It’s common to hear conservative Christians, perhaps especially those in Washington, D.C., explain that politics is downstream from culture. But Mark Rodgers is one of the rare few who decided to move upstream.

Even when he was staff director of the Senate Republican Conference, a position he held after serving as chief of staff to Sen. Rick Santorum, Rodgers was fond of quoting Damon of Athens: “Give me the songs of a nation, and it does not matter who writes its laws.” While it may seem an odd sentiment from one of Capitol Hill’s top staffers, it didn’t mean that Rodgers didn’t see meaning in his work. But reading books by the likes of sociologist James Davison Hunter, John Stott, and Francis Schaeffer made him and others in the group eager to “make a difference”—which meant developing better ties with the entertainment industry.

“As we expanded our outreach to artists, we kept hearing, ‘I have a great idea for a project, but I need capital,’ ” Rodgers said.

When the Democrats won control of Congress in 2006 and his boss lost his reelection bid, Rodgers found his boat upstream. He’s still in the Washington area, but now he’s director of the Wedgwood Circle, an angel investment network.

“Angel investing” was originally an entertainment term used to describe the investors in Broadway’s unpredictable shows. Today, nearly all of the 300 or so angel investing groups focus on new technologies like software and biotech. They occupy the spaces between creators’ seed funds from friends and family and venture capital firms, facilitating deals between entrepreneurial investors and investment opportunities. In the case of Wedgwood Circle, potential members must have a net worth of $1 million and pay an annual fee of $6,500. Since Wedgwood’s launch a year ago, 26 investors have already signed on.

Wedgwood’s mission is broad: promoting redemptive work in all sectors of the entertainment industry. Some assume the group is out to promote Christian products. But Rodgers says the people who want to make those products and the people who want to invest in them are already connected.

“We want to invest in Juno, not the Jesus film,” he says. That’s the sensitive part. He likes the Jesus film. He was enthusiastic about The Passion. He listens to CCM. But Wedgwood isn’t about creating Christian-culture artifacts. He’s about creating artifacts that are “true, good, and beautiful for the common good.”

Others have seen the group as a stealth culture-war vehicle. But Rodgers emphatically denies it, noting that the network consciously rejected the idea of having a list of “issues” to address.

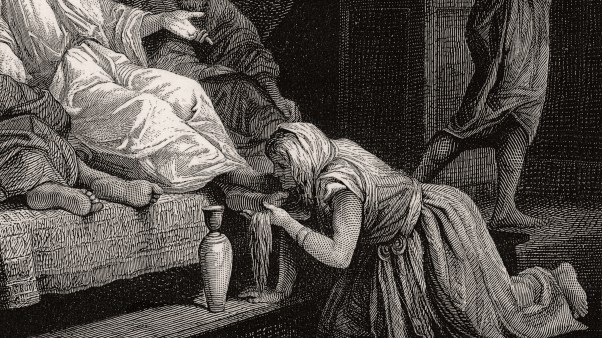

Still, an early Wedgwood deal focused on a documentary film and album on the modern slave trade, echoing the group’s abolitionist namesake, Josiah Wedgwood. The ceramics businessman, a peer of William Wilberforce, produced a cameo that became an icon of the anti-slavery movement: a naked slave kneeling in chains below the inscription, “Am I not a man and a brother?”

Rodgers likes the ambiguity: maybe the kneeling slave is praying, or maybe he’s pleading. The inscription, too, is provocative. “It raises a question: Where in our culture [do] we need to be? Art is better when it does that. It’s propaganda when it answers it.”

Rodgers also likes the cameo because it was well crafted and made Wedgwood a lot of money. The trick for Rodgers’s group, he says, is “to work out the tension between patronage and profit.”

Ted Olsen is CT managing editor of news and online journalism.

Copyright © 2008 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.

Related Elsewhere:

Wedgwood’s website has more information.

This article is the third of five profiles in Christianity Today‘s cover package on “The New Culture Makers.”

Christianity Today also wrote about artist Makoto Fujimura and the Prison Entrepreneurship Program.

Crouch spoke with CT about culture making on a local scale.