[Read in Portuguese or Indonesian]

This is the fifth in a six-part series of essays from a cross section of leading scholars revisiting the place of the “First Testament” in contemporary Christian faith. —The editors

I am not an Old Testament theologian, but I have loved the Old Testament for a long time.

I had quiet times before I knew they were a requirement for Christian living, and during such times I found myself naturally and inexplicably drawn to the Old Testament. I would take my Bible and a journal—and sometimes a Bible study guide or a book of poetry—and lose myself in it all.

The Psalms in particular were amazing to me. They were full of the same rampage of emotions I was experiencing as an adolescent: anger and sadness, loneliness and questions, yearning and passion, worship and awe. When I was immersed in the Psalms, I felt understood and comforted—as if someone really got me. When I read David’s confessions of sin or his seething imprecations against his enemies, I knew there was nothing I couldn’t name in God’s presence. Nothing was out-of-bounds. For a passionate, melancholy young girl and pastor’s kid in a conservative religious environment, this was no small thing! The Psalms gave me a place to be and to breathe; I loved God because of what I experienced with God there.

I realize now that I was learning how to pray not so much from the teachings in the New Testament (valuable as they are) but from actually praying along with the great pray-ers of the Old Testament. To me, it wasn’t old at all; it was fresh and new. The psalm writers gave me words when I had none, jump-starting my own prayers. This was my earliest experience of being shaped spiritually by the Old Testament.

What Is Christian Spirituality?

What do we even mean when we talk about being “shaped spiritually”? The term spirituality is a rather ambiguous and ubiquitous term in today’s culture. If we listen carefully, we might hear it used to describe everything from meditation to mountain climbing, from the “flow” an athlete feels on the basketball court to the unselfconscious state of the artist caught up in his or her art, from going on a silent retreat to worshiping in a cathedral, from practicing yoga to simply paying attention to one’s breathing. The language of spirituality can seem like an ill-defined, amorphous, soft-around-the-edges sort of thing, signifying an otherworldly sentimentality with a bent toward the mystical that often has little to do with any deity or religious affiliation.

But let’s reclaim this term and put it to good use, shall we? Simply put, spirituality is all the ways in which human beings reach for God, for truth, for personal significance, and for ultimate meaning. All human beings have a body, soul, and spirit, and the spirit is what animates us. When the concept of spirituality is coupled with the word Christian, however, an even clearer perspective emerges. Bradley Holt, in his book Thirsty for God, clarifies that, in the Christian tradition, the term “refers in the first place to lived experience.” “If we live by the Spirit, let us also keep in step with the Spirit,” Paul writes in Galatians 5:25 (ESV). “The starting point is the Spirit of Christ living in the person,” Holt says.

Within a Christian framework, then, the words spiritual and spirituality signify being “of the Holy Spirit”—the third Person of the Trinity, the one sent by God at Jesus’ request to be our advocate and our counselor and to guide us into truth as we are able to bear it. As Philip Sheldrake argues in A Brief History of Spirituality, a “spiritual person” (1 Cor. 2:14–15) in Paul’s letters was simply someone the Spirit of God dwells in who lives under the influence of that Spirit.

By defining spirituality in this way, we home in on the significance of the root word spirit—a richly biblical concept referring to both the human spirit and the divine Spirit. The divine Spirit refers to the Spirit of God, who was active in human affairs in the Old Testament and is the Holy Spirit who dwells within us now. Thus, spirituality that is distinctly Christian is spirituality initiated, animated, and guided by the Holy Spirit. This imbues it with a certain gravitas that may be missing from more general and imprecise uses of the term.

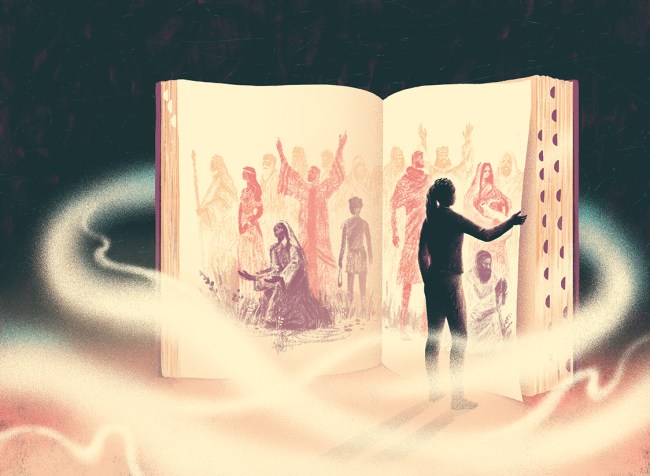

Illustration by Matt Chinworth

Illustration by Matt ChinworthPraying with the Old Testament

By definition, then, all of us have a spirituality—a way of responding (or not) to the Spirit that has been given. And while the starting point is the Spirit of Christ living within each Christian, we each have a particular style of Christian discipleship—or, as Dallas Willard put it, a particular way of being “with him to learn from him how to be like him.”

Different traditions, denominations, and religious orders embody and codify many of these distinctions in style. “For example Jesuits, Lutherans, and feminists each have a particular combination of themes and practices that make them distinctive,” Holt writes. “It is vitally important for Christian spirituality today that we take a wide view of that tradition and of the global family of Christians, not simply enshrining the small strand of tradition that may be familiar from our home, congregation, or ethnic group. The sweep of that tradition will open our eyes to wide resources of spirituality and give guidance for our own choices.”

If we can learn from the best of a diverse set of secondary resources, surely we can rediscover how the Old Testament—the majority share of Scripture—might shape Christian spirituality today.

Consider, for example, that prayer is a primary expression of our spirituality. The Westminster Dictionary of Christian Spirituality boldly states that “Prayer is more than pleading or petition: it is our whole relation to God.” My own definition is that prayer is all the ways we communicate and commune with God. We are formed in prayer by actually praying. Looking back on my early experiences with the Psalms, I realize that is exactly what was happening. I was being formed spiritually by praying with the Jewish prayer book—the very one Jesus and his disciples used as practicing Jews. What an amazing thought!

For the sheer comprehensiveness of prayer genres, the Psalms are unparalleled. There we find personal prayers and communal prayers, prayers of lament and prayers of thanksgiving, penitential prayers expressing profound humility and imprecatory prayers boldly calling down God’s wrath and judgment on sinners, spontaneous prayers and temple liturgies, doxologies that express great certainty and intimate prayers that express deep questions and doubts. No wonder historic Judeo-Christian practice includes reading and praying with the Psalms every day. If that were the Old Testament’s only contribution to our spirituality, it would be plenty; but of course, there’s much more.

An Invitation to Solitude and Silence

Those early encounters with God in the Psalms were, perhaps, my first experiences of having my spirituality—not just my theology—shaped by the Old Testament. But that wasn’t all. When I was in my early 30s, there came a day when words just weren’t working for me anymore and systematic theologies were not meeting my longing to really know God. In addition, I was seeking real change in my life, and the New Testament categories were just not resonating as they used to; in fact, the unbridled activism that characterized my evangelical upbringing had left me worn down and completely exhausted. So I dropped out, not even sure I wanted to be a Christian anymore.

The one thing I did know was that I wanted God more than I wanted to be a Christian (if that makes any sense at all), and that is when my story intersected with Elijah’s in 1 Kings 19. Here I encountered a person I could relate to—a spiritual leader who had come to the end of himself and his ability to sustain what life in leadership required. Following a great success (1 Kings 18), we find Elijah running for his life, having left everything and everyone behind, slumped under the solitary broom tree, asking God to take his life. This is the deepest kind of solitude, or interiority, and solitude began to do its good work, even though Elijah didn’t know much about it.

When I encountered Elijah, I had found myself in a similar situation internally, though the details were different. At the time, no one in evangelicalism was talking about solitude and silence. So when a spiritual director began guiding me into these practices, I needed a place in Scripture to land. I needed to know that what I was doing was within the bounds of orthodox Christianity, and the Old Testament showed it was.

Elijah’s story (not his pontificating) gave me the courage to let go and take my own journey into solitude and silence. I began cultivating solitude as a place of rest in God, just as Elijah had experienced. Over time, it became a place of encounter with God where I heard God’s questions for me, a place of peace where the inner chaos began to settle, and, finally, a place of attention where I could receive God’s guidance and wisdom for my next steps. None of this would have happened without Elijah’s story. Even though I was fully aware of Jesus’ time in the wilderness and its significance, something about the raw humanity of Elijah’s experience drew me in a fresh way.

Eventually, I returned to my life in the company of others and, as God would have it, I was drawn back into active ministry. As the demands and challenges of leadership intensified, I cried out to God for someone else from Scripture to walk with—someone who could help me make sense of what happens to leaders, why it has to be so hard, and how to be sustained for the long haul. And God, who is faithful, gave me Moses. In Moses’ story I found a detailed and deeply spiritual perspective on leadership that was second to none except Jesus himself. Somehow, Moses’ story seemed to include more of the human elements of the struggle to stay faithful, and I resonated deeply with his ups and downs and everything in between.

I wondered, How did he do that? How did he sustain himself for the long haul of ministry in the midst of such difficulty and relentless challenge? I noticed that Moses did not seem to have any great strategy for leadership. Instead, I observed a sacred rhythm that I began to feel drawn into. It was the sacred rhythm of encountering God in solitude and then emerging from that encounter and doing exactly what God instructed. For Moses, leadership was that simple, and I thought, Now that is an approach to leadership I can actually enter into.

There is so much more I could say about Moses’ companionship for my life as a leader. But suffice it to say that God has used the Old Testament narrative of Moses’ life to turn the experience of leadership inside out so I could see what it looked like and what was really involved in being strengthened at the soul level in an ongoing way.

Show, Don’t Tell

In my experience, the Old Testament narratives externalize that which is deeply internal, extremely personal, and even somewhat mysterious about the spiritual life. They show rather than tell what it is like to encounter the living God in the midst of our ordinary lives and what happens when we respond. They illustrate what it is like to cultivate a real relationship with God that may even involve arguing with God until God gets mad at you.

David’s soaring praise and intense wrestling with God (captured in songs, poems, and written prayers) show rather than tell what it is like to be honest with God and indicate that God can take it. Elijah’s life-sustaining encounter with God illuminates the powerful results of solitude that simply do not come to us in any other way.

The Old Testament’s matter-of-fact recounting of Deborah’s role as prophet and judge in Israel at a pivotal moment in the nation’s history showed me that God can—and will!—use anyone God wants to do what needs to be done (Judges 4). As a young woman called to ministry, I desperately needed to see this. I also needed to be assured that there would be men like Barak who saw the value in partnering with women leaders and who were willing to share fully in the risks and rewards of walking together into dangerous territories and being met there by God.

Another example is Eli’s assistance to Samuel as Samuel grew in his ability to hear and respond to God (1 Sam. 4). This demonstrates the inestimable value of spiritual direction in the life of an emerging spiritual leader—a crucial biblical snapshot for my own sense of call. Eli’s realization that the voice in the night might be God calling the little boy, and then the way he guided Samuel to respond if it happened again, seemed to be one of the most valuable things one human being could do for another. And you didn’t have to be perfect to do it. Later, when I realized that this is exactly what spiritual directors do, I was filled with longing to sit with people in exactly the same way.

All of these stories turn individuals’ deeply personal experiences with God inside out, so we can see that which would otherwise be hidden from our eyes. They illuminate these experiences from the inside—inviting us to be open, receptive, and perhaps even expectant that these same things could happen to us. Then, when we stumble into such experiences, through no knowledge and foresight of our own, the Old Testament narratives help us find courage to lean in and say, “This must be what it’s like. Count me in!”

Ruth Haley Barton is founding president of the Transforming Center, a seasoned spiritual director, and author of Strengthening the Soul of Your Leadership: Seeking God in the Crucible of Ministry (IVP Books).

Have thoughts or comments about this article? Let us know!