"Earnest prayers, long fasting, and burning tears may seem befitting, but cannot move the heart of infinite love to a greater willingness to save. God's time is now. The question is not, What have I been? or What do I expect to be? But, Am I now trusting in Jesus to save to the uttermost? If so, I am now saved from all sin."

For the century after John Wesley founded Methodism, conversion meant emotion, an intense religious experience lasting moments or days. It established one's salvation and was considered the absolute prerequisite of Christian perfection, or "entire sanctification."

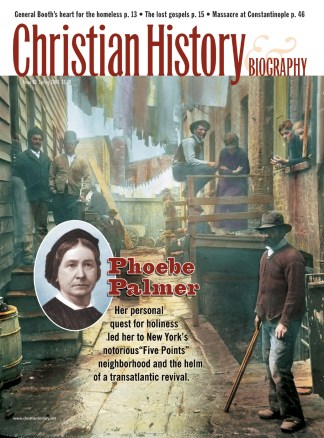

For years that was Phoebe Worrall's problem. Born December 18, 1807, to zealous Methodists who conducted family worship twice a day, she had never felt not a Christian.

Timeline |

|

|

1789 |

Bill of Rights |

|

1793 |

William Carey sails for India |

|

1806 |

Samuel Mills leads Haystack Prayer Meeting |

|

1807 |

Phoebe Palmer born |

|

1874 |

Phoebe Palmer dies |

|

1879 |

Frances Willard becomes president of WCTU |

At age 11, she inscribed a poem on the flyleaf of her Bible:

This revelation—holy, just, and true—

Though oft I read, it seems forever new;

While light from heaven upon its pages rest,

I feel its power, and with it I am blessed.

Henceforth, I take thee as my future guide,

Let naught from thee my youthful heart divide.

And then, if late or early death be mine,

All will be well, since I, O Lord, am Thine!

But still she had not experienced the "powerful conversion" (as she put it) as had her Methodist friends and family.

Her first decade of marriage to Methodist physician Walter Palmer didn't help. Their marriage was strong, but their first two children died mere months after their births. Phoebe was convinced God was punishing her for not totally devoting herself to him: "Surely I needed it, or it would not have been given," she wrote. "Though painfully learned, yet I trust the lesson has been fully apprehended."

A year later, while her sister was visiting, Phoebe's spiritual crisis was resolved. She didn't need "joyous emotion" to believe—belief itself was grounds for assurance. Reading Jesus' words that "the altar sanctifies the gift," she believed that God would make her holy if she "laid her all upon the altar." She divided John Wesley's perfectionism into a three-step process: consecrating oneself totally to God, believing God will sanctify what is consecrated, and telling others about it.

"I now see that the error of my religious life has been a desire for signs and wonders," she wrote. "Like Naaman, I have wanted some great thing, unwilling to rely unwaveringly on the still small voice of the Spirit, speaking through the naked Word."

Prayer meetings nationwide

Phoebe and her sister began women's prayer meetings each Tuesday afternoon—which, six years later, would include a male philosophy professor. Eventually, word of these successful prayer meetings inspired similar gatherings around the country, bringing Christians of many denominations together to pray. Phoebe soon found herself in the limelight—the most influential woman in the largest, fastest-growing religious group in America. At her instigation, missions began, camp meetings evangelized, and an estimated 25,000 Americans converted.

She herself would often preach, "Earnest prayers, long fasting, and burning tears may seem befitting, but cannot move the heart of infinite love to a greater willingness to save. God's time is now. The question is not, What have I been? or What do I expect to be? But, Am I now trusting in Jesus to save to the uttermost? If so, I am now saved from all sin."

Palmer was also deeply concerned about social ills. She was an ardent supporter of the temperance movement and one of the founding directors of America's first inner-city mission—New York's Five Points Mission.

A prominent religious woman in such an age was met with suspicion. Actually, she agreed with critics that it was not right for women to engage in "women preaching, technically so called." But, she added, "it is in the order of God that women may occasionally be brought out of the ordinary sphere of action and occupy in either church or state positions of high responsibility."

Such an example inspired other women, like the Salvation Army's Catherine Booth and the Women's Christian Temperance Union's Frances Willard.

Though she considered herself simply a "Bible Christian" who took Scripture with absolute seriousness, her theology is her legacy. Considered the link between Wesleyan revivalism and modern Pentecostalism, her "altar covenant" gave rise to denominations like The Church of the Nazarene, The Salvation Army, The Church of God, and The Pentecostal-Holiness Church.

Corresponding Issue