I’ve come to depend on the University of St Andrews’s time-honored graduation ritual to give sense and order to my academic year. The wearing of gowns, recitation of Latin, and tapping of heads with an ancient cap, these have no intrinsic value. But each year, the principal of the university begins by explaining their meaning, and, infused with renewed significance, the ceremony transforms graduands into graduates.

Graduation is canceled this year due to the pandemic, so alternative means must mark the occasion. Physical presence is important but has never been required—plenty graduate in absentia and receive their diplomas on the authority of the principal’s words.

What happens, though, when ritual requires physical presence?

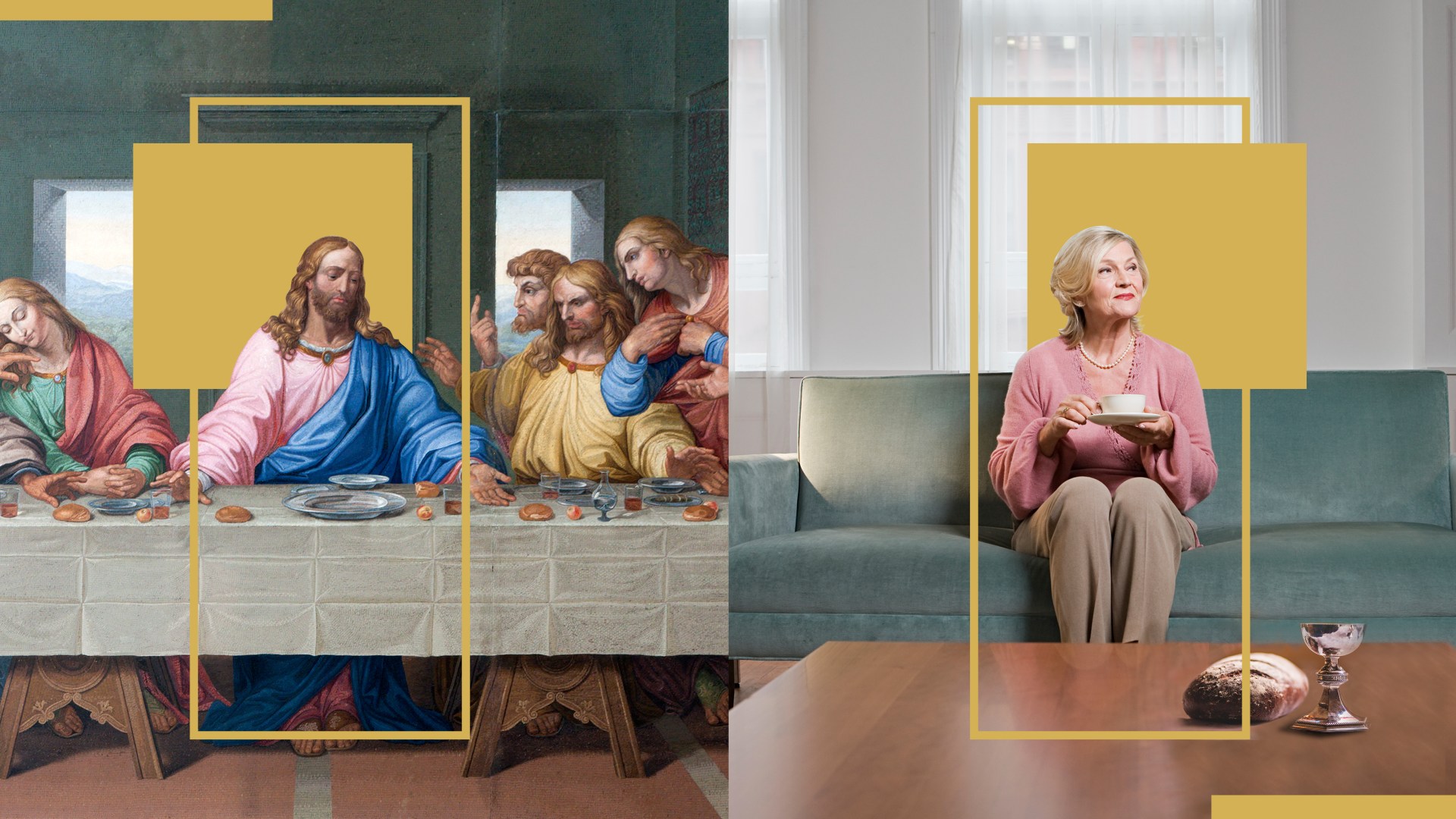

Christians are poignantly confronting this question during Holy Week. On Maundy Thursday, we traditionally gather to recount the Last Supper and re-enact it by sharing Communion. But during a pandemic, absence alters the ritual.

The Passover

Jesus’ Last Supper with his disciples was a Jewish Passover—a meal always commemorated in person. Passover was a pilgrimage festival, meaning that Jews traveled from all over to Jerusalem to celebrate.

The original Passover was God’s opening act of redemption (Ex. 12). Israelites smeared sacrificial lambs’ blood on their doorposts to be spared from judgment and ate hurried meals from the roasted meat with unleavened bread and bitter herbs. Then God led his liberated people out of Egypt through the wilderness to worship at Mount Sinai. At first, they worshipped remotely. God descended onto the mountain in a terrible thundercloud, and Moses constructed a crowd-control barrier to keep people from deadly judgment (Ex. 19:10-15). But God lifted the barrier with a covenant: Moses read out God’s commands and dashed sacrificial blood on the altar and on the people, saying, “This is the blood of the covenant that the Lord has made with you” (Ex. 24:8).

The sacrifice worked because God infused the ritual with meaning and power. According to Leviticus, blood symbolizes the force of life (Lev. 17:11). Thus, blood and the fatty portions of sacrificial animals ritually applied to the altar as God prescribed achieved atonement (see Leviticus 4). At Sinai, blood applied to the people bound them to God in covenant relationship. Through this ritual, blood was like a powerful detergent to remove the stain of impurity and sin, and God transformed unclean people into his holy own. Consequently, the dark thundercloud gave way to a clear blue sky: Israel’s leaders saw God and worshiped with a shared meal of sacrificial food at the foot of the divine throne (Ex. 24:10-11).

The food and drink flanking Israel’s founding moment marked God’s mercy and presence among his people. They were to keep the Passover perpetually as an embodied and communal ritual because the meal recalled the sacrifice that secured their life and liberation. Children asked its meaning, and parents retold the old, old story of God’s redemption (Ex. 12:25–28).

Israel was required to celebrate the Passover at the temple on the 14th day of the first month (Deut. 16:1–7). But God graciously allowed a makeup day in the second month to include those left out due to geographical distance, ritual impurity, or poor planning (Num. 9:9–13; 2 Chron. 30:1–3, 15–20). Keeping the Passover was crucial, so unnatural circumstances inspired new ways for people to be physically present.

Nevertheless, Israel’s Passover celebrations were patchy at best. The people forgot God’s redemption; sought emancipation; and ultimately, irrevocably, broke the Sinai covenant. God abandoned the temple and exiled Israel from the land. By the time of Jesus, the people had returned, but God had not. So, John the Baptist called Israel back to the wilderness, to reenact their founding Red Sea moment in preparation for a new covenant.

At his last Passover, Jesus sealed the new covenant with his own sacrificial blood. He presided over the table with his disciples and retold the old, old story, but with a new twist. Holding the bread and the drink, he recited Exodus 24:8 to make sense of his pending death: “this is my body … this is my blood of the covenant, poured out for many” (Mark 14:22, 24). Matthew includes “for the forgiveness of sins” (26:28) and Luke “this is the new covenant in my blood” (22:20). Jesus himself became the sacrifice on whom his disciples feasted, the shared meal a physical mediation of God’s new redemption (John 6:53–54). His explanation of the Passover ritual infused his actions with new meaning and the power to transform sinners into a community of saints.

Yet this Last Supper is ultimately realized in another meal. Jesus anticipated a great banquet where he will eat and drink with his followers anew—after his death and resurrection—in God’s presence (Matt. 26:29). Food and drink flank this new founding moment to join the whole of Jesus’ atoning work—his life, death, resurrection, ascension, and exaltation. Paul captures the anticipation to mark our celebrations: “whenever you eat this bread and drink this cup, you proclaim the Lord’s death until he comes” (1 Cor. 11:26, emphasis added).

Communion During Social Distancing

When we cannot be physically present with each other, technology can mediate to connect us virtually as one body for Communion. Author Deanna A. Thompson writes,

… [C]ommuning together virtually with our faith communities can affirm the reality that our bodies are engaged in worship even when we’re participating from our living room, that we’re still connected to the other bodies gathered virtually for worship even when we can only see photos of them online, and that Christ comes to us in the gifts of bread and wine even when our pastors’ Words of Institution are mediated by a screen.

Virtual Communion, while not ideal, may be permissible in an unnatural time. Alternatively, this unnatural time may provide an opportunity corporately to fast from Communion in anticipation of a makeup day. Like the first Passover, Jesus’ Last Supper was borne out of darkness, chaos, and uncertainty. So in our fasting, we might reflect, pray and lament for those who struggle and endure loss.

In any adaptation, we should stoke our appetites by hungering and thirsting for the real thing, like Jesus did.

And when we are all together again, we can throw a party.

Dr. Elizabeth Shively is Senior Lecturer in New Testament and Director of Teaching, University of St. Andrews, Scotland. She serves as a theology advisor for Christianity Today.