Laura was volunteering at the welcome desk of LIFE Central church in Auckland in April 2015 when a friendly man introduced himself, asked a few questions about her church, and then left.

Unbeknownst to Laura, after this brief encounter, the man organized one of his coworkers to return to the church the next week. The woman explained that she had just moved from South Africa as a student conducting research on education. After talking for a bit, Laura started to open up to her about some of her struggles and questions about the faith. In response, the woman suggested Laura meet with her mentor, who she said could address Laura’s problems about the Bible.

She began meeting with the woman’s mentor, a Korean woman also visiting from South Africa, for weekly Bible studies. After a few weeks, the mentor began pestering Laura to join a larger six-person class that met three times a week. Laura eventually agreed.

As someone who had experienced hypocrisy and lukewarm community at the mainline Presbyterian and Pentecostal churches she attended in the past, Laura found the intense, Bible-based classes compelling. Laura recalled a tight-knit group of South Africans, Koreans, and New Zealanders eager to learn God’s Word. Laura said the instructor taught her how to read Jesus’ parables and the Book of Revelation as prophecies foretelling Jesus’ Second Coming. The teacher stressed that she and her fellow students needed to know the secret meaning of certain Bible verses to obtain true salvation.

“At the time, I thought it was a beautiful way to read the Bible—it was so poetic,” Laura said. By the end of the year, she and her five classmates officially joined (or “passed over”) into a group she then learned was called Shincheonji. (Laura asked to use only her first name as she still has friends in the group.)

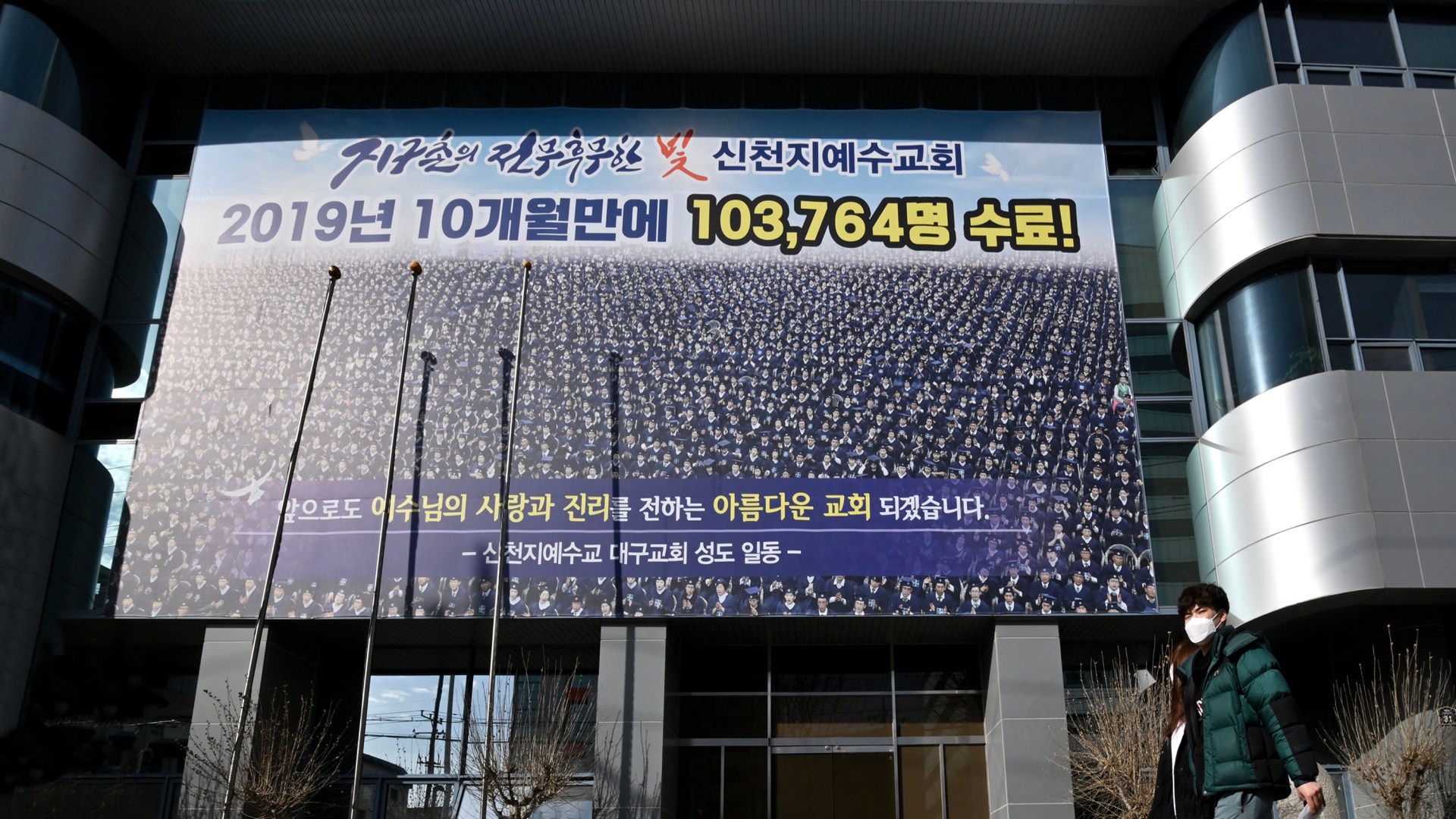

Shincheonji, which means “new heaven and new earth,” is a religious movement established in South Korea in 1984 by Lee Man-Hee. Members are taught that Lee is the “promised pastor” of the New Testament—the messenger mentioned in Revelation 22:16—and that the Book of Revelation is written in parables that only he can understand. The group is known for its intensive Bible studies, recruitment of members from existing churches and Christian fellowships, and use of deceptive practices like withholding names and affiliation.

After spreading in South Korea, Shincheonji expanded internationally in 1990. The group’s internal statistics from 2019 obtained by CT said that almost 32,000 of the group’s about 240,000 official members live outside of Korea.

In response, Christians around the world have pushed back. In South Korea, churches routinely put up signs that read “Shincheonji is not welcomed here.” Former members have shared their stories on websites, podcasts, and internet forums like Reddit to debunk Shincheonji’s theology and expose its deceptive practices. In New Zealand, pastors have held talks and seminars to inform church leaders on how to protect their flock. Christian counselors provide counseling for people leaving Shincheonji.

CT tracked Shincheonji’s spread in New Zealand over the past eight years, interviewing former members, pastors, and experts on what churches around the world should look for and how churches can respond to the group. Shincheonji in New Zealand did not respond to CT’s request to comment by publication time.

From humble beginnings

Born in 1931, Lee Man-Hee is a Korean War veteran and farmer who claimed that he experienced “visions and revelations from divine messengers and from Jesus himself,” according to a 2020 article by sociologist Massimo Introvigne, who interviewed Lee and other Shincheonji members. (Introvigne, founder of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), has been criticized for being sympathetic to groups like Scientology.) In the ’60s, Lee joined a fast-growing religious group called the Olive Tree, whose founder, Park Tae Son, claimed to have the power of healing and to be the last prophet before the millennial kingdom. Eventually Park started teaching that he was the Messiah and the Bible was wrong. This led Lee and many others to leave the group.

WikiMedia Commons

WikiMedia CommonsLee was then a member of Tabernacle Temple, a group founded by eight people who gathered on Cheonggye Mountain for 100 days and believed the Holy Spirit gave them an inspired interpretation of the Bible. Yet the group fell into corruption and division, with its founder arrested for fraud. Lee was outspoken about the corruption of the Temple and eventually started his own religious group called Shincheonji in 1984.

“It wasn’t successful at first,” explained Ezra Kim, a California pastor with an active ministry counseling current and former Shincheonji members. The group, which primarily focused on Lee Man-Hee’s interpretations of the Book of Revelation, had less than 120 members in 1986, according to Introvigne. Growth began to pick up after the formation of an in-house “seminary” called Zion Christian Mission Center in Seoul in 1990, which prepared members through courses and exams. By 2007, Shincheonji had 45,000 members.

To grow their numbers further, Shincheonji members began targeting Christians from existing churches to join their Bible studies, Kim said. From 2010, the group began employing deceptive tactics (described by members as practicing “wisdom”) that grew its numbers exponentially. By 2016, Shincheonji reported having 170,000 members.

Shincheonji’s first overseas branch opened in Los Angeles in 1996, with subsequent branches in Berlin (2000), Sydney (2009), Cape Town (2012), and elsewhere. By 2019, Shincheonji mission centers had been established in 29 countries.

Shincheonji reaches New Zealand

Shincheonji’s first “missionaries” arrived in New Zealand on visitors’ visas from South Africa in March 2015, a month before making contact with Laura and her classmates. After Laura officially joined the group, leaders in South Korea appointed her and two other members as key leaders and legal trustees for Shincheonji’s official presence in New Zealand, under the name Rakau o te Ora (meaning “The Tree of Life”).

“[When] they asked us to sign and become trustees, we were like ‘peak passion,’” Laura recalled. “It was like the beginning of a relationship, [when] you’re only seeing the good things.”

By the time news of Shincheonji had reached New Zealand media in 2017, the group’s ranks had increased to around 70 members and recruits, most of whom were poor college students, according to Laura. Most of Shincheonji’s growth in Auckland came from Shincheonji members visiting church congregations and campus ministry groups and inviting Christians to join Bible studies, she said. When asked, they would say they were part of Zion Mission Center, New Heaven New Earth, or Mount Zion. (In recent years they have also used names like Cornerstone and Pathways Ministries.) They also falsely claimed their instructors were theologically trained at New Zealand’s Bible colleges, according to Laura.

Members often recruit unsuspecting friends and acquaintances. For instance, in 2017, Jeremy Chong (no relation to the author) had recently graduated from the University of Auckland when his friend and fellow campus ministry volunteer persuaded him to attend a new class led by his mentor. When he showed up at the address for the class, he was surprised to find a lecture room set up inside a suburban home.

In his class of 10 students, Chong later discovered that half of them (including his friend) were already Shincheonji members pretending to be first-time learners. Initially the lessons took place once a week but eventually grew to twice and then three times a week. Gradually, the teachers began to say, “We’re part of something more, but we’ll reveal the truth when you’re ready,” Chong wrote in an online testimony. They also instructed Chong and his classmates to cut ties with their churches, calling them “false seeds” who were not from “the true river.”

Eventually, Chong’s instructors announced a special session where he and his classmates had to dress up nicely in a white shirt and a suit. What he thought was another class turned out to be a big worship service at a rented office building in central Auckland that Shincheonji used as its temple. There, he and his other students “passed over” into the group.

“There were a lot of people cheering,” Chong recalled. “We bowed down to a screen of Lee Man-Hee. In my head, I thought: ‘Why am I doing this?’ But it happened. And after this, they then told us, ‘Now you know that we’re part of this group called Shincheonji.’”

Lying and deception in Shincheonji

Shincheonji teaches its students not to let their friends and family know about their classes until they have become sufficiently conditioned to accept their more controversial teachings. For instance, Josh was the student president of Auckland Student Life (a campus group affiliated with Cru) in his senior year when he was first asked to lie to his family about attending a thrice-weekly “Bible study” with a man who claimed his name was Matt. Josh had first met Matt in October 2018 through a high school friend. When Josh shared that he was going on a summer mission trip, Matt then invited him to some “mentoring sessions” he was leading. (Later, Josh found out that Matt was using a fake name).

Josh recalled that his new mentor said a couple of “outrageous things,” such as God doesn’t answer prayer. “But to me, it seemed like they were all from the Bible, because he was just able to say Scriptures off the top of his head.” (Josh asked to only use his first name, as he continues to counsel current and former Shincheonji members.)

Shincheonji instructors eventually convinced their recruits that God permits lying if it is done for “God’s will.” Before Josh’s sessions commenced in January 2019, his mentor warned him to keep them a secret, pointing to Abraham’s silence before heading out to sacrifice Isaac in Genesis 22. Josh concocted a story about teaching private guitar lessons three mornings a week, a lie he told his parents, his girlfriend, and Student Life colleagues.

When church leaders and a campus staff worker confronted Josh with evidence that he was attending Shincheonji classes, his Shincheonji instructors gave him step-by-step instructions on how to deny his involvement. They even gave Josh pre-written letters expressing “inexplicable hurt and confusion” about his family and friends’ accusations and claiming that he was no longer involved in Shincheonji activities. Josh sent the letter to the church yet continued his classes, and in May 2019 he “passed over” into the group.

Inside Shincheonji

Life inside Shincheonji in New Zealand was relentless for the former members who spoke to CT. Chong said that after “passing over,” Shincheonji became church for him. Lessons were scheduled for every day of the week, and he was scolded for working and urged to abandon his family to “evangelize.”

Leaders asked Chong to give them the names of all his friends, including private information such as “physical descriptions, their relationships, what their weaknesses are, how well they knew their Bibles … so we would know what to target,” he wrote.

Alannah (then a close friend who is now married to Chong), recalled how tired he was all the time. “There were a couple of times we’d be hanging out together … and he would say: ‘I’ve got to go out and meet someone.’” She wondered if he was seeing his ex.

For Josh, the lying continued. “I was fully dependent upon them for my decisions … [the question] ‘What do I say?’ was always filtered through them.”

Zealous to give his life to spread these teachings, Josh worked his way up the ranks to become a cell leader and began to recruit others into Shincheonji using the same methods he was recruited with. Josh and other members were given “unrealistic goals to achieve” and challenged to change their mindsets since the “second coming of Jesus” had come with Lee Man-Hee. To justify studying until 4 a.m. for tests, “I was told that I should not be able to sleep if I perceived how important this work was,” Josh wrote.

Shincheonji’s slowing spread in New Zealand

By July 2022, there were at least 200 Auckland-based members from a broad range of ethnic groups, according to internal lists obtained by CT. In contrast, numbers in the capital city of Wellington had grown more slowly: Between the time Laura and several other members started a branch there in 2018 and 2022, Wellington had only grown to 35 members. Laura remarked that Auckland’s large immigrant and ethnic church populations have proved more fertile soil as “Asian culture takes more easily to the ‘heavenly culture,’” which is what Shincheonji calls traditional Korean culture.

Pacific Island culture is also very hierarchical, Laura said, so in 2023, New Zealand–based Shincheonji members began sending locally trained missionaries to Samoa.

In contrast, the more Pakeha (New Zealanders of European descent) population in Wellington proved to be more independent, individualistic, and skeptical, Laura said. “It’s a lot harder for them to accept the Korean culture and collectivist ideas of [Shincheonji].”

Another factor for the slow growth in Wellington could be an increased awareness of Shincheonji and its tactics.

Since 2021, New Zealand–based members of the Shincheonji forum on Reddit have frequently posted “sightings” and warned about the group’s deceptive recruitment strategies, such as impersonating a local Bible college and using various front groups like Heavenly Culture, World Peace, Restoration of Light (HWPL). Local media have reported on ex-members’ stories, and evangelical church leaders in Wellington have also been proactive in warning their congregations, other local churches, and the general public about Shincheonji.

In 2019, Andrew Southerton, senior pastor at City on a Hill in Wellington, wrote on his church website that while Shincheonji’s classes appear like Bible studies, they are in reality “an exercise in social engineering.”

He added that “the cult has sought to exploit many of the best aspects of City on a Hill for its own ends—our open and welcoming culture, our love for sharing the gospel with others, and our deep desire to be learning and growing from God’s Word.”

Churches throughout New Zealand report that Shincheonji had swept up entire families, including key leaders, into the group. Often, the extent of deception and damage is only discovered after months of covert activity. Steve Worsley, lead pastor at Mt Albert Baptist in Auckland, said Shincheonji targeted his church extensively between 2016 and 2018.

“When asked what attracted members to Shincheonji, I was stunned by the answer: ‘Biblical truth,’” Worsley wrote on his denomination’s website. “If people are experiencing greater hunger for Bible knowledge in cults than in regular New Zealand churches, what should churches do about that?”

Chong’s experience mirrored Worsley’s sentiment. He felt “super religious” during his time in Shincheonji. “After all, I was going to a religious thing five times a day, learning the Bible,” Chong wrote. “It makes you feel hyper-religious. When I did everything, I felt very connected to God. But ultimately, it was a completely works-based group.”

The turning point for Chong was when his teachers couldn’t give a proper answer to why they denied the divinity of Christ. Chong left Shincheonji in 2018 with the help of a Christian friend.

Help getting out of Shincheonji

What can family members do when they find a loved one is involved with Shincheonji? Kim, the pastor in California who leads Bible studies for ex-members of Shincheonji, suggests three steps to take.

First, do nothing, he said. People usually want to say, “Shincheonji’s a cult” or “Your Bible study is wrong,” Kim noted. Yet Shincheonji instructors have already conditioned them to believe these claims are a form of persecution.

The next step is to foster a stronger relationship with the person without speaking negatively about the group. Members of Shincheonji and other cults typically spend more than 20 hours a week together and experience a heightened sense of community and deep purpose. In contrast, Kim points out that most families struggle to have meaningful relationships and rarely talk about issues together.

“How can you do deep conversation suddenly when you’ve never done this kind of conversation in real life?” Kim said. “To save your loved one [from Shincheonji], you need to restore your relationship with them first.”

Only within the safety of a trusted relationship—a process that often takes months or years—is the final step of gently restoring them (Gal. 6:1) possible. Options include introducing Shincheonji members to former members or experienced pastors, sharing the stories of former members, or passing along resources explaining Shincheonji’s frequent doctrine changes, Lee’s past involvement in doomsday sects, and ultimately the better and completed ministry of Jesus Christ (Heb. 1:2).

For Josh, it was through discovering these resources and seeing the numerous contradictions within Shincheonji’s teachings that he was eventually convinced to leave the group in 2022. “What had once started as such a logical word [referring to Shincheonji’s teachings], was now so illogical,” he said.

Christian leaders should also be aware of cultural practices in their own ministries that commit the same sins as Shincheonji. “If cults keep their real agendas from new recruits, then are we fully transparent when we promote or invite people to attend church programs that have evangelistic content?” Worsley observed. “If cult leaders may not be questioned, do we pastors allow our leadership and Bible teaching to be open to question?”

For instance, a recent investigation into Arise Church, New Zealand’s largest megachurch, revealed an internal culture with several features similar to Shincheonji such as centralized power and the practice of “uplining,” or passing private information on to superiors without consent.

Tore Klevjer, an Australia-based biblical counselor who frequently ministers to former members of Shincheonji, suggested viewing Shincheonji through the lens of an abusive relationship. Former members who struggle to engage with the Christian faith will “need love and care and space to heal at their own pace,” Klevjer said.

For those who choose to keep reading their Bible, he recommends changing to a translation different from what was used in Shincheonji (typically the 1984 New International Version) to read God’s Word with “new eyes and not automatically see the cult interpretation.” When reading the Bible is too difficult, Tore counsels ex-members to pursue other spiritual disciplines or to reflect on God’s creation and his attributes of love and mercy.

Josh points out that most people will eventually leave Shincheonji but need help rebuilding their lives, and that it will take time for them to reconsider Christianity. The eventual death of Lee, who is now 92 years old, could also prompt doubts. (According to Introvigne and former leaders, prophecies taught in Shincheonji claim that Lee will not die.)

“Try and be there for them when the time comes,” Josh said. He regularly prays for his fellow ex-members as well as members who are unable to leave Shincheonji or those who have considered leaving. As for his former mentor, “He’s just a brick wall,” Josh said. “I hope he leaves and can realize all the wrong things he’s done. I just see him as a victim—conditioned, exploited. I do feel sorry for him.”

Laura’s decision to leave Shincheonji was sparked by a phone call from a former senior Shincheonji member she admired, who told her that she had left the group. “It gave me permission to think about my own doubts,” she said in an interview with Radio New Zealand. She cut ties with the group in 2020. However, it took another year before Shincheonji finally removed her name as one of its New Zealand trustees and guarantors for its building’s lease payments. Today, she no longer identifies as a Christian.

Laura was circumspect when asked what followers of Jesus could have done differently for her. Like Kim, she noted that if Christians had tried to use doctrine to convince her that Shincheonji was wrong, she would have been prepared with answers for their questions. She would have assumed that she was being persecuted.

“So the best thing you can do is to show love,” Laura said. “That’s what Christianity is about, right?”

Additional reporting by Angela Lu Fulton.