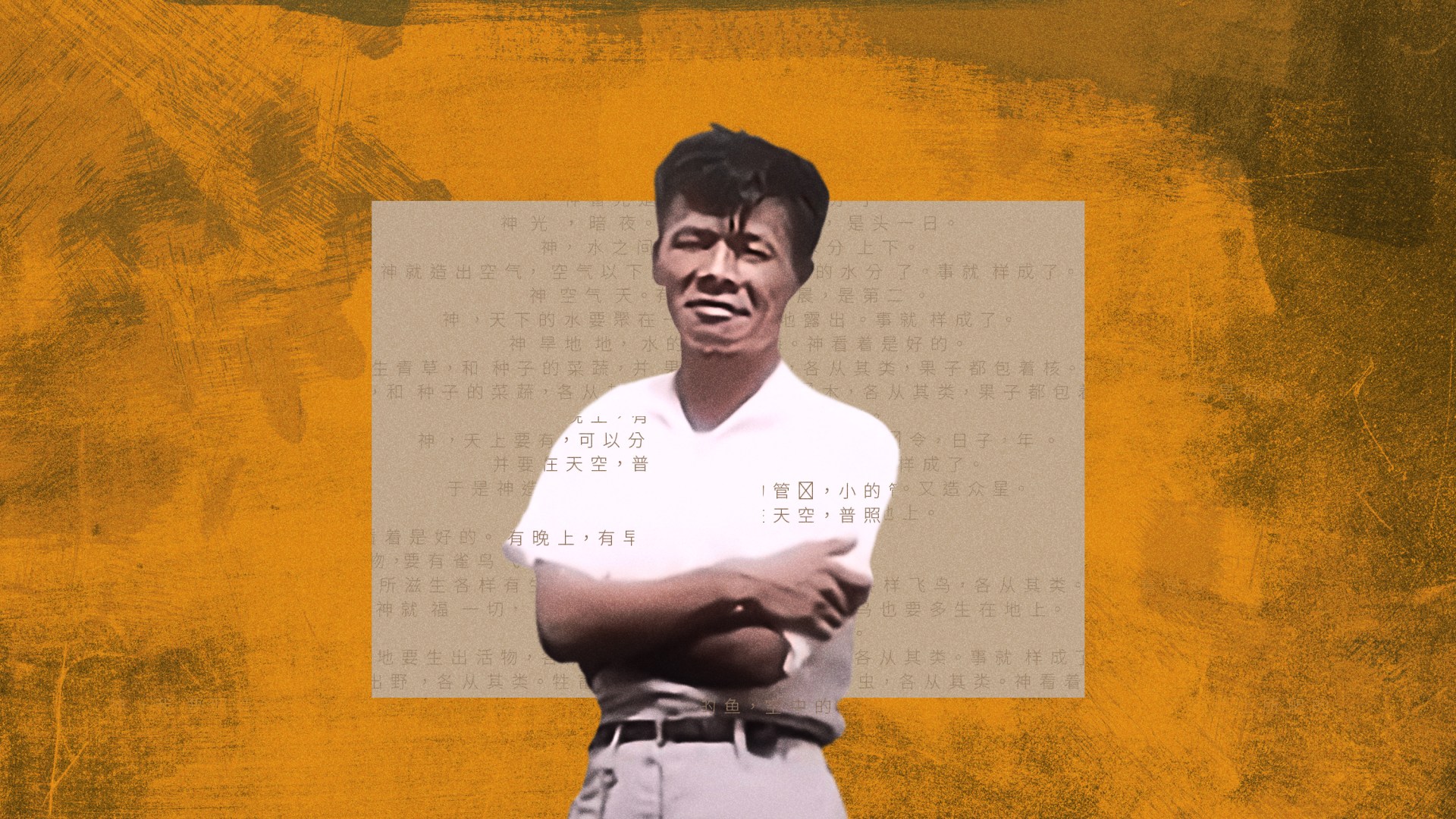

The story of John Song is fairly well-known within the history of Chinese Christianity. In 1920, he left China to study chemistry in the United States, completing a bachelor’s degree in three years and a master’s degree and a doctorate in another three years. He then turned to theology and enrolled in America’s leading institution of liberal Christianity, Union Theological Seminary in New York City. He had an evangelical conversion experience—but seminary authorities thought he was mad and sent him to an asylum. After his release in 1927, Song boarded a ship headed back to China and committed his life to preaching the gospel message.

John Song: Modern Chinese Christianity and the Making of a New Man (Studies in World Christianity)

Baylor University Press

268 pages

But there is another side to the story, one fleshed out in a new biography from Boston University global Christianity scholar Daryl R. Ireland. John Song: Modern Chinese Christianity and the Making of a New Man presents a brilliant student living with schizophrenia—one who saw visions, spoke as a prophet of a new age, and decoded divine messages in New York Times crossword puzzles and through “radio schematics” in the four Gospels. At one point, he supposedly fell in love with a supernatural being and married her in the presence of 7,000 honorary queens.

Ireland’s access to previously un-available materials—Song’s student files at Union and some 6,000 pages of personal diaries—enables him to paint a very complex picture. From this basis, Ireland argues that the seemingly divergent accounts of Song’s American background converge into one: the making of China’s greatest evangelist. They are the origin stories of a new man.

When Song returned to China, he was disgraced by his expulsion from Union and his hospitalization for mental instability. Things changed when he met the fundamentalist Methodist Episcopal missionary W. B. Cole. According to Ireland, Cole saw in Song an opportunity to condemn Union for its modernist theology, while Song saw in Cole an opportunity to reinvent himself. Together, they crafted a new account of Song’s troubled past: As Ireland sums it up, “Song had encountered the God made known in Jesus Christ at Union Theological Seminary, and he was rejected because of it.”

This new beginning was key to Song’s revivalist message going forward, just as new beginnings were key for China in the 1920s–1940s, when reformers hoped to escape the country’s feudal past in pursuit of new culture, new life, and a new China.

Song was now a new man—in terms of evangelicalism and modernizing China. For instance, the Nationalist government tried to purify religion by launching the Smashing Superstition Movement in 1928. That same year, Song began his career as a traveling evangelist for the Methodist Episcopal Church, in which he preached a message that Ireland describes as being “tested by spiritual life and science.” With a PhD in chemistry, he had the credentials to defend faith as something more than a superstition that science was smashing.

Song renewed himself time and time again. Initially, when he preached in rural villages, his sermons focused on how the supernatural world penetrated the natural world. After 1931, when Song joined the Bethel Worldwide Evangelistic Band to tour around China’s urban centers, his preaching transformed into a new expression of Holiness revivalism. When his relationship with Bethel ended in 1933, Song again rewrote his sermons to address sectors of society that he had not previously encountered.

Two of Ireland’s final chapters address important themes of early-20th-century China. The first highlights how Song’s preaching was particularly appealing to women. Men and women needed more than just to be saved—Song called them to organize their own evangelistic teams. Vast numbers of women took up this call. Song was offering an alternative to Confucian gender roles and to the secular-feminist vision developing in China at the time.

Likewise, the final chapter covers Song’s divine healing ministry, which offered an alternative to both traditional Chinese medicine and Western biomedicine. In the end, Song’s healing hands were unable to heal himself, and he died in 1944 after years of dealing with an anal fistula.

Ireland advances a theory about Song’s reinvention as part of a larger story of Chinese Christianity’s 20th-century development. Even more, he teases out how Song and Chinese Christianity offered an alternative to the path of exchanging a feudal past for a modern future. This new man and this new religion profoundly influenced the making of a new China.

Alexander Chow is senior lecturer in theology and world Christianity in the School of Divinity at the University of Edinburgh. He is author of two books, most recently Chinese Public Theology: Generational Shifts and Confucian Imagination in Chinese Christianity.