In this series

The problems facing persecuted faiths in the Middle East are too complex to be fixed by money alone. But experts are hopeful that doubling US assistance to Iraq’s Nineveh Plains, along with improved understanding of the region’s minority groups, will make a major difference for Christians returning there.

A year ago, Vice President Mike Pence pledged direct support to Christians, Yazidis, and other minorities forced out of their homelands in Iraq by ISIS. Religious freedom advocates and groups in the Kurdish region of northern Iraq cheered the news from a US administration that had long promised to prioritize persecuted believers, only to disappoint such groups when—due to bureaucratic hang-ups—the money didn’t come.

Now, the Trump administration has engaged leaders on the ground and doubled down on its promise to help. The government’s latest multimillion-dollar assistance plan, announced Tuesday, brings the total funding over the past year for religious minorities in Iraq to nearly $300 million, with allocations to rebuild communities, preserve heritage sites, secure left-behind explosives, and empower survivors to seek justice.

The announcement came just as Cardinal Louis Raphael I Sako, the head of Iraq’s Chaldean Catholic Church, complained that “there’s been nothing up to now” from the US.

But American efforts in the beleaguered region already show signs of improving.

The US Agency for International Development (USAID) “has been very slow in getting aid out the door, and it’s just starting to make a difference, with reconstructing schools, electricity switched on, etc., since mid-September,” said Nina Shea, director of the Center for Religious Freedom at the Hudson Institute.

Last month, USAID administrator Mark Green deployed Max Primorac, appointed as a special representative for minority assistance, to Erbil. His job is to help administer programs on the ground and address the kinds of problems that slowed the funding process earlier this year.

USAID also announced last week a new collaboration with the Catholic group Knights of Columbus, which joins 36 local, 11 faith-based, and 27 international partners in northern Iraq. They will “work together to identify those in need with greater precision; mobilize private and public sector resources to help them; and collaborate on efforts to prevent, and respond to, genocide and persecution in Iraq and across the region,” Green said. Knights of Columbus has given more than $20 million to the region since 2014, with plans to donate $5 million more over the next six months, Crux reported.

The new efforts in the region follow Green’s visit to Iraq over the summer with Sam Brownback, the State Department’s ambassador-at-large for international religious freedom.

The State Department’s first-ever Ministerial to Advance Religious Freedom ultimately led top officials to a more nuanced appreciation of the role of Chaldeans, Assyrians, Yazidis, and other persecuted minorities in Iraq, according to Chris Seiple, president emeritus of the Institute for Global Engagement (IGE).

“Whereas USAID provides aid that is faith- and color-blind, it now understands that there are times when it has to provide aid to groups who not only understand themselves as defined by their faith, but who were targeted for genocide precisely because of that self-understanding,” he told CT.

Seiple highlighted the new awareness in these remarks from Green during his trip in July:

We believe that religious pluralism, which is part of a cultural mosaic, we believe it is worth preserving as a matter of development, as well as an expression of our values. And one of the clearest cases for this work is in Northern Iraq. So, most Iraqis refer to minority groups as “component groups.” And I didn’t understand what that meant; I didn’t understand the significance. And someone came to me and said, “Well, that has a very special and powerful meaning in Arabic. It implies that Iraqi society is incomplete without the Christian and Yazidi components of that national mosaic.”

“This language of religious minorities as ‘components’—understood as necessary and enriching ingredients without which Iraqi society is less than whole—now animates the US effort to empower and enable religious minorities,” said Seiple, who made several visits to Iraq at the height of ISIS’s threat between 2014 and 2016.

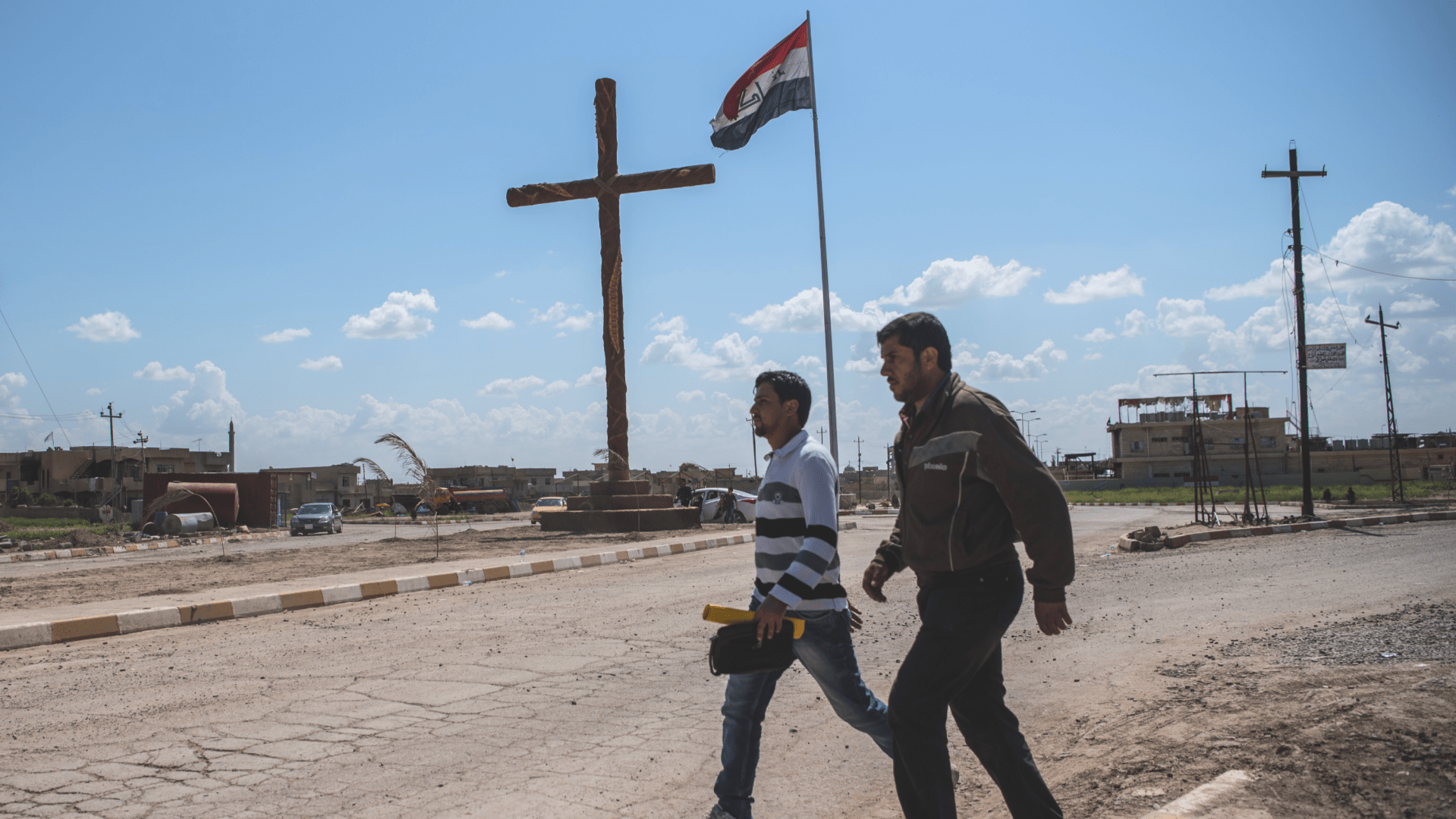

About 40,000 Christians who escaped those attacks have since moved back to their homes in Nineveh, despite the challenges that remain, World Watch Monitor reported this month.

“There is still much to be done, much to rebuild. The houses were damaged, burned or destroyed,” said Alberto Ortega, a Vatican diplomat in Iraq. “But now almost half of the Christians, in some places, who had left their homes, have been able to return.”

Back in 2014, Christian outreach to believers in the region began with a short-term emergency response, but “it became apparent to us that the overall scale of the challenge was sometimes beyond the capacity of regular, everyday people, and the ultimate solution had to be the type of assistance that could only be provided by governments,” said Johnnie Moore, who worked with TV’s Mark Burnett and Roma Downey on the Cradle of Christianity Fund, and now serves as a commissioner with the US Commission on International Religious Freedom.

“When we first started working with them there wasn’t a prospect at all of their going back to their communities. Those communities had been entirely taken over by the terrorists,” he said. “Now we need to help them restore our lives.”

The additional $178 million in US funding aims to help these returning families live safely and redevelop their communities, with the biggest allocations going toward humanitarian assistance ($51 million), economic revitalization ($68 million), and clearing explosives left behind by attackers ($37 million).

“Based on our long-term work with partners on the ground there, this plan for distribution is spot on,” Open Doors USA president David Curry said to CT.

“Their water supply has been sabotaged and they can’t plant their fields due to explosive devices embedded in them…,” he said. “Without large scale support like this, the Iraqi people will not be able to become economically healthy again and their people, who have no jobs, will not be able to sustain themselves long-term.”

In the town of Bashiqa, home to Christians and Yazidis, USAID has repaired homes, funded clinics, established 21 schools, and repaired wells to provide water for 12,000 residents, Green stated.

Experts have backed the overall plan, but are eager for more details from the US. Seiple said the approach resembles IGE’s strategy of “rescue, restore, and return,” but he would have liked to see more detail about particular programs, trauma care for women, and efforts to prevent future atrocities.

Similarly, Shea at Hudson said USAID needs to improve its messaging and provide a comprehensive list of projects and locations.

“I am thrilled to see this funding come. But be clear, this is only the beginning,” said Curry at Open Doors, which ranks Iraq as No. 8 among the worst places in the world for Christian freedom. “The success of recovery efforts rests in the ability of multiple world leaders and governments, as well as humanitarian organizations, to cooperate. It’s all hands on deck in Iraq.”

Even government officials know that their financing can only go so far. “… [T]he measure of progress is not in dollar amounts, it is in the lives and communities we have helped revive and restore, and in the concrete progress on the ground in Iraq's Ninewa Plains,” Green said in a statement on Tuesday.