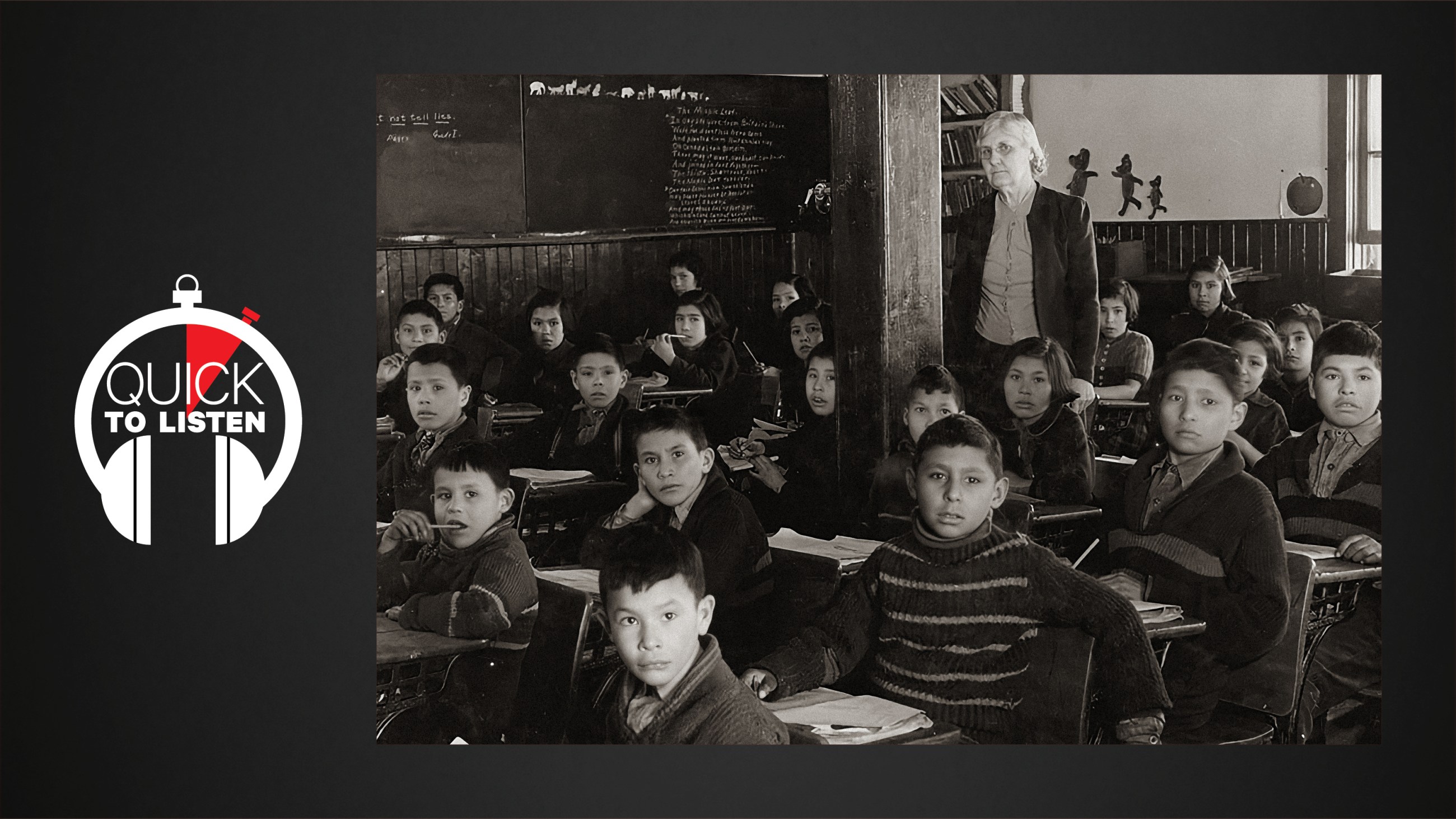

Half a dozen Canadian churches have been set on fire or burned down this summer. This arson has come at a time when multiple unmarked graves have been found across the nation on the grounds of now-defunct residential schools. Operated by multiple churches, including the Roman Catholics, Anglicans, Presbyterians, and United, the Canadian schools were part of a 20th-century government program to assimilate its First Nation community.

The government forced students to attend, separating them from their families at a young age. Once there, they were forbidden from speaking their native language and punished severely if they ran away. Many died at the school from disease and suffered from hunger and physical abuse.

The trauma brought on by these schools has carried on for generations. Much of it was shared during a Truth and Reconciliation Commission where survivors told stories of their time.

Jimmy Thunder teaches indigenous ministry at Horizon College and Seminary in Saskatoon and is the founder of Reconciliation Thunder, a nonprofit focused on helping leaders respond to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s 94 Calls to Action.

Thunder joined global media manager Morgan Lee and executive editor Ted Olsen to discuss the Christian history of Canadian residential schools and learn how many First Nation people regard Christianity today.

What is Quick to Listen? Read more

Rate Quick to Listen on Apple Podcasts

Follow the podcast on Twitter

Follow our hosts on Twitter: Morgan Lee and Ted Olsen

Learn more about Reconciliation Thunder

Music by Sweeps

Quick to Listen is produced by Morgan Lee and Matt Linder

The transcript is edited by Bunmi Ishola

Highlights from Quick to Listen: Episode #273

Before we talk about residential schools, what type of relationship did First Nation people have with Christianity, missionaries, and some of these denominations prior to the formation of the schools?

Jimmy Thunder: I want to talk about how Christianity came into my family. I’m from Sachigo Lake First Nation and originally, we had someone came to our First Nation and just share Christianity with us. The name has been passed down as ᒥᔥᑕᑾᓀᐟ (Mishtagwanet) but being that we know that it was an Anglican missionary we think that the name is probably something closer to Mr. Garnett. That is how my great grandfather came to know Christ and that was passed onto my grandfather, my father, and now to our generation.

The difference in this situation is, there was an invitation, there was a relationship and there was an understanding that we are equal in the eyes of God. The motivation was love and just a desire to share Christ. So, if we back up though, and we look at trying to answer the question to what does the relationship between Christianity and indigenous peoples look like? And I think that a lot of times we start with residential schools, but that wasn't really the start of the problem because it wasn't the start of the relationship.

When we look at the Royal Commission report on Aboriginal peoples, which was given to us in 1996, it paints out our relationship in four broad stages. And I think that gives us a good framework to talk about it. In the first stage, we're separated by an ocean and we're just basically separate worlds unaware of each other.

In the second stage, they call it peaceful nation-to-nation relationships. During this stage, you see cooperation, you see fair trade, you see treaties made between indigenous and non-indigenous peoples. A good example of that is the Two Row Wampum treaty that was made between the Haudenosaunee and the Dutch.

In that treaty, there are two lines of beads, which represent two nations and two boats that are traveling together, respecting each other and not harming each other for as long as the sun shines, grass grows and rivers flow. The third stage talks about colonialism and respect, giving way towards domination, to use their words, and then fourth to use a modern vernacular word; reconciliation.

So, these four stages help us to understand. But when we look at specifically the Christian context, it's important for us to look back at where this came from. I think the problem could be drawn back earliest to the doctrine of discovery and terra nullius. And so, these came from these papal bulls that were issued by Pope Nicholas the V and Pope Alexander the V fifth around 1455 and 1493.

When we think about that timeframe, those who are familiar with church history will know that that's shortly before the 95 theses and before the Reformation. If we think, what were the reasons for the Reformation? Why did we need to change? Well, part of it was because of this adjoining of church and state where you use Christian authority to get the will of the state met.

So, this is where the doctrine of discovery and terra nullius come from because, during the Age of Discovery, when we're looking for reasons to defend taking these “new lands” they use Terra nullius and the doctrine of discovery. So, terra nullius, “terra” means land and “nullius” means void or empty.

And so basically it was a teaching that if indigenous people were not Christian and they're not farming, then they're not really human and they can be considered as flora and fauna moving on over the land. And so, the land is free for discovery for the people that discovered it first. I think this teaching is the origin of all the problems that followed, for the 500 or so years that passed.

Because if you move forward, it's really difficult for us even today to think of what the First Nations actually were. If we try to name one of the nations, I think most Canadians can't do it. It would be really difficult for them to name what these nations were or to describe how their governments work or the distinction between First Nation law and Aboriginal law; First Nation law being our own ways of governing ourselves and Aboriginal law being what laws Canadians use to govern Aboriginal people in Canada.

All of that really stems from this idea that we were not people, we didn't have governments, we weren't self-determining and we were just flora and fauna moving in both the land and sea.

Were the explorers going to their church leaders and essentially asking for justification, seeing as you were saying, there wasn't a separation of church and state? Were they looking to the church for this type of permission?

Jimmy Thunder: Yeah, I think it's important to know that there's a mixture. I'm just describing where the problem is coming from overall, but yeah, in the same way that we have the Reformation, you do have Christians that are looking at this in the context of scripture, they're looking at the teachings of Jesus and saying, these motivations of our settler society are not in line with scripture.

And you did have people that were whistleblowing and sounding the alarm and that kind of a thing. But largely the biggest problem is the status quo, the trust for leaders, the comfort of just going with the flow of settler society and that's why we see a lot of the problems that we see today. A good example is when Canada first became a nation, it began with four different provinces. Instead of becoming a unitary state, they chose to have a separation between the federal and provincial government. The reason was because Canada recognized the diversity that it had; Protestants, Catholics, you have different languages. And so, this separation was meant to preserve the self-determination of the different provinces and to provide a mechanism for it.

As Canada expands and as more provinces join, that mechanism protects the self-determination and the cultural preservation of all the different provinces that join. When you compare that with how it interacts with indigenous peoples, you have nations that are nations and not colonies.

And you have the ability to do something very similar to preserve the language, to preserve the self-determination and the self-governance of those nations, which is exactly what the indigenous people understood the treaties to be doing, but we see something very different because even though self-determination and the preservation of language and culture was promised at the very same time, we see the Indian act that was unilaterally rolled out in 1876.

And as we know today, residential schools are a part of the Indian Act. It's one of the policies of the Indian act and the purpose of residential schools was to assimilate. It was to kill the Indian in the child. It was to basically take all of these treaties and sort of erase them from the public record because if you assimilate each individual First Nation person one by one, then there's nobody that you really have to hold to your treaty obligations to. And so that’s in a nutshell the big picture of why we are where we are today.

So, from what I understand about all of this, the Canadian government reached out to these different denominations to operate the residential school system. Is that correct? And if so, why did the government do that?

Jimmy Thunder: Yeah, they actually did, that is correct. The residential school system is actually a product of the United States. And in that case, there was a partnership between churches and government. And so, they were trying to implement that into Canada as well. It was sort of a case where Christians were willing partners in order for this to take place. And again, I think it's largely because the Christians of the day didn't really question the goals and beliefs of settler society against their Christian ideals and the scriptural teachings of Jesus.

What do you think was going through the heads of these different Christian leaders as they were running these residential schools?

Jimmy Thunder: I think that there's a variety of things because I think that we do have to recognize that when we're talking about the Christian involvement in those schools, there's a variety of different denominations, different people and so when we look at the harm that was caused you have a number of people that were causing the physical and sexual abuse, but those people did it again and again causing a huge amount of damage. So, you have those, and then you have other people that are maybe aware of what's going on; aware that these schools are being mismanaged and aware that they're underfunded and that children are not getting enough food.

But they're not acting on it, and there are various degrees of their awareness of that. But still overall for whatever reason, they chose the status quo as just something that's more comfortable and then you have other people that are almost unaware of what's going on; hearing different things, but not questioning it. So, to ask what's going on in their minds and their hearts, I think it's really very similar to human nature.

I think for a lot of Christians at the time what was going through their heads was that they were being told to do this but were not going to question it. They were not going to go step out of their comfort zone and question the status quo.

And I think that as much as that was a problem then I think that we see some of that even happening today as well.

A few years ago, we had the truth and reconciliation process. Can you tell us a little bit about what is happening now in the last few weeks and months that we didn't know after the Truth and Reconciliation Commission? Was it that that ended and that we still didn't know where some of the children were buried? Is it that there's a new revelation with discovering some of these graves?

Jimmy Thunder: Yeah, there's a couple of layers to that. I think that sometimes the easiest way to understand what's happening on a national level between nations is to think about how we process things as individuals and even in the context of a family. So sometimes as kids we will do something to cause harm to another child, but then we can apologize and we can say I am sorry, get forgiveness and then move on.

But as we get older, there are much more severe and increasingly difficult challenges to get through and reconciliation between people can be incredibly challenging and incredibly complex. And if we think of something traumatic that can happen between individuals, even when something serious like murder takes place, it's a long process and it's not as easy.

And when there's something really deep to go through, then sometimes a reminder of unresolved pain can be incredibly difficult and almost something that needs to be reworked through. Part of what we're seeing on the indigenous side is when we see the discovery of these unmarked graves in the one context starting with the 215 that were discovered in Kamloops, there are people alive who have been to residential schools and part of that is sort of triggering that memory all over again. Especially those people who had been searching and wondering what happened to the people that they went to school with that they haven't seen since then. Part of them were thinking well, maybe they're okay. Maybe they're alive somewhere. But to see 215 near a residential school, it's almost like confirmation that these individual people that I knew, that's probably where they are. And it's a revisiting of that feeling that they first felt when they had left.

And so, when we discover this, the pain is just as real as if it just happened just that week. So, it's 250 in funerals because you know for sure where they are now and it's fresh, those people haven't aged a day, they're still that age and they will always be that age. So, recognizing that for them in that community. It triggers everybody who's been touched by that trauma and that legacy because the residential school system happened for almost as long as Canada has been in existence, from 1876 all the way to 1996 and residential schools existed before they were part of official Canadian policy.

So, it hit a lot of people and the kinds of things that have happened in residential schools’ things that I'm hesitant to even mention here because they're triggering. But if you look at the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s final report and you look at what happened to children, it's unbelievable. It triggers all that emotion, all over again on the indigenous side. For the unindigenous people there, even though we have had this report since 2015, a huge number of Canadians have not read the executive summary of the report and a few of them have read the 94 calls to action or are familiar with it. So, for a lot of people, this is new information for non-indigenous people. It just raises questions for them on how to respond to this.

What is the response that you're hearing from nonnative Canadians? Is there an eagerness to engage? As you have engaged Christians on this, through the Evangelical Fellowship of Canada and others, how much hunger are you hearing to engage this and how much are you having to draw people in and convince them that they need to pay attention to this?

Jimmy Thunder: When the Kamloops discovery first happened, I got a lot of phone calls and texts from a lot of people who knew that I was speaking to this issue, wanting to hear and asking how can they help or what can they do?

I found that incredibly encouraging that out of something like this there is a significant group of Canadians and Christians that sincerely want to know what happened and what can I do about it? And so those are the people that I've really been paying attention and time to. I know that there's a lot of people out there that are still questioning the legitimacy of these discoveries and trying to downplay the need to look at our history and that kind of thing. But for me personally, I don't spend any time or energy on those people.

What I am really encouraged by, and what I'd like to do is really engage with people that are solution-focused and who believe in a better Canada and want to really explore how the teachings of Christ can be applied at this time and at this stage.

A lot of these schools were a part of a very ecumenical group, you have Catholic schools, Anglican schools, Presbyterian schools, the United Church. Obviously, you're working with the EFC, the Evangelical Fellowship of Canada and breaking in a number of Evangelical contexts. I'm wondering if evangelical Christians are engaging with this history and these revelations in different ways than non-evangelical Canadians? I'm wondering if there's some sort of Baptist being like, this is kind of their problem, but we have things we can do to heal wounds or do evangelical Christians feel implicated as well, even though they're kind of denominational families didn't run some of these schools.

Jimmy Thunder: Yeah. I see, I see a mixture. I know that there's a lot of people that their default is to say things like, well, this wasn't my denomination and then they'll probably name another denomination that was, or they might say something really simple, such as the people that were running these residential schools, weren't actually Christians.

So, this is an oversimplification of the problem, but then you also see other Christians that are openly saying it's the name of Christ that is implicated here. And even some of those newer denominations that weren't around yet say we're still involved in this and we still need to take ownership. We've all inherited this and we need to work together as Christians to solve the problem and to be Christ's hands and feet.

I think what I'm seeing now is an increased interest in the evangelical community that I haven't really seen before. I've been doing this for a number of years so I find that particularly encouraging.

Since we are talking about if Christians are engaging this issue, from what I understand about part of the settlement agreement, there are denominations that actually have responsibilities that they have to do as a result.

Jimmy Thunder: For those who are not really familiar with the settlement agreement what happened was all of the residential school survivors got together and they filed a class-action lawsuit against the Canadian government. It was the largest class-action lawsuit in Canadian history.

And it involved the Assembly of First Nations and a number of provincial-territorial organizations and residential school survivors. They won the case and as a result, the settlement provided five different elements to address the legacy of residential schools.

The first was the Common Interest Payment, which is eligible for all students of the Indian residential schools. There also was an Independent Assessment Process and that was a challenging process where residential school survivors had to recount their experiences in order to facilitate their compensation for the abuse they faced.

Third was support for healing initiatives. And the fourth was commemorative activities, we heal by commemorating and we heal by remembering. The fifth was the establishment of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission and I think that's a really big one because the work of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission was to travel all across Canada, collecting the stories of residential school survivors in order to document them and to provide a solution of how do we move forward together.

I think that there's nothing more powerful than actually hearing that truth. When we go back to that analogy of reconciling between people who've experienced incredible wrongs, we looked at the truth and reconciliation model which comes from South Africa. In that situation you had the perpetrators and the victims actually in the same spaces, working things out together. In Canada, we can't really do that because the problem is so huge and so deep and a lot of the original perpetrators and victims are no longer with us, but the effects of what they did are still with us.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission gave us a final report for over 4,000 pages long. Recognizing that that's a lot for people to read they gave us an executive summary, which is about a 10th of that. Even then they said let's create 94 specific things that people can do in order to make this better.

These 94 calls to action are meant for all segments of society, some for government, some for churches, some for the media, some for businesses. But the idea is that they're stepping away from the Royal Commission Report on Aboriginal Peoples that we had about 20 years later in which they had a 20-year plan, but it was all directed towards the government.

The biggest problem at that time was that Canadians weren't aware of what was in that report and what the recommendations were, or that a 20-year plan even existed. So, 20 years came and went. So, this time around, they said, let's shift the focus to all of Canada and let's make reconciliation something that we all have to have a part of doing.

We all have to learn about what happened and we have to learn about how we can fix things. And so today, as people are trying to process these discoveries and they're asking the questions of what we can do, the 94 calls to action are a great way to begin because these are 94 things that you can do now that are concrete, that will actually commit to change and moving towards reconciliation between indigenous and non-indigenous peoples.

The media coverage still seems like it's largely framed in terms of government response. But I'm curious to know if evangelicals see some of those calls to action as personal calls to action or are people assuming that most of those calls to action are about government response and money that's not necessarily their money.

Jimmy Thunder: Yeah, I think that is a common misconception that we're trying to break. One of the things that I'm doing with our organization; Reconciliation Thunder, we're partnering with another organization Circles for Reconciliation and in response to the Kamloops discovery, we've been posting one call to action per day for 94 days to try to get people to actually read each call.

In doing that, you can actually see what these calls are and who they're directed towards. Part of the reason for the misconception is that there are calls to the government that are in there and a lot of them are right up at the front and so if you do a cursory skim or the first couple of calls, then you'll see we are calling on the government to do this or calling the federal government to do that.

Without reading all the way through you don't see the variety of the calls and who they're directed to and what the actions are. So, this is something that we're actively trying to change; to change that misconception that these are not calls exclusively to the government.

There was a point when the Canadian government committed to executing all 94 of the calls to action which was a bit ironic, given that all of the calls to action are not aimed towards government.

Can you give us an example of a call to action that a Christian without a lot of government power would have? What have they been called or asked to do?

Jimmy Thunder: There's a couple of different ways. I could look at that. So, for example we've know that Christians are not just a Christian they have different jobs and work in different places in different parts of society. So, there are calls to action that are given just towards Christians.

One of the calls, I think it's called Action Number 59 is for church leaders to have education strategies for the congregation for them to learn about the history and legacy of residential schools and to learn why apologies to survivors were necessary and to work towards reconciliation within their denominations.

Education strategies are really important because without knowing what the history is, you can't understand the truth that's so necessary for us to move forward together. So, educate your congregation.

There's a lot of terms and phrases that repeat themselves in the different sections. One of them is the reference to UNDRIP; the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. That document it's about 42/ 43 articles that set out the minimum standards for the survival, dignity and wellbeing of indigenous peoples worldwide, so teaching your congregation what that is and unpacking that from a Christian lens. So that's from a church base. Christians also do other things in society, so call to Action 92 is for the corporate sector.

With my business background you can unpack that. Basically, it's about four or five different sub-points. Part of it is to look at the section of UNDRIP as it relates to resource development. Resource development can take place without the free prior and informed consent of the indigenous peoples who live in the area that you want to develop.

So that's one component of 92. Another component is to provide cultural awareness training, anti-racism training and educating people on the history and legacy of residential schools. If you look at all the five different points in Call to Action 92, it's really just about you as a company, being a better manager, looking at your corporate social responsibility and just setting up your company in a way that facilitates reconciliation between indigenous and non-indigenous peoples.

I want to talk a little bit about the First Nation community. What does the Christian community look like today? And how is it also wrestling with the legacy of residential schools?

Jimmy Thunder: Yeah. I guess the indigenous Christian community is very varied. You have within the context of indigenous, you have First Nation, Métis, and Inuit. Within the context of First Nation, you have Cree, Oji-Cree, Dene, Saulteaux Mohawk and so on. There's such a huge variety of what that is and what that looks like. That of course lends itself to its diversity of Christian traditions. I think that Christianity worldwide wherever Christianity exists, there's a little bit of a cultural reflection in terms of how Christianity presents itself in that culture and I think in indigenous cultures that's no exception.

In Canada, we have the North American Institute for indigenous theological studies and that's the leader in conceptualizing, in contextualizing the Christian faith into indigenous cultures. I say indigenous cultures, because again, there is that huge mix. There are different ways of taking different practices, different ceremonies, different spiritual understandings and you use that to contextualize the Christian faith. There is a huge variety because different people are comfortable with different things and so that's true between indigenous and non-indigenous Christians and it's true between indigenous Christians themselves.

There is a variety of what people are comfortable with contextualizing and how they understand their Christian faith in the context of their cultural identity.

Speaking more specifically with regards to your own community that you're a part of, how have you as a community been working through some of this most recent news coming up from the residential schools?

Jimmy Thunder: In Sachiko Lake, we have the minister that I quoted earlier Mr. Guanet whom we assume is Mr. Garnett; he was an Anglican missionary, and we also had another missionary that came in; John John Spillenar, he was Pentecostal. We have a couple of different Christian traditions in the one community and it's really small.

In that context, you see the sort of the diversity. There isn't always an alignment in terms of how we express ourselves but there is respect and I think that's the key thing, respecting each other's different journeys I think that's incredibly important.

I'm currently working out of Winnipeg, Manitoba, and I'm working for Norway House Cree Nation. There is a lot of hurt in the community that I'm with right now in current events, a lot of revisiting of traumatic experiences, heavy hearts and but just pair that up with the recognition that people are listening and also recognizing that the former chair of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, Murray Sinclair said that if it took us 150 years to get in the mess that we're in, it's probably going to take 150 years to get out.

The reason for that is that there there's a lot to learn, there's a lot of work that needs to be done, there are some systemic shifts that need to happen in our government. And there's a recognition of having more Canadians understanding the solutions that have already been found and that exist.

Within our Christian community, we have a diversity of different perspectives on how we express our ourselves spiritually, but all of us, I think, would be in alignment that our history is important and paired with our understanding of who God is and what God's sense of justice, the guiding of God's truth and God's love; those things together are going to be the path for us to get out of this and to move into right relationship with each other.

One of the things that I just honestly struggle to comprehend when I read these accounts of the abuse and trauma that people experienced in residential schools is why there are still First Nation people that are Christians. Have you met any of those survivors who have still embraced their faith and what have they told you about why they've decided to remain committed to God?

Jimmy Thunder: Yeah, my uncle is a residential school survivor. Aside from residential school survivors, there's also day school survivors and Sixties Scoop survivors and even just people who have been through the CFS system. There are commonalities in all of those different experience because in a large part, it's a government policy of assimilation and an attempt to remove our culture from who we are and to erase that sense of identity. Its cultural genocide found in all these different forms. In the case of my uncle, because of the trauma that he experienced he doesn't talk about it that openly. It's something that he really holds to himself. For a good portion of his life, he hasn't been dealing with it in a healthy way, but recently he's been able to overcome and get on his feet but a believer all the way through. What I've heard from him and from day school survivors is the recognition of who God is and who Jesus is, and this understanding that what was portrayed to them in the schools are not truly who God is.

And I think even for me personally I learned about the history a lot later in life, I learned about residential schools and really the depth of what happened, reading through the final report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in my twenties. It was a lot for me to process as well and I think for a lot of Christians even whether you're indigenous or not this understanding that Christians were involved in this, but also recognizing your personal relationship with Christ and who He is and who you understand God to be; those two things create a cognitive dissonance that is something that we all have to really work through.

I've heard it explained that reconciliation needs to happen on a nation-to-nation level, but also group to group, person to person and intra-personal. And I think for us as Christians, we have to process we have to really struggle through that problem of recognizing that the church is made of imperfect people and there was an opportunity and a chance for us as Christians to do something different, but we didn't. But where do we go from here? And I think that part of it is just wrecking, recognizing the depth of the problem is the first piece, but also just trusting that God is just, God is love. And that you know, as we continuing to learn and to journey together and to listen to each other, there is a way out and we can reconcile this and we can fix this. It's going to take a lot of time, but we can do it. And I think that that hope is not only what, what allows us to remain Christians, but it helps us to deal with that huge amount of cognitive dissonance that so many people just want to just avoid.

Ted Olsen: This is one of the big issues that we're wrestling with broadly, that we've always wrestled with that the church as an institution full of really broken people, being led by very broken leaders and often led poorly and that have lent themselves to abuse and the church also as the body of Christ Himself that this is somehow God's plan for the world. This is how He wants to act in the world. That to me is a constant mystery, it's both glory and shame in a lot of ways.

I am interested in another version of the question that Morgan asked, which is how to have some of the First Nations Christians who experienced some of this they're not just committed to Jesus, the person, the God of the universe, but also remarkably to these institutions that have caused great abuse, pain scarring and have been the opposite of Jesus in some cases.

But I'm wondering if there are special things that the First Nations experience has learned. We mentioned before that there's different views about kind of inculturation, but I'm wondering if there are certain theological focuses as it relates to the doctrine of the church or the doctrine of Jesus working through broken people that First Nations Christians are particularly talking about and are particularly bringing into conversations with groups like the Evangelical Fellowship of Canada and some of these groups?

Jimmy Thunder: I think that’s a huge struggle for a lot of people problem of evil, how does God allow evil to happen in the world as a result of people's free will and also recognizing that the churches are institutions and I think that when we forget that churches are institutions and governed by people and that people make choices on how church governance structure works that's a huge problem. I think that we need to remember that God calls different people to ministry, but people make decisions and He lets people make decisions in terms of our governance and even how the church is run organizationally. Churches don't like to think of it, but you do need to have strong HR protocols. You need to have human resources, policies, and procedures to protect your people and in the absence of those, damage happens and that's true even when we're not talking about indigenous issues, but incredibly important when we are talking about indigenous issues, when you're talking about how your organization is run, you need to have a conflict resolution policy that recognizes that you can't just change things because someone's indigenous and you can't change things because we're talking about reconciliation and it makes you uncomfortable.

You make a plan that you have your policies and procedures that reflect your biblical teachings and that holds you to that and when we forget to do those types of things, then it just opens the door for perpetuation of spiritual violence. And spiritual violence is something that is mentioned very specifically in the Truth and Reconciliation Commission and in the 94 Calls to Action.

A lot of times when people think of indigenous law, they just think of Canadian laws that govern indigenous people. But that's not what I'm talking about. I'm talking about the laws that existed pre-contact because we did have societies like a number of different societies, different government systems that we used to govern ourselves for thousands and thousands of years. And so, in these particular systems, we have different symbols and different things that give authority to our institutions in the same way that in the Canadian or American governments, you have strong symbols that sort of hold everything together. In Canada, you have the symbol of the monarchy and you have belief in God as creator, that is still one of those symbols that are there. And so, in indigenous law, you have this understanding of the Creator as the Sacred Creator that's present in your different laws and your institutions and so the sense of sacredness works its way into, into everything, including the law. An example of law is a treaty so when you're making a treaty between two different nations, the law is passed through the ceremony. So, for example, a pipe ceremony, that's when a pipe is passed around, as deep discussions take place. You burn the sacred tobacco and it's believed that the sacred tobacco carries that conversation up to the Creator. So, it's a tripartite agreement, between the creator and the two different parties. And it's also relationship-based. It’s not liked our treaties where it's the written word on the paper and that exists for all time.

Treaties are believed to take place for us all the time, but you revisit the terms. They are stored and commemorated on different objects, like the Two Row Wampum belt that I talked about or a feather or something else. And so, you just remember that as long as the relationship exists, you can revisit the terms, but it's the relationship that matters.

And it's held in place by the understanding of the sacredness of creator and its creators watching you implement these terms. When we think about it from that context it's impossible to really take advantage of someone using that legal system because its relationship-based and it's based off of a good relationship.

When you bring that into our Christian faith and how we understand as Christians, how to do life well together, you borrow the idea of Christian covenants because we see that in the Old Testament where God creates covenants with people and people make covenants with each other and God's involved.

And so, when we bring that idea into this relationship and into the church, we see a much more holistic picture of how to do life well together and there's a lot of blending and indigenous ways of seeing the world. There's not as spiritual and secular component it's all one seamless whole. And so, when we bring this together, then we see it becomes much easier to talk about solutions and goals because a lot of times, as Christians, we like to use the Bible as our compass for solving problems and not so much government tools and resources.

We like to just check out the 94 calls to action and UNDRIP and those documents, and we leave them outside the church and talk about them later. But you need to look at those from your Christian lens. And I think that's something that indigenous Christian leaders do. And I can bring into the conversation that gives us a better way of more holistically integrating solutions to the problems we see in our daily lives.

Jimmy, we started the show talking about these fires and it seems like there's been about half a dozen churches that have been set on fire or burned down. What has been your reaction to seeing this? What many people might believe is linked to these discoveries about these graves that are on the residential schools.

And many people feel like the fires may be coming in from that place. What is your reaction when you see these churches go up in flames and then also see the reaction from activists and leaders?

Jimmy Thunder: I would tend to join in with the indigenous leaders that are saying that this is not a healthy way for us to express our frustration and the very real pain that indigenous people are feeling. I think when you look for example at the top thing of the statutes that took place here in Winnipeg, I can understand completely the frustration of the people, I can understand the pain.

And I also understand what they're trying to communicate. The problem is when you're dealing with symbols, like a symbol of the queen it's not going to be understood by the greater public because with Canada, we're a constitutional monarchy. And so, when you, when you attack a symbol, people will interpret that as you were attacking the very structure of the government and you're instigating some type of anarchy.

But really for the people that I've spoken with, that are in favor of those types of things, it's a symbol of the legacy of colonialism and it's the residential school history and all of that is channeled toward that specifically, not the whole structure of what Canada is and who Canada is. In fact, it's the opposite, they’re trying to make Canada better. And so, you completely miss that entire message and so it makes it unhelpful and non-effective, and in fact, it gives fodder for those who would oppose the message and what we're trying to do. It just gives them a platform to maintain stereotypes against us as indigenous peoples. That carries true also for the church burnings as well. You understand the frustration, you understand the pain, you understand the depth of trauma that people are feeling. People died in residential schools and there's intergenerational trauma linked to that.

It's very real. And the frustration of people not listening to these stories and people not believing that we have these unmarked graves, we've been saying it from 2015 and way before that, the slowness of government, all of these different things. This frustration is expressing itself in these churches that are being burned.

And I think that it's very unfortunate and I would join the leaders in saying that it's an unhealthy way to express that. But I also want to just really remind people that, interpret this as an expression of the frustration, of pain and let's all be solution-focused and not let it detract from these good conversations that we're having about how do you fix things and how do we reconcile together as especially as Christians, we should be giving space for us to express what needs to be expressed in healthy ways and in a church context.

What do you think that the First Nation Christians have to teach those of us in the church who are not indigenous?

Jimmy Thunder: A lot of what I mentioned before about just let's look at things holistically. Let's look at what our Creator believes should be done. What does reconciliation look like according to our God let's not separate things.

Let's, let's look at our government reports, the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples, the Aboriginal Justice Inquiry, Truth and Reconciliation Commission, the missing and murdered indigenous women and girls panel report. Let's, let's look at these things, but let's bring them in then let's see how are our theology can guide us towards action, and let's not leave our history out of the equation. Let's work together. Let's look at what happened. Let's look at both historical records and the oral history that people bring, especially in the context of the treaties. Let's look at all these different things.

Let's put it together and let's talk about doing life better together.