Nowadays the worst part of being the youngest child is the hand-me-down clothes. But in the early Middle Ages, the youngest child couldn’t inherit land and often faced a life of hard labor as a serf. As the population grew, these landless serfs began to look for a better life beyond crowded feudal estates. Many took to the road as merchants.

Beginning in the eleventh century, the burgeoning merchant class created a market for education that went beyond learning about Scripture. While theology remained the “queen of the sciences,” merchants needed other skills: reading and writing, for communication with suppliers, and mathematics, for balancing books. As supply met demand, the university was born.

Universities became central to life in the Middle Ages. In addition to training and educating merchants, they also educated clergy, shaped public opinion on important theological issues, helped settle ecclesiastical disputes (including the Great Schism of the fourteenth century), and were alternately courted and threatened by power-seeking popes. Although largely unnoticed at the time, the universities also had a leveling influence in that they allowed poor men and youngest sons to gain power and status through education.

Medieval universities quickly gained popularity. By 1250, about 7,000 students attended the University of Paris. Oxford University, located in a much smaller city, boasted a very respectable 2,000 students. All told, 81 universities operated throughout Europe prior to the Reformation.

College Prep

Western Europe’s first schools were begun in the sixth century by Benedictine monks who wanted to teach young men to read and write. Because these schools were associated with monasteries, they tended to be in remote locations. Students spent most of their time learning Scripture and copying texts.

In 1079, Pope Gregory VII issued a decree requiring the creation of cathedral schools, controlled by local bishops, for the purpose of educating the clergy. These cathedral schools grew more influential than the older monastic schools, partly because they were located in growing cities, such as Paris and Orléans.

Universities arose from established cathedral schools, especially in France. Peter Abelard (1079-1142), a leading teacher in Paris, taught in a cathedral school on the bank of the River Seine. His enormous popularity attracted other teachers to Paris, and by the turn of the century the University of Paris had been founded.

The University of Salerno, begun in the ninth century as a medical school, is perhaps the oldest university in the Western world. Like other universities, it offered advanced instruction in subjects beyond the typical course of theological study in cathedral schools. The earliest ivies also included the University of Bologna (founded in 1084), Oxford University (1170), and the University of Paris (1200).

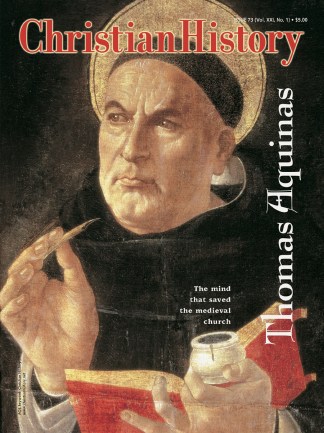

The University of Paris distinguished itself as the theological epicenter of Western Christendom, and its reputation attracted the best and the brightest. Albert the Great and his disciple Thomas Aquinas received theology degrees from the University of Paris in the 1240s. Nine future popes also studied there.

Up until the beginning of the thirteenth century, students from throughout Europe traveled to centers of learning, such as Cologne, Paris, or London, and sought out a master, or teacher. A student would arrive in the city, look for a place to live, and then attempt to hire a master to teach him.

Alexander Neckham, for instance, traveled from a small town near London to Paris in the 1170s. He studied under a fellow Englishman named Adam dou Petit Pont—French for “Adam of the Little Bridge,” because Adam taught in a house on the bridge across the Seine near Notre Dame.

Beginning in the thirteenth century, however, students and masters began to follow the example of the wider society and set up guilds. Guilds were associations of people who came together to create uniform standards for various industries and control membership requirements.

The University of Paris was born when students and masters grouped together into guilds and called themselves universitas (a Latin legal term for “a whole”).

With the arrival of guilds, anyone who hoped to become a teacher needed to complete six years of study in liberal arts. Individual universities added their own requirements as well.

The statutes for the University of Paris, written in 1215, stated that a new lecturer in the arts must be at least 20 years old and “is to promise what he will lecture for at least two years. … He [also] must not be smirched by any infamy.” Theology teachers needed an additional 8 (and later 14) years of education, and they also needed to be at least 35 years old.

In France and England, where students began their studies as teenagers, teachers played the major role in the university guilds, although Cambridge University gave students 15 days to decide whether to commit to a particular master. In Italy, where students were typically older, students had power to hire and fire teachers.

Old traditions, New ideas

Despite their uncertain career prospects, most teaching masters also enjoyed considerable academic freedom. The controversial John Wyclif, for example, taught at Oxford for 30 years before being forced out, in 1381. Not surprisingly, it was in the universities, where reason rivaled revelation, that challenges to church tradition began to arise.

Traditional curricula at monastery and cathedral schools consisted of the venerable Latin trivium—grammar, rhetoric, and logic—and the more advanced quadrivium—arithmetic, geometry, astronomy, and music. In addition, students learned medicine and law.

But all of this was before the Western world rediscovered Aristotle. As trade increased contact between the Christian West and the mostly Muslim East, Westerners bought back the works of Aristotle, which had been forgotten in the West for centuries. In the twelfth century, his works were translated into Latin, the lingua franca of the educated Western world.

Aristotle’s works sparked an intellectual renaissance as Aquinas and other Christian scholars sought to integrate Aristotelian and traditional Christian teachings about man and God. Their approach became known as Scholasticism, and it deeply influenced the subsequent course of Western philosophy. As universities spread throughout Europe, they quickly made the works of Aristotle central to their programs of study.

In addition to reading Aristotle, students were also required to study works by Gilbert de la Porre, Boethius, and others. Theological students, who often spent 14 years or more at university, devoted much attention to the Bible, patristic commentaries on Scripture, and the Book of Sentences, a textbook written by twelfth-century Paris master Peter Lombard (see page 33).

Almost from the outset, universities offered specialized courses of study. At Paris, Cambridge, and Oxford, students focused mainly on theology, church law, and liberal arts. Universities in Italy and southern France emphasized the study of Roman or Greek law and Arabic or Jewish medical texts.

Q-and-A Classes at medieval universities followed a fairly uniform pattern. A master read an excerpt from a standard text (Aristotle, for instance), then lectured on the standard commentaries on the text. Finally, he led a class discussion of the commentaries and the text itself. Students took notes on wax tablets, or less frequently on parchment. Paper cost far too much for everyday use.

Beyond lectures, disputation was the most popular learning tool at medieval universities. A disputation took place when two or more masters debated a text using the question-and-answer approach developed by Peter Abelard. Sometimes these disputations took place over several days. Debates between rival masters could last for years or even decades.

As a result of these disputations, the Western world developed a systematic understanding of the Christian faith. Many of the disputations centered on Peter Lombard’s Sentences. Aquinas, Bonaventure, Duns Scotus, and William of Ockham all wrote commentaries on the Sentences.

After three or four years of study, students were questioned orally by a master or a committee of masters. If the student passed his oral exams, he could become a baccalaureas, the equivalent of obtaining a bachelor’s degree. This entitled him to serve a master as an assistant teacher.

After another two or three years of study, the student took extensive written exams. If he passed, he earned an advanced degree, such as a master of arts. He then had the ability to become a university master, whereupon he hoped to be able to teach a student like Thomas Aquinas.

Matt Donnelly is a former assistant editor at Christianity Today International.

Copyright © 2002 by the author or Christianity Today/Christian History magazine. Click here for reprint information on Christian History.