Ayat Al-Akhras was an 18-year-old living in a Palestinian refugee camp. She was beautiful, an A student, and already engaged to be married.

Rachel Levy was a 17-year-old Israeli living in Jerusalem. She was striking, free spirited, and a loving daughter and sister.

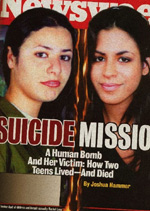

On March 29, 2002, Rachel’s mother asked her to go to a local supermarket to pick up ingredients for Sabbath dinner. While Rachel was in the store, Ayat entered the building and detonated a purse full of explosives, killing herself, a security guard and Rachel. The two girls looked so remarkably alike that pathologists had difficulty correctly reassembling their remains. When Newsweek magazine placed their pictures side by side on its cover, many readers suddenly perceived the conflict in the Middle East less as an abstract issue of politics and more as a human tragedy of needlessly wasted lives.

|

Hilla Medalia is a talented young Israeli filmmaker who was completing her master’s degree in the United States at the time of the bombing. Almost immediately after the incident, she began work on a documentary about Rachel and Ayat and their families. A short student film (Daughters of Abraham) eventually blossomed into To Die in Jerusalem, a heart-rending and thought-provoking feature currently airing on HBO, screening at film festivals, and available for purchase online. The film focuses on the mothers of the two girls and climaxes with an emotionally charged meeting between them—via satellite, even though they only live a few miles apart.

To Die in Jerusalem is a film about an ancient and enduring conflict embodied by two heart-broken mothers and two lives cut tragically short. It leaves viewers moved and frustrated and anxious for change. CT Movies had an opportunity to speak with Medalia about her five-year quest to tell a devastating and important story.

How did you become aware of the tragic events of March 29, 2002?

Hilla Medalia: At the time of the bombing I was a student at Southern Illinois University. I wanted to do a documentary about the Middle East for my thesis film, and I was basically looking for stories. Then this bombing happened, and I saw the picture of the two girls in the newspaper, and I was really stunned and touched and moved. And I thought that it could be a good story.

At the time I never thought about the meeting between the mothers. I just wanted to talk to the mothers [separately] and tell the story of the two girls. Actually, the first time that I met Avigail, the Israeli girl’s mother, she told me that she wanted to meet the parents of the Palestinian girl. But at the time I wanted to graduate, and also I felt it was a bigger journey than I could document then. In essence I needed to prepare myself and also the characters and everyone else involved. I wasn’t ready [for the mothers to meet].

So I created the short Daughters of Abraham. And then it won the Angelus Award [for student filmmakers], and through that I met John and Ed Priddy from Boise, Idaho. They wanted to help me make a feature-length film, so they gave me the initial money to do To Die in Jerusalem. And then at a later time HBO got in the picture, and I got a grant.

How is To Die in Jerusalem different from Daughters of Abraham?

Daughters of Abraham is a very naïve look, and it’s basically just interviewing the two mothers and some other footage. There is no meeting. The story is told with a very optimistic voice.

I matured through this film. To me, To Die in Jerusalem is a real depiction of the current situation, and it’s a microcosm for the whole conflict.

Does it feel like this story has dominated your life for the last six years?

On and off, yeah. When I started, I really just wanted to make a film for school, and I was hoping to graduate in May and maybe get it aired on the local affiliate. I never thought it would have such a wide reach. The first night on HBO, maybe half a million people watched it. And now it’s being screened all over the world and there are millions of people watching the film. It’s pretty amazing.

No kidding. HBO originally tried to send a couple of known American producers to get the story and they couldn’t get anywhere with Ayat’s family. How were you able to gain the Palestinian family’s confidence and get access to them?

Don’t forget I’m Israeli. That’s actually supposedly harder. It took time. Perseverance. I was slowly working it out and developing my relationship with them, and the keys were to understand the culture and be sensitive to them. I don’t know the filmmakers that tried and why they weren’t able to, I can only tell you how I kept coming and coming and coming and developing a relationship until we got close enough.

At the beginning, actually, I was too scared to go in. So I used to meet my crew at the [refugee camp] checkpoint and send them in. For the longest time I would tell them “You know, today I’m too busy. I’ll see you after.” I grew up near Tel Aviv, and the closest camp to my house is maybe fifty miles away. I’d never seen a refugee camp in my life.

Really?

You don’t just go to a Palestinian refugee camp if you’re Israeli. Before the film, I probably thought about the refugee camp the same way you do. I had no idea really. And I was scared of the unknown. So [finally my crew] literally put me in a car and took me over there. It took a few times before I felt comfortable, and then it was great. And I was okay even to walk by myself in the camp.

But then the time where I was stopped [and taken to the police station for four hours] was really a tough time for me.

How were you treated?

They treated me fine. But it was just the hard realization of what it meant. We were near the market and all the people were saying “There is a Jew in the car.” What I realized is that I’m in the midst of a conflict and I represent one side of it, so it doesn’t matter how many Palestinian friends I have and what kind of work I’m doing, I’m still Israeli. And you know it only takes one extremist … so it was really scary and disappointing.

For every Israeli, the police headquarters are very symbolic because there was a famous incident when two Israelis got lost and somehow got into [a Palestinian refugee camp] and were taken to the police headquarters and lynched. But of course like everybody else in the region we have a really short memory. So actually during the [eventual] satellite meeting between the mothers, I was with the Palestinian family.

The film seems very intentionally balanced between the points of view of the Israeli and Palestinian families. Was it important to you to try to be impartial in how you showed both sides?

I always try to be careful with the word balance, because I don’t know if there is balance. What is balance? And I would also say that I’m Israeli, so I have a natural bias. But I think that what I was trying to do was to really stay true to the mothers in presenting their truth. And I think to me also it shows how complex the conflict is because nobody’s right and nobody’s wrong. Or in other words, everybody’s right and everybody’s wrong.

Did you find that your own views changed at all through the making of the film?

I think that spending so much time with Avigail, and spending time at the camp, were great and deep learning experiences. It really created deeper understanding. But I don’t think I changed my views.

How are the conditions in the camp?

Bad. There are no roads, everything looks unfinished. Everything is like bare minimum. But I think more than anything is the notion: “We are not free.” The notion you don’t have a country is harder than the actual physical conditions.

That certainly seems to come out in the film. In the end there were too many obstacles to having the mothers meet in person, so they met by satellite. How did the meeting compare with your hopes for it?

I was born hopeful and I always do hope to get to a reconciliation or understanding and peace. But that’s not realistic, because reality is different, and we are in a very tense time. The meeting is the microcosm for the conflict, unfortunately.

There were factors to consider. The meeting took place in 2006, right after the Lebanon War. A time of war, it’s always more tense there. If the meeting happened at a different time, I’m sure it would have been different.

Avigail was very brave to initiate the meeting, but I also think that Ayat’s mother Um Samir was brave to come, knowing that her daughter killed Avigail’s daughter. The meeting took four hours and none of them stood up and left. So to me that’s encouraging.

The meeting was so intense, but with all the intensity all of them stayed. Somewhere, somehow they were really hoping to get to an understanding. The problem is that each of them was trying to achieve something else from the meeting.

What do you most hope viewers take away from watching the film?

The important thing is that after every screening there is a very interesting, moving, emotional discussion. That’s the big picture. It makes people talk and discuss and hopefully understand each other. It makes people see the other side.

How does the situation in the Middle East now compare to 2002?

It’s terrible. Now there are missiles in Israel and there are problems in Gaza. There are all these different things happening. We have weak leaders on both sides. When you take the majority of Israelis and majority of Palestinians, we agree on most things. But the problem is that the voice you hear is the voice of the extreme.

When we see the film, and we’re moved, how do we respond? How can we make a difference?

There are many organizations that are helping. There are many apolitical movements, not just presenting a party. They are trying to create dialogue and move politicians and leaders to actually take action. I put some of them on my website. There are organizations that create meetings between parents. There are organizations that educate.

Even if you do a little, it’s a lot. I mean, I just made a film … but we must think that it makes a difference.

Copyright © 2008 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.