"About a quarter before nine, while he was describing the change which God works in the heart through faith in Christ, I felt my heart strangely warmed."

In late 1735, a ship made its way to the New World from England. On board was a young Anglican minister, John Wesley, who had been invited to serve as a pastor to British colonists in Savannah, Georgia. When the weather went sour, the ship found itself in serious trouble. Wesley, also chaplain of the vessel, feared for his life.

But he noticed that the group of German Moravians, who were on their way to preach to American Indians, were not afraid at all. In fact, throughout the storm, they sang calmly. When the trip ended, he asked the Moravian leader about his serenity, and the Moravian responded with a question: Did he, Wesley, have faith in Christ? Wesley said he did, but later reflected, "I fear they were vain words."

In fact, Wesley was confused by the experience, but his perplexity was to lead to a period of soul searching and finally to one of the most famous and consequential conversions in church history.

Religious upbringing

Wesley was born into a strong Anglican home: his father, Samuel, was priest, and his mother, Susanna, taught religion and morals faithfully to her 19 children.

Wesley attended Oxford, proved to be a fine scholar, and was soon ordained into the Anglican ministry. At Oxford, he joined a society (founded by his brother Charles) whose members took vows to lead holy lives, take Communion once a week, pray daily, and visit prisons regularly. In addition, they spent three hours every afternoon studying the Bible and other devotional material.

Timeline |

|

|

1678 |

John Bunyan writes The Pilgrim's Progress |

|

1687 |

Newton publishes Principia Mathematica |

|

1689 |

Toleration Act in England |

|

1703 |

John Wesley born |

|

1791 |

John Wesley dies |

|

1793 |

William Carey sails for India |

From this "holy club" (as fellow students mockingly called it), Wesley sailed to Georgia to pastor. His experience proved to be a failure. A woman he courted in Savannah married another man. When he tried to enforce the disciplines of the "holy club" on his church, the congregation rebelled. A bitter Wesley returned to England.

Heart strangely warmed

After speaking with another Moravian, Peter Boehler, Wesley concluded that he lacked saving faith. Though he continued to try to be good, he remained frustrated. "I was indeed fighting continually, but not conquering. … I fell and rose, and fell again."

On May 24, 1738, he had an experience that changed everything. He described the event in his journal:

"In the evening, I went very unwillingly to a society in Aldersgate Street, where one was reading Luther's preface to the Epistle to the Romans. About a quarter before nine, while he was describing the change which God works in the heart through faith in Christ, I felt my heart strangely warmed. I felt I did trust in Christ, Christ alone for salvation, and an assurance was given me that he had taken away my sins, even mine, and saved me from the law of sin and death."

Meanwhile, another former member of the "holy club," George Whitefield, was having remarkable success as a preacher, especially in the industrial city of Bristol. Hundreds of working-class poor, oppressed by industrializing England and neglected by the church, were experiencing emotional conversions under his fiery preaching. So many were responding that Whitefield desperately needed help.

Wesley accepted Whitefield's plea hesitantly. He distrusted Whitefield's dramatic style; he questioned the propriety of Whitefield's outdoor preaching (a radical innovation for the day); he felt uncomfortable with the emotional reactions even his own preaching elicited. But the orderly Wesley soon warmed to the new method of ministry.

With his organizational skills, Wesley quickly became the new leader of the movement. But Whitefield was a firm Calvinist, whereas Wesley couldn't swallow the doctrine of predestination. Furthermore, Wesley argued (against Reformed doctrine) that Christians could enjoy entire sanctification in this life: loving God and their neighbors, meekness and lowliness of heart, abstaining from all appearance of evil, and doing all for the glory of God. In the end, the two preachers parted ways.

From "methodists" to Methodism

Wesley did not intend to found a new denomination, but historical circumstances and his organizational genius conspired against his desire to remain in the Church of England.

Wesley's followers first met in private home "societies." When these societies became too large for members to care for one another, Wesley organized "classes," each with 11 members and a leader. Classes met weekly to pray, read the Bible, discuss their spiritual lives, and to collect money for charity. Men and women met separately, but anyone could become a class leader.

The moral and spiritual fervor of the meetings is expressed in one of Wesley's most famous aphorisms: "Do all the good you can, by all the means you can, in all the ways you can, in all the places you can, at all the times you can, to all the people you can, as long as ever you can."

The movement grew rapidly, as did its critics, who called Wesley and his followers "methodists," a label they wore proudly. It got worse than name calling at times: methodists were frequently met with violence as paid ruffians broke up meetings and threatened Wesley's life.

Though Wesley scheduled his itinerant preaching so it wouldn't disrupt local Anglican services, the bishop of Bristol still objected. Wesley responded, "The world is my parish"—a phrase that later became a slogan of Methodist missionaries. Wesley, in fact, never slowed down, and during his ministry he traveled over 4,000 miles annually, preaching some 40,000 sermons in his lifetime.

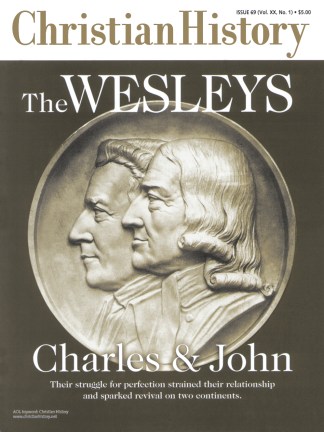

A few Anglican priests, such as his hymn-writing brother Charles, joined these Methodists, but the bulk of the preaching burden rested on John. He was eventually forced to employ lay preachers, who were not allowed to serve Communion but merely served to complement the ordained ministry of the Church of England.

Wesley then organized his followers into a "connection," and a number of societies into a "circuit" under the leadership of a "superintendent." Periodic meetings of methodist clergy and lay preachers eventually evolved into the "annual conference," where those who were to serve each circuit were appointed, usually for three-year terms.

In 1787, Wesley was required to register his lay preachers as non-Anglicans. Meanwhile, on the other side of the Atlantic, the American Revolution isolated Yankee methodists from their Anglican connections. To support the American movement, Wesley independently ordained two lay preachers and appointed Thomas Coke as superintendent. With these and other actions, Methodism gradually moved out of the Church of England—though Wesley himself remained an Anglican until his death.

An indication of his organizational genius, we know exactly how many followers Wesley had when he died: 294 preachers, 71,668 British members, 19 missionaries (5 in mission stations), and 43,265 American members with 198 preachers. Today Methodists number about 30 million worldwide.

Corresponding Issue