer.

“No, no—the person who paid this ransom said that if we require more, they’ll come up with it. This won’t be a problem.”

The mood was celebratory. Members of the Muslim group shouted, “The money’s been paid! You’re going to get out of here! Allahu akbar [God is great]!” But more money never came.

Burnham doesn’t know who said there was more money to be had, but she says it was a “stupid thing to tell them. When I was being debriefed, I asked someone at the embassy, ‘Where was the rest of the money?’ and they told me there never was any more. So I think what happened with our ransom was that it wasn’t enough. It wasn’t enough.”

“It’s a good example of if you had all the resources in the world, would it really achieve what you want?” says Dan Germann, vice chairman of New Tribes Mission. “They have an insatiable appetite.”

Germann says there is a continuing discussion about New Tribes policies and procedures on kidnappings, but that the mission agency still believes the no-ransom policy “really does serve well those communities that need to be out there in some of the more vulnerable places of the world.” He says that in Colombia, which has the world’s most kidnappings, instances of American hostages are down, while other groups remain up. “That has come at a high cost,” he says, referring to three New Tribes missionaries kidnapped there in 1993.

“There’s something about trying to read what happens in the hearts and minds of hostages that is just heart-rending,” says Germann, who was on the crisis management team for both the Burnhams’ captivity and that of the three missionaries kidnapped by Colombian rebels (they have since been declared dead). “But it probably isn’t the thing that actually creates the kind of policy and the kind of response that’s most appropriate for seeking the release of these people.”

Crisis moment

Those directly affected by the Burnham crisis are not the only ones rethinking their policies on kidnapping and ransom. “Although there’s a general discussion at the level of mission administration in this country, it really to a large extent depends on whether the mission agency in question has missionaries in trouble spots,” says Jonathan Bonk, executive director of the Overseas Ministries Study Center. “The discussion kind of goes away when there’s no longer kidnapping taking place.”

In fact, several organizations contacted by Christianity Today said that there are instances, albeit few, in which ransom is morally acceptable. Bob Klamser, executive director of Crisis Consulting International, which advises many mission organizations, gives a hypothetical example of a kidnapped missionary couple with a $1 million ransom demand. After 18 months in captivity, they have been treated well, a doctor has been admitted to treat their injuries, and the kidnappers lower their demand to $10,000 for each hostage.

“That $20,000 is not going to encourage that group to do future kidnappings. They lost money on the deal. Now back up. We have the same kidnapping, the same kidnappers, the same victims, and somebody wants to pay the $20,000 a week into the kidnapping. … $20,000 for a week’s work is not bad wages, and probably would encourage future kidnappings. You have to evaluate them case by case.”

Bonk believes ransom would be okay if there are no other missionaries in the area where the kidnapping occurred, or “if you’ve got the means to make sure that your missionaries are very, very secure after you’ve paid that ransom. But if by paying that ransom you’re putting other missionaries in danger, then of course you just can’t pay.”

He generally agrees with the premise that ransoms paid for a missionary put others at risk, but says there’s a problem with the argument: kidnappers don’t distinguish between American missionaries and other Americans. “I don’t think outsiders necessarily make a distinction between Americans who earn their living selling oil and Americans who earn their living selling religion, as they would see it,” he says. “The big thing is that they’re American; they’re potentially a source of funding.”

American wealth puts missionaries at risk in another way, Bonk adds: “As the West becomes more and more of a pariah, as the perception grows that the West is to blame for everything, to that extent anyone associated with the West, including religious people, are vulnerable.”

Burnham says in her book that an Abu Sayyaf leader was disappointed to find out, a few hours into the abduction, that she and Martin were missionaries. “He had hoped that we might have been European—or at least American—business types, whose company would readily pay to get us back,” she writes. “Mission groups, on the other hand, were poor and on record with standing policies against ever paying ransom. … Then he returned with this ominous announcement: ‘Yours will be a political ransom. We will make demands, and we will deal with you last.’ “

Burnham now feels like she made a mistake. “We were clueless,” she told CT. “We should have said, ‘Okay, we’ll call so and so,’ even if we just made up somebody’s name. But we sat back because we don’t know to do that. Because of our Western mindset [that ransoms were wrong], we didn’t do what everybody else did, and we missed an opportunity.”

Her fellow hostages knew what to do, Burnham says, because Philippine society is accustomed to ransom as a way of life. “Our culture says it’s wrong to pay a ransom,” she says. “In their culture, they grow up paying bribes and ransom and paying off someone.”

Burnham tells the story of how her son’s bicycle was stolen on the mission field, and it was obvious who had taken it. “Martin proceeded to do the logical thing—at least so far as we understood Philippine ways,” she writes. “He sent a go-between to talk with the parents, politely asking for our bike back. They immediately got very upset and embarrassed. Our go-between returned to explain that a person doesn’t accuse the other person of wrongdoing. Instead, the person offers a ransom for the property, and then everyone can be happy again.”

The Burnhams, feeling uncomfortable about paying cash, ransomed the bike for some cake and cookies. But as with bribes, the Burnhams maintained a consistent ethic. “We had more than one ethical debate with ourselves about whether this was wrong for us to do,” she writes. “As the years went on, we decided the wrong was on their part, in stooping to extortion, rather than our part for doing the necessary thing in response.”

In fact, Burnham told CT, addressing such matters in Philippine culture is one reason she wrote her book. “It may embarrass them that I put it in my book, or it may make them think. When I was writing this, part of my goal was to get them to think through their culture,” she says. “In their culture, you can explain anything away and it’s not wrong anymore.”

Not everyone shares her perspective. Anthropologist Miriam Adeney, who spent four years working in the Philippines with InterVarsity and other organizations, says she never noticed a ransom-friendly culture there.

Regardless of what Filipinos think about ransom, one culture that was intimately familiar with the concept was ancient Israel. And this goes to the heart of Burnham’s question: “Ransoms: that’s what Jesus did, right?”

It’s not a new thought to her. Once in captivity, she told her fellow hostages, “I’m so glad that when Jesus paid a ransom for us, we didn’t have to wait for it to arrive, and we didn’t have to wait for him to decide if he was going to do it or not. Before the foundation of the world, he knew he was going to have to ransom us. And he did it, and it cost him everything.”

If Burnham wants to make Filipinos rethink their attitudes, here is where she wants American Christians to rethink theirs: “Maybe our thinking about ransom is wrong. Go ahead and pay the ransom and get your loved person, your loved one, back, even if it takes everything you’ve got.”

The argument resonates with Bonk. “Our whole evangelical theology is based on ransom,” he says. “That’s the core of our theology, that Jesus was a ransom for us. And that’s exactly what the evangelical missionaries are there to proclaim.”

But Hans Boersma, assistant professor of religious and worldview studies at Trinity Western University, says equating a kidnapper’s ransom demand with the Atonement—Christ’s saving death on the cross—is theologically problematic.

“She’s taking the word redemption or ransom and she’s running away with it,” says Boersma, whose book Violence, Hospitality, and The Cross: Understanding the Atonement will be published by Baker Academic next year. “She’s applying all of her understandings of what ransom is onto the biblical picture. There is no party that’s being paid biblically, and to think that there is a party [like Satan] that receives the ransom money would be to overextend the metaphor. There is someone who cares, to be sure. And there is someone who sets free, someone who liberates, in the biblical understanding of redemption. But the way in which ransom is paid is not by means of a monetary sum, nor is anybody being paid.

“Whenever we talk about what the death of Christ means, we’re using certain metaphors,” Boersma says. “One metaphor among many is the idea of a price being paid, of a ransom, and it’s not a very worked-out metaphor. The idea that somebody is being paid is not part of the metaphor. That a payment is made is part of the metaphor.”

That’s not to say that the doctrine of the Atonement does not have specific applications. Boersma agrees with Burnham at least on that point. “It costs a great deal to set people free,” he says.

And today, it often costs a great deal to tell people about freedom. In the last few months, American missionaries have suffered fatal attacks in Guatemala, Yemen, Jordan, and elsewhere. In March, one of the Burnhams’ missionary friends in the Philippines, Southern Baptist Bill Hyde, was killed in an airport bombing.

Missions continue to face the tricky task of mixing compassion for workers and faithfulness to evangelism. Missionaries must be increasingly willing to die—and to be taken hostage—and policymakers must ensure that, within that acknowledgement of possible sacrifice, the missionaries are not being placed at additional or unnecessary risk.

Ted Olsen is Christianity Today‘s online managing editor. Assistant online editor Todd Hertz contributed to this report. For a full interview with Gracia Burnham, as well as our full coverage of the Burnhams’ captivity, visit christianitytoday.com/go/burnhams.

Copyright © 2003 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.

Related Elsewhere

Also appearing on our site today:

Gracia Burnham: ‘I Speak My Mind’ | The former hostage talks openly about what she learned about God, her Muslim captors, and herself during her captivity.

Christian History Corner: The Day the Ransoming Began | A gripping new book details the first American missionary hostage crisis, over 100 years ago.

Dogging the Story | Christian media can play a special role in cases like the kidnapping of the Burnhams.

In the Presence of My Enemies is available at Christianbook.com.

Previous articles on the Burnhams’ captivity are available at our Martin and Gracia Burnham: CT’s Full Coverage page.

Last year, Todd Hertz reported on U.S. and missions approaches to ransom payments as the government introduced its new kidnapping policy.

New Tribes Missions has a section of its website dedicated to the Burnhams.