When I was radioactive, I carried a card in my wallet to explain why I set off alarms at the airport with my body. The card read, “Rachel Jones has undergone nuclear medical treatment.”

I keep the card in my wallet, even though I no longer need to show it at airports. I love the card and I hate it. I love it because it says I had nuclear treatment, which simply sounds awesome. I hate it because that awesome-sounding treatment didn’t give me the ability to fly or glow in the dark. I love it because not everyone gets to step through an airport scanner and explain to the TSA staff why their body is lighting up the screen and that makes me feel special. But I hate it because it means I have cancer, which also makes me feel special, but not in a good way.

I have thyroid cancer. I had a total thyroidectomy followed by radioactive iodine treatment, which meant the pill a nurse delivered inside a lead container and only touched with gloved hands and a pair of tongs, I put into my bare palm and then into my mouth and swallowed. There was nothing epic or momentous about the moment of swallowing the little pill, other than the Imagine Dragons song Radioactive, which echoed on endless repeat in my mind.

I took the pill, walked out of the hospital, drove home, retreated to the basement, and isolated myself for three days from all humans and animals, hoping that the cancer would die.

I was now a danger to society. As my body leaked radioactivity, I could damage someone else’s body simply by proximity. No touch, no shared space, no common utensils or toilets. Everything I touched needed to be scrubbed down, the space in which I breathed needed to be ventilated. No one could come within eight feet of me.

The COVID-19 response has evolved from disrupting vacations and air travel to shutting down schools and prompting “shelter at home” decrees. People are isolating at home the way I self-isolated in my parents’ basement. Being radioactive didn’t give me a fever, and wearing a mask wouldn’t have made a difference for me, but I needed to avoid human contact. It was my body, not just my breath, that was dangerous.

The fact of my body as danger made me think not about the people wearing the masks but the people they are protecting themselves from. The sick. The contagious. Coronavirus. Radioactivity. Me.

In the New Testament, Jesus touched lepers (Matt. 8:1–4). He embodied culturally subversive compassion and fearlessness around contagious disease. People could judge and shun him for touching the untouchables. They might not want to share a communal plate at mealtime with him. They might decide he was foolish or reckless.

But Jesus didn’t care what others thought. He challenged them to choose to love, even at risk to themselves. I’m not saying we need to forget about social distancing. Jesus had miraculous powers both to heal and to protect himself from contagion that none of us have. Still, it is worth noting this counter-cultural behavior.

I used to think about the joy and awe the lepers must have felt as healing power swelled through them. But what I rarely thought about is what it must have felt like for the sick to know that their bodies, their own selves were dangerous. That the simple act of being in the presence of someone they loved put that person at risk.

My own sense of shame was real, though cancer and treatment were not my fault, just as contracting COVID-19 is not the patient’s fault —no matter their nationality or ethnicity, no matter what country they are in or came from or traveled through.

Fault or no, the fear that I would harm someone I loved was real. The waves of guilt pounded me: because of me, my family couldn’t do laundry in the basement, they needed to avoid part of the house, and the medical bills for this treatment piled up while I watched Netflix alone.

I can also imagine, on a small scale, what the lepers in the New Testament must have felt upon realizing they were healed. Not only stunned by the miracle, not only filled with worship for the God who brought it, but experiencing the reality of a joyful liberation. Now, they could hug their relatives without harming them. Now, they could share a meal without infecting anyone else. Now, they could worship in the temple alongside neighbors. They could live without fear of contaminating someone else’s healthy body.

As healed and whole humans, the lepers experienced newfound freedom to go anywhere and touch anything. A freedom to not be filled with concern if someone stepped too close, freedom to share a drink of water or a bed. Freedom to step inside the wedding dance circle and spin, no longer relegated to looking in from a distance. Freedom to participate and share, to join and belong. Freedom to never again socially distance themselves.

Love is reciprocal. When we love people, we want to be with them and touch them, express with our bodies what our hearts feel. Right now, we are choosing distance for love’s sake, but that is not our natural preference. When Jesus healed lepers, he enabled them to express love back.

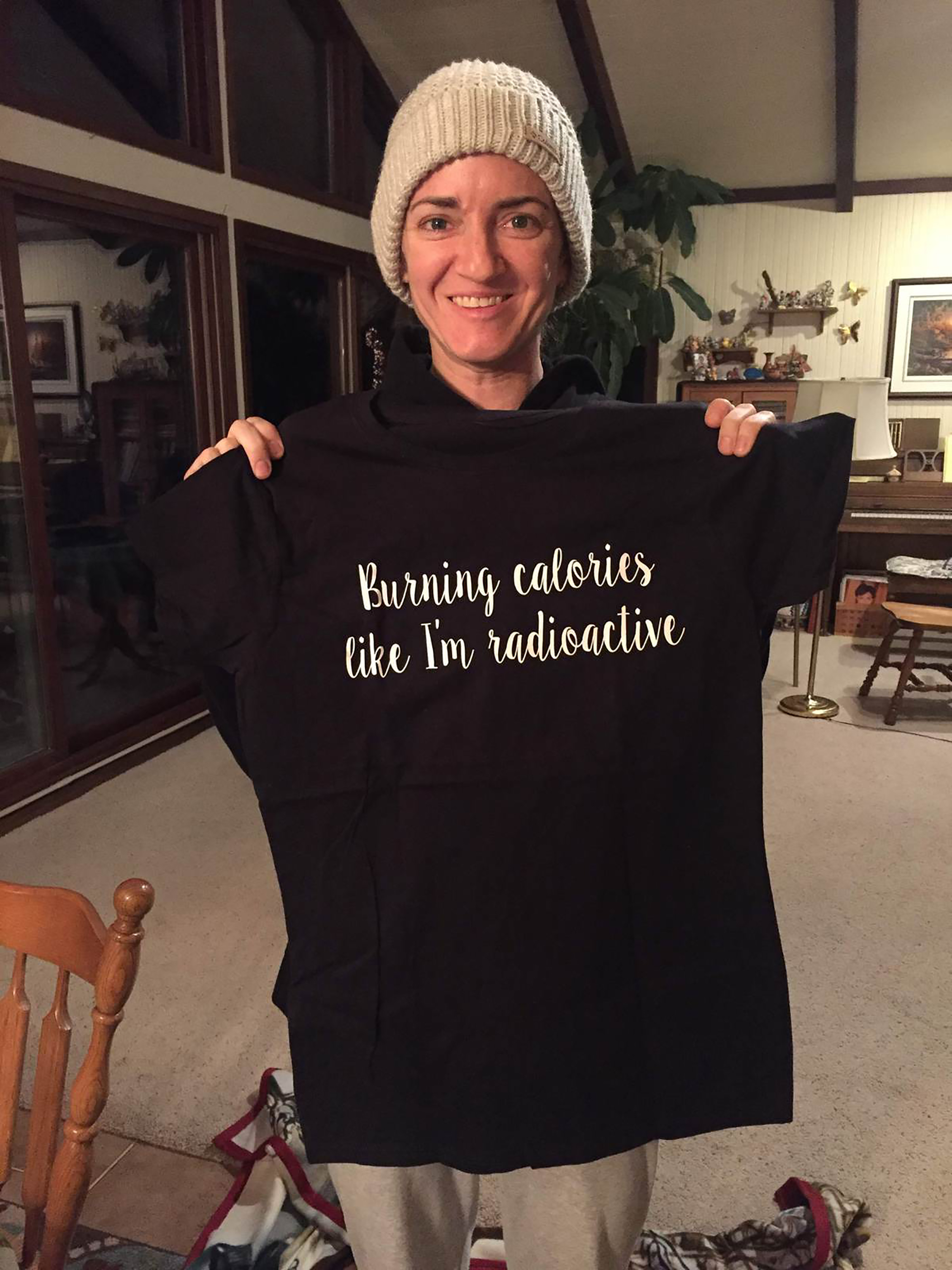

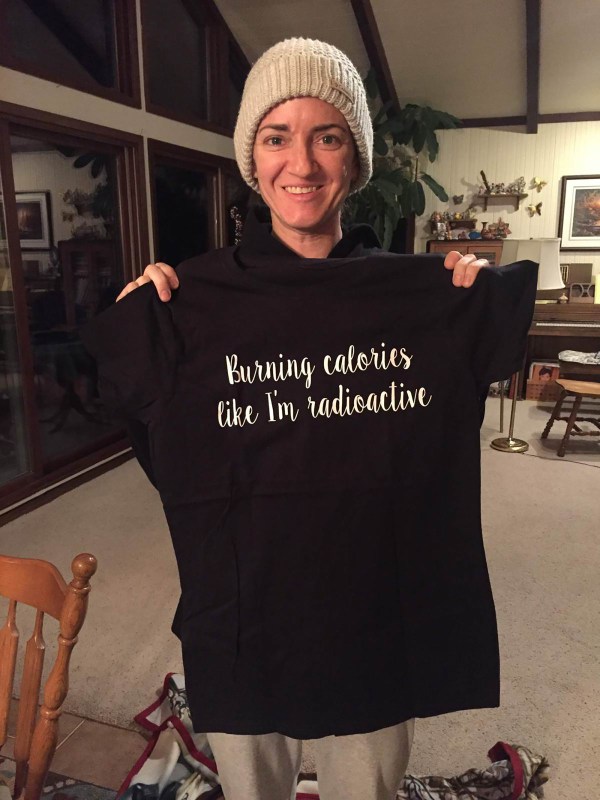

I was shown so much love while I sat in the basement. My mom delivered food to the stairs. Friends dropped off bags of cookies and stacks of books and chatted with me on the phone and mailed me fuzzy slippers and T-shirts that read, “Burning calories like I’m radioactive.” Which I was. People I didn’t even know by name prayed for me.

Courtesy of Rachel Jones

Courtesy of Rachel JonesBut for that limited amount of time, I couldn’t actively love them back. I couldn’t send them mail; my hands would have leaked radioactivity onto the cards. I couldn’t bake for them. I couldn’t do their laundry or run errands. I could only receive love —which was incredible. But it struck me that part of love is the ability to express it in return. And it struck me that those outcast by disease lose out on the opportunity to return affection, to love back.

When Jesus healed people, yes, he healed their bodies. But he also healed their place in society, their ability to love back and to serve others. He restored their ability to bake bread for a neighbor, to hold a crying baby so the new mother can rest, to invite a traveler into their home.

It can be tempting in our Western individualism to consider our faith so personal that we fail to appreciate this mutuality. Jesus came and restored more than individual bodies. He died to purchase more than forgiveness for individuals’ sins. He secured more than my singular hope for future paradise.

Jesus restored communities. Forgiveness is for corporate, generational brokenness. Heaven is the restoration of all things, the earth made wholly new. The Incarnation is Word made flesh and dwelling among bodies. This means the full gospel, the good news of the kingdom of God, is not just for me and not just for you. It is for us, the body of Christ, filled with the Spirit, worshiping God, together.

I think we are starting to sense that reality, as our spirits fill with eager anticipation and longing for the day when the curfews are lifted and the quarantined are set free. Imagine the joy! The intimacy of a hand on your shoulder. Hugging your grandmother, squeezing your chubby baby nephew, sharing a meal with neighbors, joining an all-office dance party.

My hope for those impacted by coronavirus, which is all of us, is what Jesus offered the lepers. Full individual healing and full corporate restoration of communities. That we will soon —Lord, may it be soon!—experience the good news of the gospel through the power of touch and of being touched, of love and of being loved —relationships restored and love reciprocated.

Rachel Pieh Jones works and writes in East Africa. She is the author of Stronger than Death : How Annalena Tonelli Defied Terror and Tuberculosis in the Horn of Africa and writes the “Stories from the Horn” newsletter.