Mark Lanier thinks if you were going to fake a fragment of the Dead Sea Scrolls to sell to an unsuspecting evangelical collector, you wouldn’t pick Amos 7:17.

Psalm 23, maybe.

Or Jeremiah 29:11.

Even Proverbs 3:13.

But not Amos 7:17, which says, “Your wife will become a prostitute in the city, and your sons and daughters will fall by the sword.”

Except maybe that’s exactly what a forger—trying to pass off a scrap of distressed leather as an ancient bit of the Bible preserved in desert caves for two millennia—would want you to think. So in 2013, Lanier made sure an antiquities dealer had legal documentation of the authenticity of three pieces of the Dead Sea Scrolls before he bought them to donate to the Lanier Theological Library in Houston.

“We passed up purchasing a number of other fragments on this issue,” said Lanier, a Texas trial lawyer and philanthropist. “We did due diligence and were assured of the provenance.”

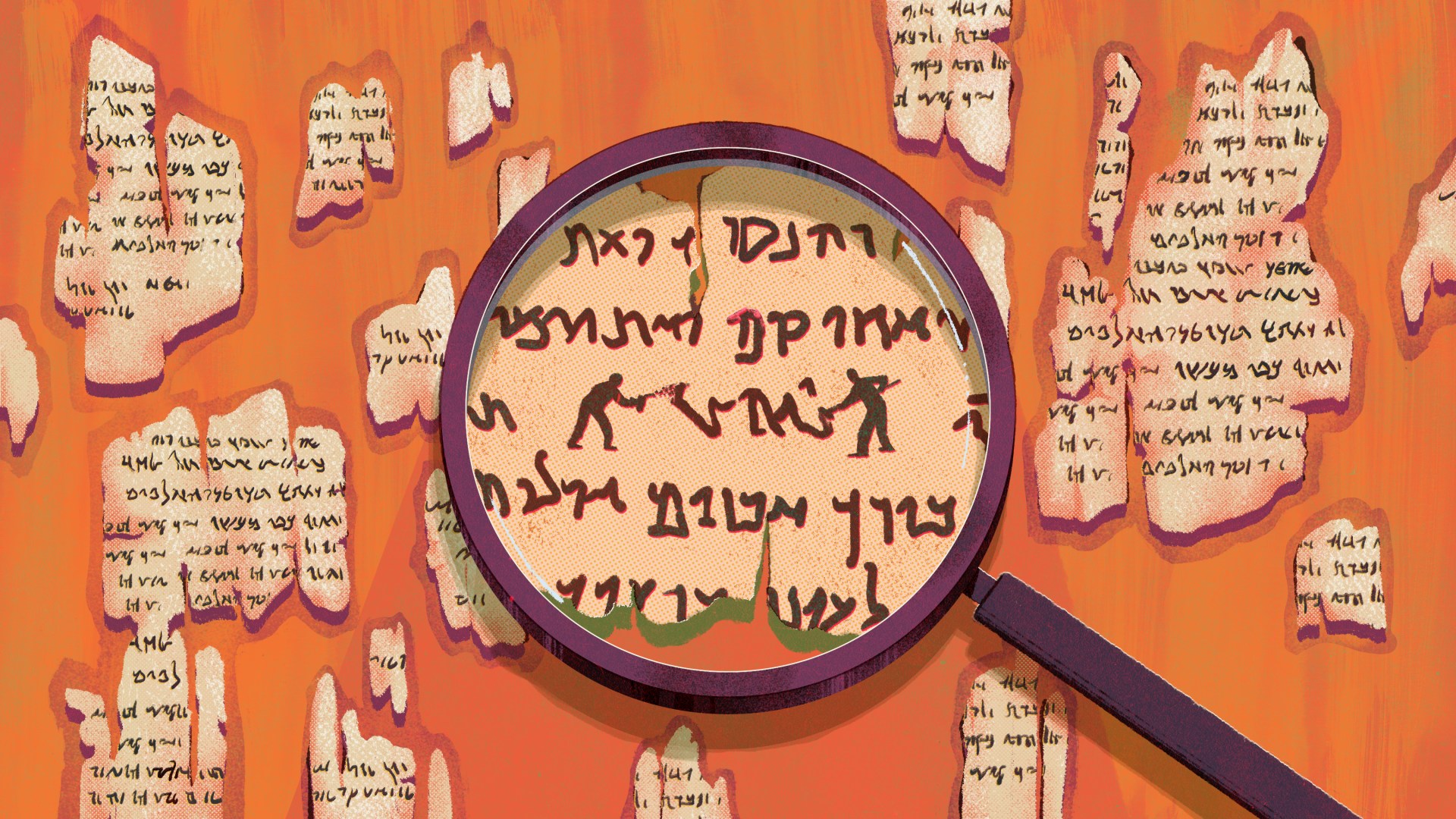

A shadow of suspicion has spread across antiquities collections at US evangelical institutions in recent years as a small team of Dead Sea Scrolls detectives has raised concerns about modern forgeries. The Museum of the Bible reported that all 16 of its prized fragments were fakes, and experts wonder: How many more are out there?

More than 70 pieces of the Dead Sea Scrolls have been offered for sale on the antiquities market in the past two decades. It seems unlikely a criminal would produce and sell 16 forgeries and then just stop.

“Whoever was manufacturing these was responding to the market,” said Kipp Davis, an expert in biblical archaeology and Dead Sea Scrolls forgery. “That market was, for the most part, wealthy evangelicals.”

The Museum of the Bible purchased Dead Sea Scroll fragments in four different lots from four different dealers between 2009 and 2014 as part of its push to collect the most important artifacts from the history of Bible. The scrolls are “the most significant archaeological discovery of the 20th century,” according to Jeffrey Kloha, the museum’s chief curator. They are important to the museum’s mission to tell the story of the sacred text.

The museum invited a team of scholars to study them. When the scholars started to examine them closely, they noticed some of the fragments didn’t look right.

“They looked like they had been written by unpracticed scribes, or scribes who weren’t very good,” said Davis, who was part of the team.

The museum decided to have all 16 tested by Art Fraud Insights. Under the microscope, experts saw that the text had not been written on fresh parchment, which then decayed over time, but on old leather, distressed to look like it was an ancient manuscript. Colette Loll, CEO of Art Fraud Insights, said the ink going into the cracks and over the broken edges was a telltale sign.

The museum announced the findings in March and apologized for poor judgment in building its collection. It launched a new exhibit displaying the forgeries in October, which tells the story of one of the most amazing archaeological discoveries of the 20th century—and a still-unfolding story of greed and deception.

Scholars praised the museum for its transparency. Other evangelical institutions, however, were left wondering about the legitimacy of their own collections of Dead Sea Scrolls artifacts. All of these collections, built in the past few years as new fragments came up for sale on the antiquities markets, now had red flags, according to Davis.

For example, only about a quarter of the fragments found in the caves around the Dead Sea in the 1940s and ’50s contained biblical texts. The majority were copies of texts from the expanding literature of Judaism in the Second Temple period and the community that lived at Qumran. But the fragments that have appeared for sale in recent years have all featured portions of the Bible.

They were not the passages a Christian would most likely choose for a life verse, but they were Scripture nonetheless: 1 Kings 13:22, Isaiah 28:23–29, Joel 3:9–10, and Amos 7:17.

Lanier checked the documentation of the provenance of the fragments at Lanier Library again to reassure himself.

Documentation can be fraudulent, but it creates a legal responsibility for authenticity. Azusa Pacific University has concluded the five fragments it bought for $1.3 million are probably not authentic. The school is suing the book dealer who brokered the sale.

Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary considered investigating its eight fragments, which it bought with the help of two major donors in 2012, but decided against spending more money on independent authentication. The school recently closed its archaeology program as part of an “institution reset” with a change in administration.

“The fragments are in a secure location and have not been available to the general public in some years,” the seminary said in an official statement. “We would welcome an independent investigation of the seminary’s fragments, although . . . it is not prudent for the seminary to spend further precious funds on them.”

Loll said Art Fraud Insights is doing a number examinations of scroll fragments for worried collectors.

“The only way to really be certain that they are genuine is to, of course, put them through the kind of rigorous testing that the Museum of the Bible did. But that’s expensive,” said Sidnie White Crawford, antiquities expert and professor emerita at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln.

Scholars continue to make discoveries studying the original Dead Sea Scrolls fragments. Earlier this year, the University of Manchester in England announced that some of its seemingly blank pieces—donated to scholarship by the Jordanian government in the 1950s—actually contain words, possibly from the first verses of Ezekiel 46.

For now, though, scholars will have little interest in fragments sold after 2002. And evangelical collectors will be wary of buying any more bits of the Dead Sea Scrolls without having them thoroughly tested. This is expected to have a serious impact on the market for ancient Bible fragments.

Some experts hope the Bible museum’s discovery of fraud will kill the market altogether.

“People should not buy antiquities,” said Christopher Rollston, a forgery expert and professor of Hebrew at George Washington University. “Never buy anything on the antiquities market; it just creates incentives for pillagers and [unscrupulous] dealers.”

Gordon Govier is the editor of Artifax magazine and writes about archaeology for Christianity Today.