In the courtyard of the headquarters of Overseas Mission Fellowship (OMF), across the street from lush botanic gardens in the city-state of Singapore, there is a pavilion emblazed with words in both Chinese and English: “Have faith in God.”

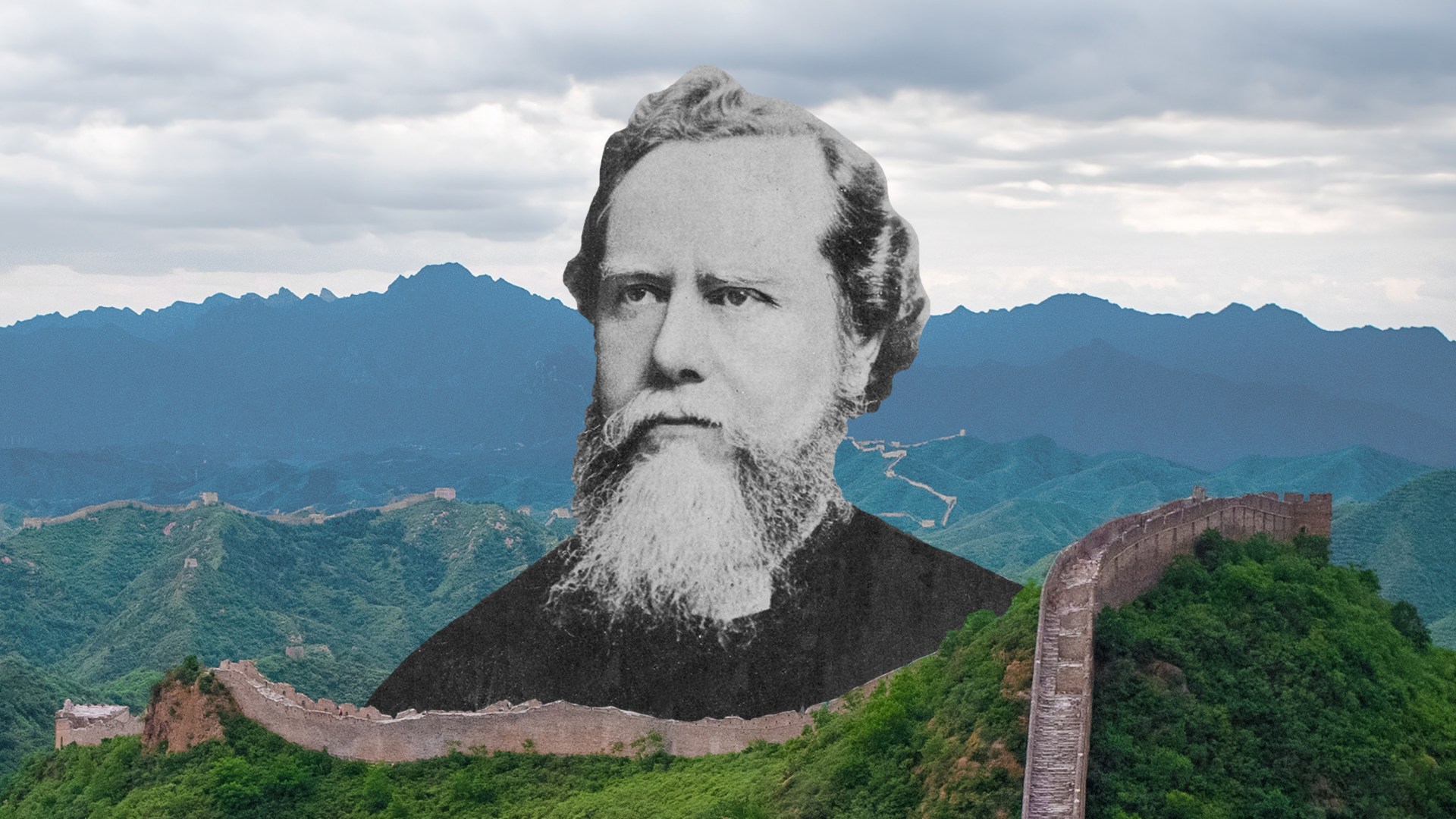

This simple but overwhelming command is the spiritual core of the mission that OMF continues, the work of British missionary James Hudson Taylor (Dai Desheng 戴德生, 1832–1905), who founded OMF—then known as China Inland Mission (CIM)—in 1865. Taylor’s pioneering work in China’s inland was groundbreaking, and he is remembered for his missional drive, spiritual discipline, evangelistic strategy, contextualization to Chinese culture, and support for single women missionaries.

For Chinese Christians in China, Taiwan, and overseas, Taylor remains a peerless figure. He is loved and admired, and many Chinese Christians can still recite his best-known words: “If I had a thousand pounds, China should have it. If I had a thousand lives, China should have them. No! Not China, but Christ.”

Taylor’s descendants of four generations, each boasting at least one missionary dedicated to the Chinese church, are affectionately called an example of Dai Dai xiang chuan (戴戴相传), a “legacy of dedication from one generation to the next.” Indeed, the very existence of tens of millions of Chinese Christians and thousands of Chinese churches all over the world today is significantly the legacy of Taylor and CIM/OMF.

“History has proved that the fruit of the gospel produced by CIM has a strong foundation and can stand up to the winds and rains,” wrote mainland Chinese pastor Yan Yile. “Even though Western missionaries were forced to withdraw from mainland China in 1950, the seeds of the gospel had been sown among the people, and, for the first time, Christianity really took root in Chinese soil.”

As the Chinese church faces new challenges, it’s time to revisit those roots. In mainland China, Christians are experiencing real persecution and suppression, and many missionaries from overseas have been driven out of the country. The church in Taiwan is dealing with rising secularization, a shockingly low birth rate, constant threat of war, and disinterest in faith among younger generations. In the Chinese diaspora, churches are inevitably affected by deteriorating relations between China and the West.

In these troubles, some Chinese Christians are thinking back to the suffering and setbacks Taylor and CIM experienced more than a century ago during the Boxer Rebellion, and to the 1950s, when Western missionaries were forced to take a “reluctant exodus” from China. The persistence of those generations—and of Taylor in particular—can inspire and edify us still.

Scaffolding the church

Patrick Fung was the first Asian general director of OMF. On November 27, 2023, Fung handed over the leadership role to Joseph Chang, the 11th general director in the organization’s nearly 160-year history. When interviewed by CT about Hudson Taylor’s legacy, Fung said he believes Taylor's greatest contribution to the Chinese church in China was his concept of “scaffolding” as a metaphor for transitioning away from foreign oversight to local church leadership. As Taylor explained it, Western missionaries in China were like a scaffold: necessary for initial construction, but never meant to be permanent.

Once the local church was established, Taylor taught, foreign missionaries should train up local Christian leaders. And once the local leaders were trained, the scaffold could be dismantled. “Hudson Taylor never wanted to build up CIM like building his own kingdom,” Fung told CT. “His vision went beyond himself. It’s God’s people serving God for the Chinese, and for the Chinese Christians to rise to the challenge and lead the Chinese church.”

This is the meaning of Taylor’s famous interjection, “No! Not China, but Christ.” His goal was to exalt the name of Christ and abide in him, Fung said, including amid great hardship: “Even when he suffered from depression, Hudson Taylor relied on ‘abiding in Christ’ to experience the grace of God.”

Just three years after CIM was founded, its headquarters was set on fire in the Yangzhou riot. CIM missionaries, including Taylor’s wife, Maria, who was pregnant at the time, were nearly killed. After the riot, Taylor fell into severe depression, and it was only in Christ, Fung said, that Taylor could continue. “His whole theology of trusting in God was not learned in a classroom setting,” Fung mused, “but in suffering and difficulties.”

It’s a theology worthy of emulation for Christians today, says I’Ching Thomas, author of Jesus: The Path to Human Flourishing: The Gospel for the Cultural Chinese. “In the face of persecution, Hudson Taylor’s unwavering love for Jesus was what gave him the faith, strength, and hope to persevere through even the most painful experiences,” Thomas told CT. Like Taylor, we need a “clear focus on what and where God calls us, and a profound understanding and embrace of the theology of suffering. It is my observation that many Christians today are still grappling with this.”

Beyond suffering

To Joy Li (pseudonym for security purposes), a young Christian who returned to China after going abroad for graduate school, emphasizing suffering alone is not the best way to encourage younger generations to follow Taylor’s example.

When Chinese Christians talk about Taylor’s legacy, Li said, they lionize his sacrifice, perhaps to pressure young Christians into mission work. But Chinese Christians shouldn’t overstate the persecution they face, she contends.

“Compared to the persecution Christians experience in some other parts of the world, such as some Muslim countries, the persecution we suffer is minor,” she told CT. “And compared to the ‘slowly boiling frogs’ situation in the West—where faith is declining in an environment of freedom and comfort—it can even be said that we Christians in China have a good opportunity given by God to keep our faith on fire.”

Overemphasizing suffering and sacrifice may only “frighten the young people of today and make them more afraid to step out of their comfort zone into the mission field,” Li said.

Better to build on his legacy by learning from his “wisdom and courage, as shown in his medical mission, in CIM’s respect for the Chinese culture—like Western missionaries wearing Chinese clothes—and in the acceptance of single female missionaries,” she said. These were all “strategic and innovative approaches to mission” in Taylor’s day.

Innovating anew

What does innovation look like in Chinese mission now? “In today’s world, the challenges to mission are more complicated” than the violence of Taylor’s day, Fung observed. “Hostility against Christian faith is one. Global migration is another. Today’s mission is no longer one direction—from the West to the rest of the world—but more crisscrossing.”

And missionaries themselves are different too, he added: “We also need to acknowledge that the new generation of Christians comes from a background probably much more broken than the generation 100 years ago (e.g., just look at the divorce rate). We need to deal with our own brokenness first, if we believe God is bringing healing to this broken world.”

One consistent project, though, is contextualizing the gospel to make sense in different cultures and different eras. CIM missionaries’ willingness to wear Chinese clothing as well as braids in the style of the Qing dynasty era—for which they were mocked by some Christians in the West as “pigtail missionaries”—minimized cultural hindrances to spreading the gospel, Fung believes.

Taylor’s contextualization went well beyond appearances, however. He required missionaries to learn the Chinese language and gain a deeper understanding of traditional Chinese culture by reading works by ancient Chinese philosophers, Fung said. “They had to study the Analects of Confucius and the writings of Mencius. There were six levels of exams they had to pass, and in level 5, they had to write down all the names in the Bai Jia Xing (The Hundred Family Surnames) from memory, which very few Chinese people would even be able to do today. That’s how serious Hudson Taylor was about cross-cultural missions. It was no joke when he said we need to live out an incarnational ministry.”

That commitment never meant subverting gospel truth for cultural appeal. Taylor’s “contextualization was about culture, not theology,” explained Andy Johnson, associate pastor of Capitol Hill Baptist Church in Washington, DC.

“Behind his ponytail and Chinese robe, through his Chinese speech and cultural allusions, he preached the same, often-offensive, biblical message that all other faithful missionaries preached,” Johnson wrote. “His contextualization was for the sake of clarity, not for his listener’s comfort, and the offense he wanted to avoid was needless cultural offense, while proudly embracing the offense of the cross.”

Across the Strait

Taylor’s unwavering embrace of the cross had a profound impact in Taiwan as much as mainland China. “The influence of the four generations of the Dai (Taylor) family on the church in Taiwan is not only in the past tense but in the present,” said Ray Peng, a young missionary leader in Taiwan and founder of the mission mobilization organization WE Initiative.

Speaking of the contributions that generations of the Taylor family have made to Taiwan, Peng counts the blessings as if they were treasures of his own family, rattling off the achievements of James Hudson Taylor II (Dai Yongmian 戴永冕, the third generation), James Hudson Taylor III (Dai Shaozeng 戴绍曾), and James Hudson Taylor IV (Dai Jizong 戴继宗) who serves as president of China Evangelical Seminary (CES) in Taipei today.

Beyond the immediate Taylor family, Peng told CT, many OMF missionaries have been God’s hands and feet in Taiwan. He pointed to Ross Paterson (巴柝声), a British missionary who has profoundly influenced the charismatic movement in Taiwan over the past 30 years. Dutch missionary Tera van Twillert (林迪真) has led the Pearl Family Garden Woman’s Center, which ministers to disadvantaged women in the red-light district of Wanhua, for more than 20 years. New Zealand missionary Judith Jackson (张丽安) worked with students in Campus Evangelical Fellowship. In these and other OMF missionaries, Taiwan has been blessed with a “great cloud of witnesses” (Heb. 12:1).

The advantage of Taylor’s grassroots mission, says Yan Yile, the mainland Chinese pastor who wrote about CIM history, was its lack of “intellectual pride and ideological baggage.” Where other missionaries focused on Chinese elites, Taylor’s team “could establish local grassroots churches, which were easy to take root and were stable, and had a high survival rate regardless of the changes in the external environment.”

OMF missionaries in Taiwan have preserved that missiological philosophy of ministering to the disadvantaged, Peng said. They still give special attention to frontline service industry workers, migrant laborers, farmers, fishermen, and single-parent families in remote areas.

But the contributions of OMF missionaries to theological education in Taiwan are noteworthy too. On the Taipei campus of CES, Dai Jizong (Hudson Taylor IV) pointed to an enlarged vintage photo on his coffee table depicting founders and leaders of influential evangelical organizations and churches in Taiwan, all of whom had deep relationships with OMF.

Dai himself remains a coworker with OMF to this day. As a child of missionaries (the fifth generation of Dai) who was raised to be fluent in Mandarin, attending local schools in Taiwan, he was often asked if he too would enter missions when he grew up. (His Chinese name, Jizong, means “inherit the legacy of my ancestors.”) He was so annoyed by questions like this as a kid, Dai told CT, that he had decided he’d avoid missions altogether—but, at 24, he changed his mind, submitted to God’s calling, and entered seminary.

His family heritage “used to be a burden, but now it is a blessing,” Dai marveled, telling CT he has experienced God’s “miraculous” provision many times in his own ministry, just as his great-great-grandfather did. Taylor’s “unwavering, daring faith in the promises of God was instrumental to him” and continue to be instrumental in Dai’s own life.

A new generation

The success of Hudson Taylor’s scaffolding and contextualization strategies is easily seen in the lives of Chris and Emily Cheng, second-generation Christians from a Chinese church in Boston who are now serving as missionaries in Japan. Though delayed by the pandemic—and forced to spend several months couch surfing with their two young children before they could depart—they started their ministry with OMF at the organization’s language school in Sapporo, Japan.

God “put in my heart a yearning to serve among unreached people groups, but I found myself questioning whether I could support my family financially and my children educationally if I were to pursue a career in full-time missions,” Chris Cheng told CT.

“Into this, God challenged me and exposed how little faith I had in him as I tried so hard to maintain control over my own life,” he continued. “As I began to explore missions more seriously, the words of Hudson Taylor rang true to me: ‘God’s work done in God’s way will never lack God’s supply.’ The legacy of Hudson Taylor is to live by faith such that when there is need, we pray and look to God for provision.”

The Chengs’ inspiration to ministry is no surprise to Patrick Fung. “Hudson Taylor embodies the far-reaching vision of Psalm 145:4 (‘one generation commends your works to another’) for sharing Christ with the world through equipping the next generation,” he said. Taylor mobilized younger Christians to mission work in his own lifetime, and he continues to mobilize more today.

“Hudson Taylor was not a superhero,” Fung said. “He was frail and, as historian Kenneth Latourette said, not particularly intelligent. He needed help from others, and most of all, from God.”

“Yet he had one thing in mind, one thing only: that the gospel should reach inland China,” Fung continued. “His whole life was about this one thing only. His commitment of trust and prayer that moved him on and allowed him to be used by God shows us an example of what we can also do. His story will inspire a new generation to make that kind of commitment.”

Isabel Ong, CT associate Asia editor, also contributed to this article by carrying out interviews with Patrick Fung and James Hudson Taylor IV.

Sean Cheng is CT Asia editor.