At 17, I had no career aspirations, other than attending college. My senior year I enlisted in the army, planning to use the GI Bill to pay for my education. A close friend, also a first-generation student (a term I would later learn), was doing the same, so I simply followed her lead.

A few weeks before high school graduation, a math teacher and school counselor offered some much-needed advice, showing me other ways to pay for school. I was able to unenlist from the army, and I started at a community college. I paid for tuition and fees with aid from six sources: (1) the Board of Governor’s Fee Waiver for enrollment (now called the California College Promise Grant), (2) a federal Pell Grant, (3) Cal Grant B, (4) the Education Opportunity Program’s book, (5) public transportation vouchers, and (6) work study. I had no idea what any of these meant at the time, but advisers and professors graciously mentored me along the way.

In two years, I completed an honors curriculum and the transfer requirements to attend UCLA. Its financial aid package prompted my decision to enroll, despite being accepted at my top choice, UC–Berkeley. Not having a clear financial plan for transportation to and from northern California, I felt overwhelmed since I was financially supporting myself.

Being a first-generation Latina, I first realized I was poor when I transferred to UCLA. It wasn’t the myriad financial aid grants and jobs I needed while living in East Los Angeles; it was the Gucci bags and other luxury items my peers carried. Still, I was thirsty for knowledge and focused on my newfound goal: helping others persevere through college. Some of my desire was rooted in selfishness—it was lonely to be one of a handful of Latino students in the lecture halls. But I also wanted to give back to my community.

Through my undergraduate journey, I discovered that I loved learning. I also learned that I wanted others like me to have an easier time getting through college. Various academic advisers encouraged me to continue my studies, and I began a master’s program three years later. While working toward my degrees, I had opportunities to return to my high school to serve in various roles, including enrollment officer, tutor, college adviser, and graduate career intern. I later worked for the Early Academic and California Student Opportunity and Access Programs. Through these programs, I helped students become college ready.

Leveraging Social Capital

Most recently, in 2016 I completed my doctoral studies in educational policy and social context at UC–Irvine. My research explored how to provide higher education opportunities and resources for low-income, first-generation students. The odds are stacked against underrepresented populations striving for academic success. Because I lived this experience, I know, beyond statistics, the struggle to make college enrollment and graduation a reality.

I was especially interested in how ability in mathematics affected the trajectories of my community. Conventional research has shown that mathematics predicts college enrollment. In my research, however, I found that despite low math skills, a significant portion of Hispanics enroll in college. According to my research, relationships with teachers were pivotal in encouraging students in our community to enroll in college.

College opportunities and social mobility decrease for minority students, according to the US Department of Education’s 2016 “Advancing Diversity and Inclusion in Higher Education” report. It is more difficult for minority students to apply, be admitted, enroll, persist through college, and graduate. And that’s if they make it to college. We are living in socioeconomically siloed communities, where, as The Atlantic’s Ronald Brownstein wrote in “The Challenge of Educational Inequality,” “the racial disparities in educational outcomes remain imposing.” This leaves Latino youth in desperate need of mentors with social capital. My story is typical of many first-generation students from working-class backgrounds. Without parents who understand higher education, or who have the resources to provide emotional or economic support, students are left to figure it out on their own unless a mentor or older adult can offer support, as was my case.

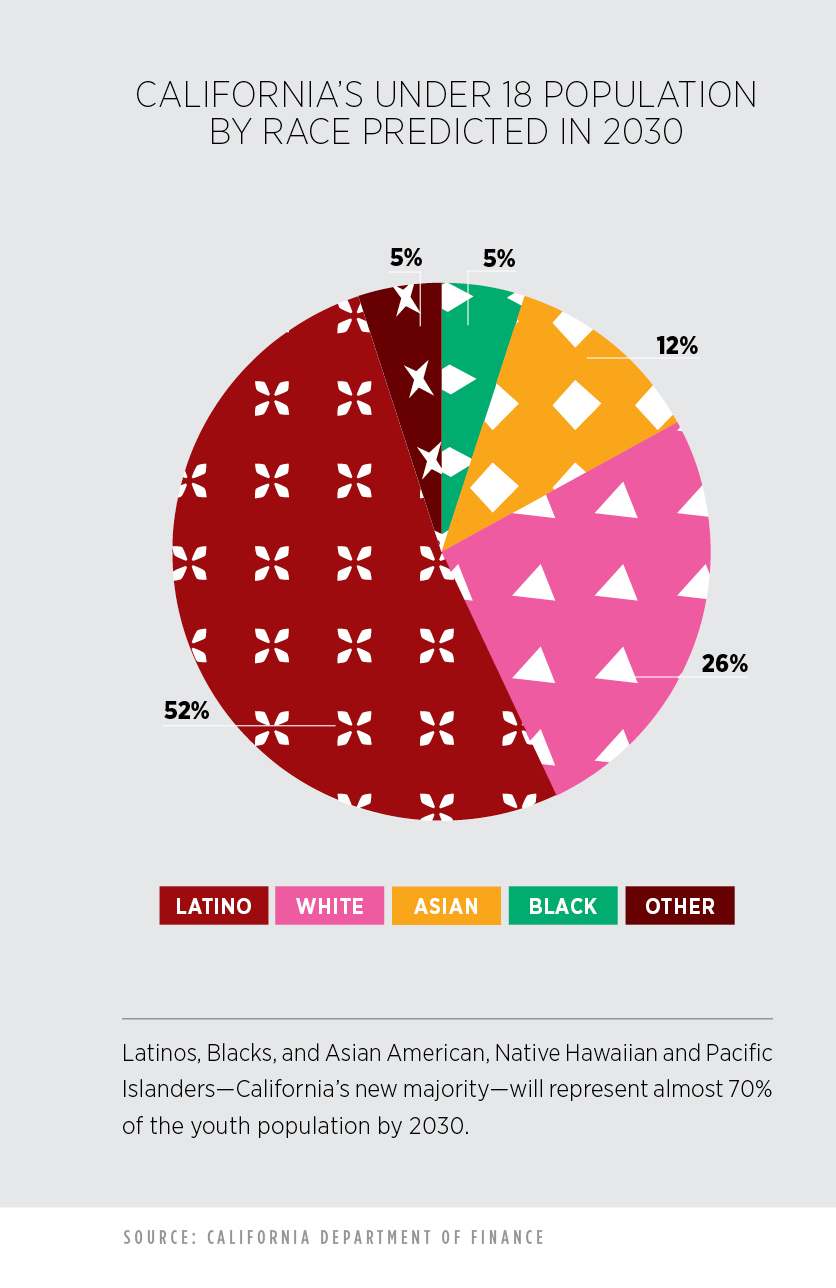

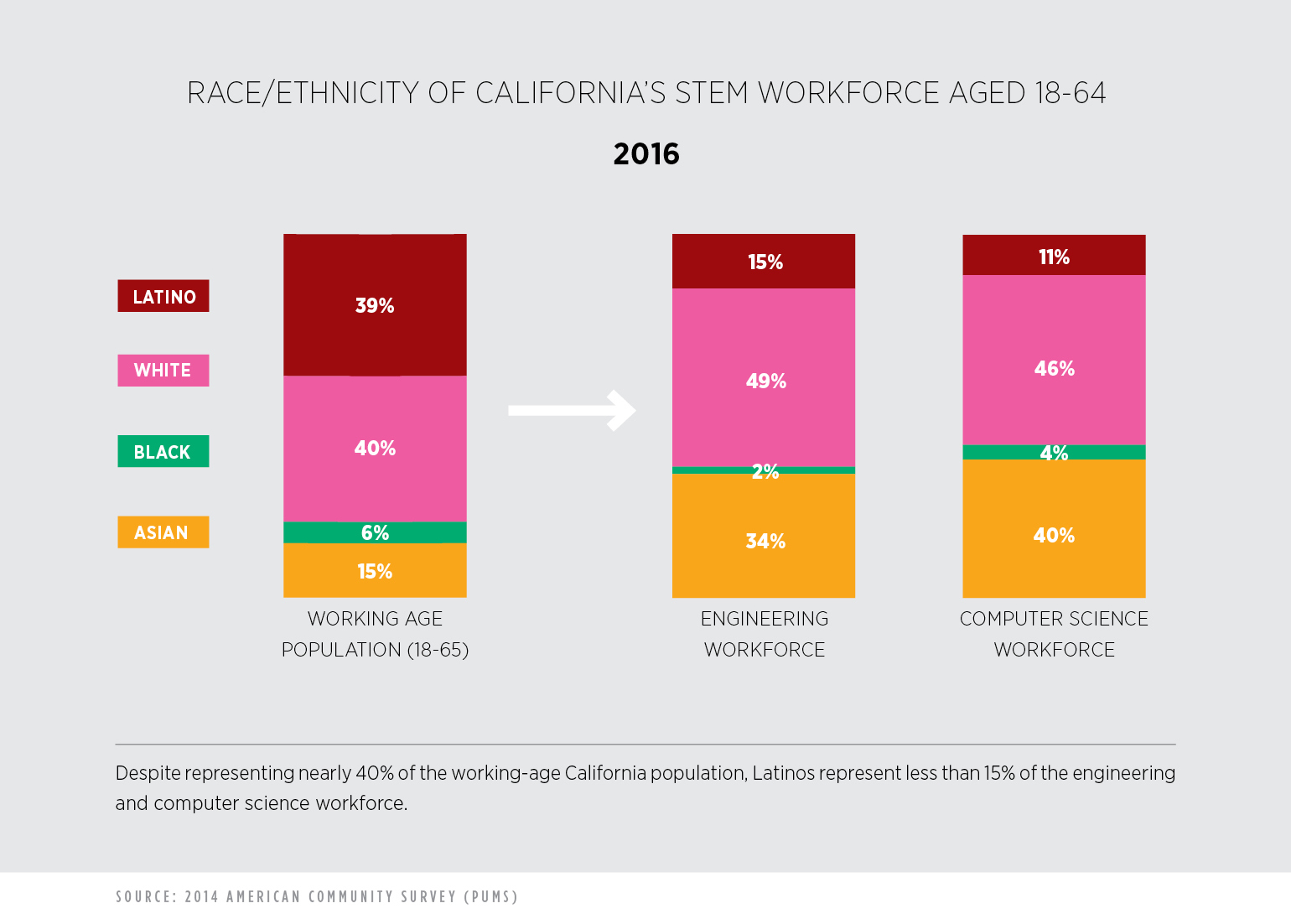

According to the Public Policy Institute of California, we are likely to face a shortage of workers with postsecondary education by 2025. For example, the fastest-growing job sectors in California are projected to be science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) and health-related fields. But, according to a 2016 College Campaign report, there are not enough projected graduates to meet the demand. With guidance, opportunities, and specified funding, underprivileged, first-generation students could easily fill the gap in these fields.

Finding Ways to Support

After almost 20 years of working in this area, I have learned that students are not defined by statistics. I now work as the student success manager for an innovative nonprofit. We provide financial support beyond the grants that students already qualify for. We also offer mentors who help them navigate college. After students complete their first year, they are matched with a career coach. The process isn’t always seamless; many students have to pause their studies or change direction due to financial strain, family conflicts, or other stresses. But the more supporters in the students’ corner, the better their prospects.

My professional goals were not always clear to me. I was blinded by having to hustle in college. My mother and father completed only an elementary education in Mexico but always aspired for more. Despite their low academic attainment, they worked hard to provide and inspired my education. They were not, however, equipped to walk with me through my college journey. As a result, I depended on others for support. I have grown to understand the benefit of a college education, and my experiences have shaped my life calling into a career that fosters equity and access in higher education and beyond.

Alma L. Zaragoza-Petty, PhD, is a Los Angeles native and firstborn of immigrant parents. She currently works in the Los Angeles area as a first generation student retention specialist in higher education. She is co-host of The Red Couch Podcast, a brown-eyed social and political commentary with a hood twist. She is an expert in educational policy and social context. As she prefers the term Latinx, the editorial decision to use Latino and Hispanic in this piece was made by Christianity Today.