Dickson Mulli had just returned from a trip to the US and was working at his office in Nairobi when the first case of the novel coronavirus entered the country on March 12. Within days, the government ordered schools to shutter and nonessential workers to work from home. Within weeks, roads leading in and out of the city were closed.

While Mulli was concerned for his wife and one-year-old son, he also worried about the other people he was responsible for feeding: 3,500 former street children rescued by his father Charles’s nonprofit and hundreds of employees.

“When you have all these children and there’s a pandemic, and the roads and the markets are closed, what do you eat, and what do you do?” Mulli said. “During a pandemic, it’s back to basics. It doesn’t matter what kind of car you drive—you need food, you need peace of mind, you need good health—and of course, Jesus.”

Around the world, many children’s homes have been forced to close—for the best, some argue—since they could not guarantee the children’s health or care during COVID-19. But Mully Children’s Family (MCF) has not only been able to house, feed, and educate the hundreds of children in its care, it has also kept them safe and counseled them through the anxieties of an uncertain year.

Mulli—also spelled Mully in Kenya—estimates that in over 31 years, around 23,000 children have come through MCF’s various residential facilities. The organization has become a darling within some Western church circles, a model tale about a Kenyan man investing his life to help Kenyan youth. MCF has in recent years become more self-sustainable and built partnerships with Western funders.

MCF leaders, however, say they are now facing the greatest test in their organization’s history: seeing whether all their preparations and plaudits will be enough to endure a pandemic.

C

harles Mulli grew up as the oldest of ten children in a small village in Machakos County, Kenya. His mother and his father, an often-violent alcoholic, worked as farm hands to provide for their family. But when he was six, Mulli’s family abandoned him to find better work, leaving him in the care of an aunt. “I lived on begging from people house to house; it was terrible,” he said. He finished primary school (eighth grade) at age 17 but never proceeded to secondary school, unable to pay the school fees.

“The only difference between me and the present-day street children is that I never roamed around in town streets or sniffed glue,” Charles wrote in his memoir, My Journey of Faith. “Still, I had many similarities with them. I regularly begged for food from neighbors and wandered a lot in the village, to the point that I became a nuisance. . . . I chose to be ashamed and embarrassed rather than to die of hunger.”

Determined to make a life for himself, 18-year-old Charles walked the 70-kilometer journey to Nairobi, where he knocked on doors and asked around for work until he secured a position doing housework in a wealthy businessman’s home. The abandonment and abuse by his father sowed seeds of bitterness and anger in young Charles’s heart. By his late teen years, he contemplated taking his own life. But an acquaintance invited him to church. Despite his irreligious background, Charles found Jesus—and was suddenly filled with new purpose.

Over time, Charles rose into management at the man’s agricultural company and eventually started his own company, Mullyways—providing transportation between the capital and local villages. Business boomed; he diversified his entrepreneurial endeavors to oil, gas, and real estate and eventually purchased 50 acres of land in the Ndalani region for future retirement.

But one day on a business trip, Charles was approached by a group of street children who asked to watch his car in exchange for money. He ignored them. Later, he returned to discover that his car was gone. Forced to ride home via bus—possibly one of his own—Charles fell into an existential crisis that haunted him for three years. Why had he ignored the street children? After all, they were just like him! In November 1989, he felt the overwhelming call to leave his companies behind to rescue street children. It was a transformational day.

“ ‘You will never let my children suffer. You have to rescue them and become the father to the fatherless,’ ” Charles said he felt God telling him. “[That] was a big day for turning completely around. I was 40 years old. The following day, I went to the street.”

Charles and his wife, Esther, already had eight children—seven biological children and Charles’s adopted younger sister. They took in three more kids from the street in 1989. Six years later, they were caring for 300.

Today, MCF’s six campuses house or reach roughly 3,500 children.“I went to the street with one purpose: to rescue children. Every child needs food, love, accommodation, education, protection, [a] good and bright future,” Charles said. “Who then will reach to them with that love of Christ? I was one of them, one who is lost.”

Initially, he funded 100 percent of the children’s care from the sale of his businesses; when the money dried up, Charles sold his properties to support his rapidly growing “family.” Now, MCF relies on a combination of farm production and fundraising from chapters in Canada, Germany, and the US. Some donors also sponsor individual children.

Charles’s story—a homegrown leader rising from poverty to tackle his own country’s problems, in contrast to outsider intervention—has inspired Western Christians and donors. It has spawned two biographies and a feature-length documentary about “the world’s largest family.”

“Every child needs food, love, accommodation, education, protection, a good and bright future. Who then will reach to them with that love of Christ? I was one of them, one who is lost.” – Charles Mulli

“It’s not 100 percent foolproof, but the local solutions are a good one; local leadership is a success, rather than a patriarchal approach,” said Wheaton College director of humanitarian and disaster leadership Kent Annan. International aid experts often favor employing local leaders to solve humanitarian problems, since locals are familiar with their own contexts and are accountable to their own communities.

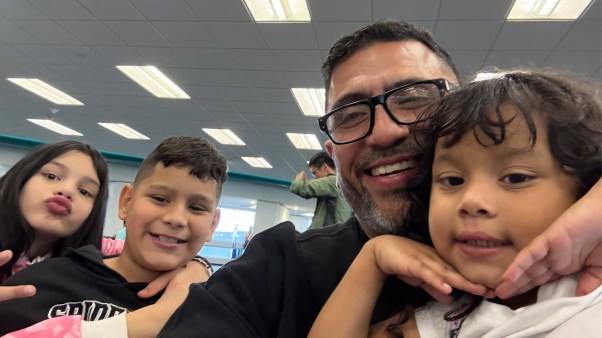

“What my dad once told me—when I asked him why he does what he does or does he enjoy serving the children—he told me he enjoys serving God more,” Dickson Mulli said. “Because when he serves God, he serves the children. When he loves God, he loves them like God intended him to love the children. And when you focus on Christ, then you can be able to fulfill his purpose in other people’s lives.”

T

he bone-jarring road down to Mully Children’s Family in Ndalani winds through a landscape of rocky, steep hills. “Daddy Mully,” as he is affectionately called, is easily identified on the MCF campus with his trademark wide-brimmed leather hat and his frequent, optimistic smile. It’s the tender smile of a father who wants the children to see themselves as part of the Mully family. While his biological children all assist in major decision-making at MCF, six of them still work there full time.

“There’s a satisfaction that comes with helping someone meaningfully in a way that will transform their lives and in a way that they will not repay you back,” said Dickson, Charles’s youngest child and director of MCF’s sustainability projects. His wife, Mary, is a graduate of MCF and runs its child sponsorship program. “That satisfaction is what keeps me working.”

Photo by Tonny Onyulo

Photo by Tonny OnyuloMCF’s goal is to meet the essential needs of each child: food, shelter, education, medicine, and love. It also offers services like counseling and rehabilitation for former sex workers.

MCF’s six locations scattered around Kenya each serve a different purpose. Fifty-eight kilometers from where Mulli roamed the village streets, the charity now houses nearly 850 children from birth to age 22 in Ndalani, its largest campus and agricultural center, where many teachers and staff also live. Here, students attend school in the morning and play soccer and enjoy other recreational activities in the afternoon.

Nearby, in Yatta, another children’s home separately cares for 200 child mothers and 90 babies as a safe rehabilitation center for abused girls and those who were rescued from prostitution or child marriage. Similarly, the MCF campus in Kilifi County—about 100 kilometers outside the city of Mombasa—offers a daycare and school for nearly 300 children, many of whom were rescued from child labor or sex tourism.

Eight hours northwest of Ndalani in the highlands, MCF Eldoret houses children under the age of nine. Two other locations in the country provide community outreach such as daily meals and education—one for 250 children in the Kipsongo slums, and one for around 850 children in Lodwar, including Sudanese refugees.

“Many people in Kenya think of me as a stupid person. They think I am a fool,” Charles Mulli wrote in his memoir. “I am bringing tribes together. But in the African mindset, I am supposed to concentrate on my own tribe and build up only them. What I do is contrary to what other people think I should do.”

Like other children’s homes in Kenya, MCF uses a family model to rehabilitate children and grows crops to supplement its outside support. Many of these homes are known officially as Children’s Charitable Institutions. They may function as miniature villages or shelter children in dormitory-style settings and offer education, food, and clean water.

What makes Mulli’s endeavor unique is its scale and its pursuit of self-sustainability, as well as its work to solve the systemic problem of child homelessness by caring for the local community, said Reuben Langat, the US director of partnerships at Missions of Hope International. A Kenyan and former pastor, Langat visited MCF in 2011 and 2012 while learning how to start his own home for street children. (He also helped found Africa Gospel Church Baby Centre, an orphanage for adoptable babies in Nakuru, Kenya.)

“Mulli involved other people from the community, and volunteers could come and visit and support MCF,” Langat said. “The graduates who went through the home became good alumni. That network over time has become a good resource.”

The ability to feed the children off the farm is also an advantage, Langat added. “The challenge comes when a home depends only on Westerners for support.”

Photo by Tonny Onyulo

Photo by Tonny OnyuloI

n 2013, the United Nations reported that there were more than 100 million street children around the world, mostly in Africa and parts of Asia. While data is hard to come by, UNICEF estimated in 2012 that around 300,000 children lived on the streets in Kenya, with about 20 percent of those in Nairobi alone.

“The main drivers to the street are poverty, conflict, and child abuse,” according to University of Toronto professor Paula Braitstein, an epidemiologist who has been studying the well-being of street children and children’s homes for more than a decade. On the streets, children face higher rates of premature mortality, pregnancy, abuse, hunger, HIV, and other illnesses—never mind societal stigma.

COVID-19 has exacerbated these risks. While the Kenyan government has made some efforts to get children off the streets, Braitstein presumes that many street youth are likely threatened with jail when they have nowhere else to go.

Although children on the street face immense challenges and trauma, not everyone sees children’s homes as beacons of hope. Many nonprofits like MCF are facing global scrutiny. As the coronavirus pandemic picked up, nearly 20,000 orphans in Kenya returned home after their orphanages closed. That has raised questions about whether institutions should be housing children who have living family.

As Ade Olowo, the coach for African churches for the Christian Alliance for Orphans, put it: “If the kids have families, then why are they in the orphanages in the first place?” And, he wondered, will the pandemic make people think twice before sending kids back to children’s homes?

In 2017, UNICEF estimated that about 40,000 Kenyan children lived in more than 800 registered children’s homes, and it’s believed that about 80 percent of those children have at least one surviving parent. About half of the children MCF houses are parentless, according to Charles. The others have one living parent or come from street families.

One such beneficiary of MCF, Stella Louko, was picked up by Charles Mulli in July 2002 from the streets of Kitale after she escaped her single mother’s drunken verbal and physical abuse at a young age. “Compared to the street, [MCF] was a palace to me,” she said. “When I joined the home, I felt parental love and I got my basic needs met. I really thank God for everything.”

Even though Langat has started two children’s homes, he believes that family care is the ideal model for children who have families. When his team screened street children to learn about their needs and family situations, he discovered that many of them had at least one parent but were forced onto the streets due to extreme poverty. “We discovered that helping those families improved their lives in terms of farming or do[ing] business,” Langat said. “Helping families helps their children.”

Abandoned children in tightly knit rural communities often do receive some care from neighbors or extended family, Langat said, but “urban areas are a different story.”

Olowo also works with churches and local government agencies to advocate for family care, but he sees the role that quality institutions like MCF play in African societies.

“Orphanages and children’s homes are very important,” he said. “Most pastors know this is the right call [to help street children], but the question is how do we do that. . . . An African church might once a year buy food and take it to the orphanage, but they’re not seeing what is the kids’ story and how do we work with them. We’re having discussions about the systemic problems and how churches can step in to help.”

M

any children’s homes, which depend heavily on funding from the United States and other wealthy countries, have seen drops in donations since the pandemic began impacting the global economy, according to Paula Braitstein.

And Kenya’s economy has not been spared.

“This is an eight-month-plus disaster that people are facing while already working on a shoestring budget caring for a vulnerable community,” Wheaton College’s Annan said.

Courtesy of Mully Children's Family / Facebook

Courtesy of Mully Children's Family / FacebookAs of late September, Kenya had reported about 37,500 known COVID-19 cases in the country and 669 deaths, the second highest count among East African countries yet still relatively low compared to global rates. Yet the horticultural sector in Kenya “lost half its exports, half its value, and laid off most of its workforce of 75,000,” wrote William Mark Bellamy, senior adviser for the Africa Program of Center for Strategic and International Studies, in June. Around 50 percent of Kenyans were either laid off or furloughed, he said.

MCF was impacted similarly. Its campuses immediately closed down, banning visitors and employees who lived off site. While some employees chose to move onto campus and continue working in order to feed the children, their responsibilities multiplied to cover for missing workers. Dickson’s employees dropped from 500 to 78. Agriculture production slowed. Some staff went without pay. The schools closed, though some Ndalani teachers opted to live on campus and teach a half day. Charles had to figure out how access more water to provide for increased hand washing.

It was a catastrophe unlike any he’d seen, Charles said. “Because we keep orphans, street children, children who have nowhere to stay, this is their home.”

“We were trying to follow government regulations but also needed to feed the children,” Dickson added. “March and April were really difficult.”

But food and finances were only two of their fears. Some of their children suffer from HIV and diabetes. If the virus had entered one of the campuses, it would “have spread like wildfire,” Dickson said.

Much of the staff’s job was comforting the children and repeating the mantra heard around the world: “Wear a mask and wash your hands.” The young women staying at Yatta sewed masks for the hundreds of children in their care under the watchful eye of Esther Mulli. Now, the children run around campus with homemade cloth masks hanging from their necks. They have learned to wash their hands frequently from tubs of water at school and in the dining hall.

“When you have 3,500 children, they look at my parents as their parents and MCF as family,” Dickson said. “We had to assure them, because there was a lot of panicking.”

The pandemic has taught MCF a lot about safeguarding its community and what it means to be part of a giant family, Charles said. So far, he knows of no child, parent, or guardian related to MCF sick with the coronavirus. “Yes, this was a serious attack,” he said. “But we have been protected.”

Dickson sees the hand of God in the midst of the financial struggle. When the pandemic began, he said he turned from worry and despair to seeing the pandemic as an opportunity to pray, love, and “tap into the Holy Spirit.” He compared MCF’s years of investment in horticulture to the story of Joseph in the Old Testament, who interpreted Pharaoh’s dream to predict seven years of plenty in Egypt before seven years of famine.

“You don’t know when you’re doing something [necessary for the future],” Dickson said. “When the drought came during the time of Joseph, the seven years of plenty were important. Now in the pandemic, the fact that we were always doing production of food and being self-reliant in one way or another was a blessing from God.”

Still, as it has done for other ministries around the world, COVID-19 has pushed MCF to lean on faith.

“We know God will provide,” Dickson said. “But this is one of those moments when he really needs to come through.”

Kara Bettis is an associate features editor with Christianity Today. Tonny Onyulo is a freelance print and broadcast journalist based in Nairobi, Kenya.