Back in the day, the evangelical fantasy went something like this: As you get settled into your airplane seat, you casually remove your Bible from your carry-on. A few moments of solemn reading later, your neighbor taps you on your shoulder. “Pardon me,” he says. “But I couldn’t help but notice a certain … peace about you. Where might I find that peace?”

In mid-2018, the fantasy has been flipped on its head. The pagan neighbor is now reading your tweets. “You’re so angry at Trump!” she gasps. “What can be driving such passion for justice and mercy? … An evangelical who opposes Trump’s policies? How can this be?” (There’s another version of the story where the neighbor earnestly wants to know about “these Christian values you keep talking about.”)

Those stories might even happen once in a while. The Spirit works in strange ways. Still, the apologetics potential in opposing Trump (or supporting him) is too easily exaggerated in our minds. Scripture promises that Christian unity will point the world to Jesus (John 17:21) and that good works will prompt non-Christians to glorify God (Matt. 5:16, 1 Pet. 2:12). It doesn’t indicate that our voting record can be the 21st-century equivalent of the Four Spiritual Laws.

With the US midterm elections a few months away, this is not a call to political silence, to a privatized, “spiritual” faith. Rather, this is a call to speak politically as the Bible does. We should be on guard against talking about Trump more than Paul talked about Nero—especially if we’re talking about Jesus less than Paul talked about Jesus.

Bible Subversion

It’s clear enough from a plain reading of Scripture that Caesars shaped the New Testament world. (That Roman cross is hard to miss.) But recent decades have provided a trove of scholarly and popular studies helping us to see the Roman background in words, phrases, and stories we’ve become too familiar with. Take Luke’s Nativity story: We might notice Augustus launching a tax census. But we may not know how much words like Savior, Lord, gospel, and peace were used in imperial propaganda to talk about Caesar.

A volume due out in September, Adam Winn’s Reading Mark’s Christology Under Caesar, is the latest helpful example. “Mark was written to address a crisis in his church that was created by Flavian propaganda,” Winn argues. “From the opening incipit Mark challenges the claims of Vespasian by boldly claiming that Jesus rather than Vespasian is the true Messiah and true Son of God.” Winn is swimming against the tide of most Mark scholars, but the historical context he illuminates is helpful. Yes, Roman Christians would have read Mark 10:42–45 as a critique of Caesar and his minions (“those who are regarded as rulers of the Gentiles lord it over them”). But Winn compellingly argues that the passage more importantly uses Roman political ideology to stress both Jesus’ power and his suffering, rather than (as many Mark scholars have argued) seeing Jesus’ suffering and death as a laying aside his power. In Winn’s words, Mark wants to show how Jesus “out-Caesars Caesar” as Messiah and Lord.

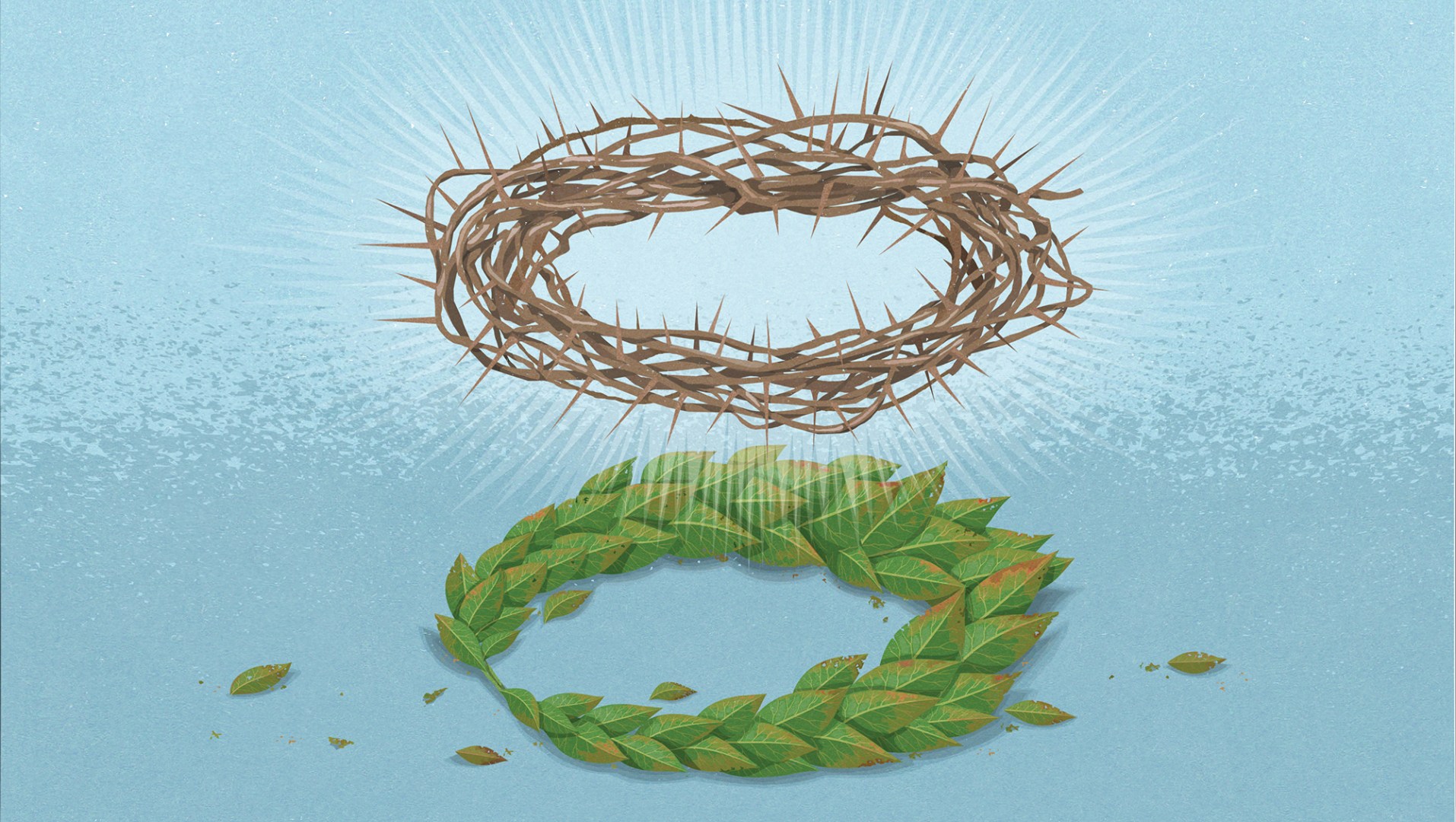

But here is a crucial point—Winn still thinks Mark was more interested in proclaiming Jesus as true Lord than in denouncing Caesar as a false one. And Mark never explicitly denounces Caesar. A growing chorus of evangelical scholars (popularized by N. T. Wright but not limited to him) have been saying, “If Jesus is Lord, Caesar is not.” Now evangelical scholars are uttering a word of caution: The Bible says “Jesus is Lord” a lot. It barely mentions Caesar and never explicitly says “Caesar is not.” As John Barclay notes, “Paul’s gospel is subversive of Roman imperial claims precisely by not opposing them within their own terms, but by reducing Rome’s agency and historical significance to just one more entity in a much greater drama. To oppose the Roman empire as such would be to take its claims all too seriously.”

Today’s Caesars and their enablers similarly want us to play by their own rules, with their own definitions. “Who will you vote for?” and “What’s your approval rating for Trump?” are not all that different from “Is it lawful to pay taxes to Caesar or not?”

In Ephesus, Paul “argu[ed] persuasively about the kingdom of God” (Acts 19). Idol craftsmen warning that his preaching “robbed [Artemis] of her divine majesty” incited a riot. The city clerk quieted the crowd, arguing that Paul “neither robbed temples nor blasphemed our goddess.” Paul seems not to have mentioned Artemis. He preached Jesus is Lord. The city raged anyway. Similarly, preaching “Jesus is Lord” and talking about his kingdom may be met with assumptions or misrepresentations about our political beliefs and attitudes. Don’t worry about it. As Paul said, “What we preach is not ourselves, but Jesus Christ as Lord.”

Ted Olsen is editorial director of Christianity Today.

Do you agree? Disagree? Let us know here.