Editor’s note: CT also offers a collection of tributes by leaders and friends of Padilla.

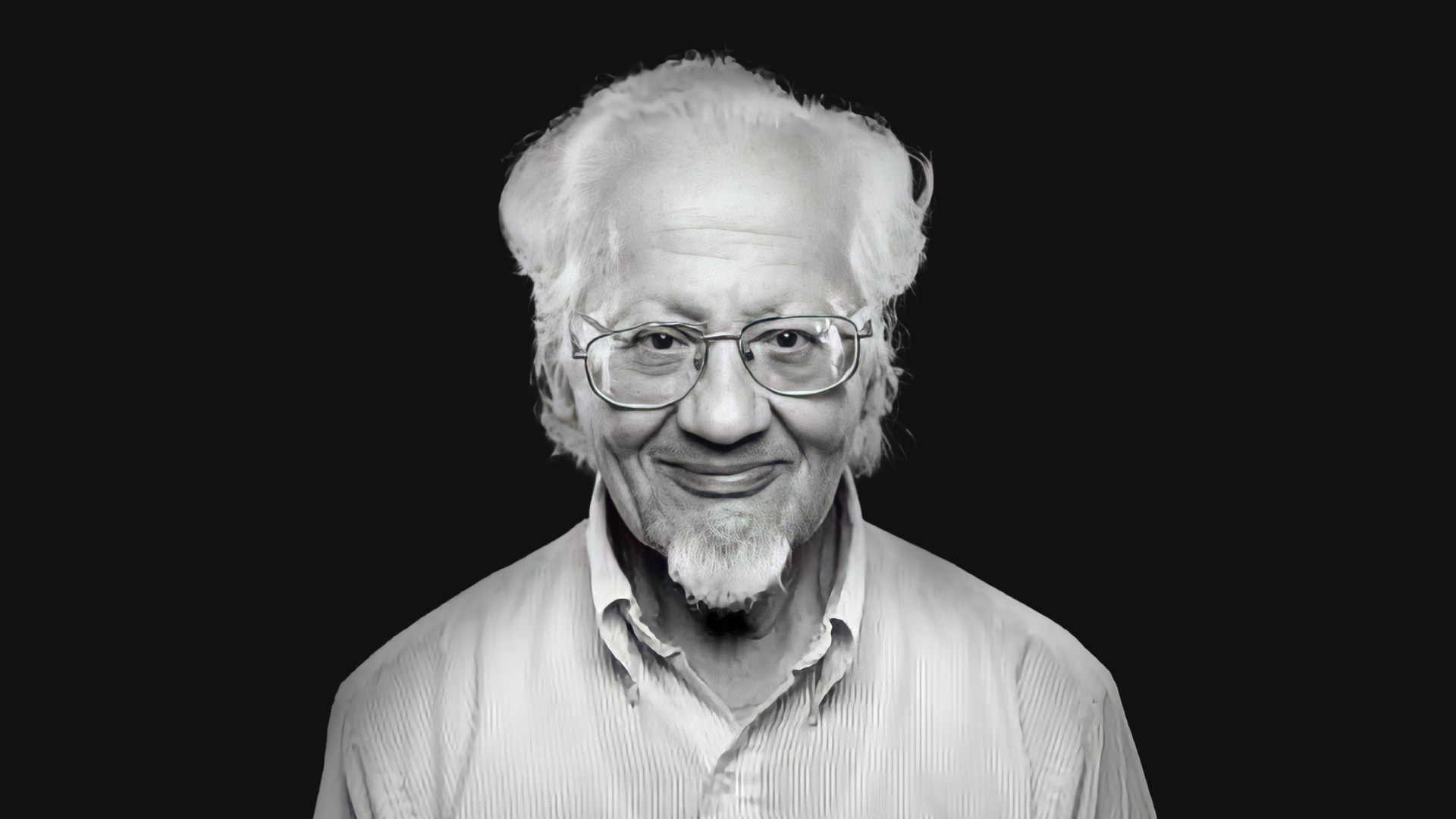

C. René Padilla, theologian, pastor, publisher, and longtime staff member with the International Fellowship of Evangelical Students, died Tuesday, April 27, at the age of 88.

Padilla was best known as the father of integral mission, a theological framework that has been adopted by over 500 Christian missions and relief organizations, including Compassion International and World Vision. Integral mission pushed evangelicals around the world to widen their Christian mission, arguing that social action and evangelism were essential and indivisible components—in Padilla’s words, “two wings of a plane.”

Padilla’s influence surfaced most prominently at the Lausanne Congress of 1974, where he gave a rousing plenary speech. Nearly 2,500 Protestant evangelical leaders from over 150 countries and 135 denominations gathered in Lausanne, Switzerland, at a meeting funded primarily by the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association (BGEA). One influential magazine called Lausanne “a formidable forum, possibly the widest-ranging meeting of Christians ever held.” When Padilla ascended the stage, he carried the hopes and dreams of many evangelicals from the Global South who sought equal footing in the decision-making of worldwide churches and mission organizations.

Padilla specifically called American evangelicals to repent for exporting the “American way of life” to mission fields around the world, devoid of social responsibility and care for the poor, making the case for misión integral.

A term drawn from his homemade whole-wheat bread (pan integral), it referred to a synthesized spiritual and structural approach to Christian mission, originally translated as “a comprehensive mission.”

“Jesus Christ came not just to save my soul, but to form a new society,” he said at Lausanne.

Padilla’s life story was surprising in its global reach—from an impoverished childhood in Colombia and Ecuador to sharpening evangelicals throughout the world. He ministered with American missionaries Jim Eliot, Nate Saint, and Pete Fleming before their untimely deaths outside Quito in 1956; he translated for Billy Graham crusades across Latin America in the 1960s; he shared intimate friendship and speaking tours with John Stott in the 1970s; he bridged a growing divide between a younger generation of evangelicals from the Global South and leaders in the United States and Great Britain in the tumultuous 1960s and 1970s; and he led global evangelical organizations. He also was published widely in theological journals and student publications such as that of InterVarsity Christian Fellowship (IVCF).

Much of Padilla’s legacy remains within Latin America among pastors, theologians, and lay leaders. While he was often offered positions in the United States, Padilla chose to remain in Latin America, pastoring among the poor, leading the Kairos Center for Integral Mission, and publishing hundreds of first-time Latin American authors through his Ediciones Kairos publishing house. Padilla also co-founded the Latin American Theological Fellowship (FTL) and the International Fellowship of Evangelical Mission Theologians and served as president of Tearfund UK and Ireland and the Micah Network.

Carlos René Padilla was born in Quito, Ecuador, on October 12, 1932. Padilla came of age alongside the American missionary community in the region, pioneering evangelism projects and translating US radio programs as a young teenager for the HCJB radio ministry. As a child, Padilla knew he was different, marked by a religious identity that was marginalized and excluded by a broader Latin American culture. Padilla’s father was a tailor to pay the bills but an evangelical church planter at heart. Both his parents became evangelical Christians before he was born, through the influence of Padilla’s uncle, Heriberto Padilla, who according to Padilla was one of the first evangelical pastors in Ecuador.

Church planting was a dangerous endeavor in the staunchly Roman Catholic Colombia, where his family moved in 1934. Their homes were firebombed, and multiple assassination attempts were made upon him and his father as they planted churches and performed open-air evangelism. Padilla bore scars from stones thrown at him as a seven-year-old as he walked down the streets of Bogotá, attempting to attend the local school.

Looking back, Padilla noted this was part of being a faithful evangelical Christian: “In Colombia you had to identify yourself as an evangelical Christian, and if you did, you had to pay the consequences.”

As an economic migrant and as a member of a religious minority community, Padilla was shaped by a context of violence, oppression, and exclusion. The relationship between suffering and theology was an organic one for Padilla. As a young person, he recalled “longing to understand the meaning of the Christian faith in relation to issues of justice and peace in a society deeply marked by oppression, exploitation, and abuse of power.” The question for Padilla was not whether the gospel spoke to a challenging Latin American context, but how. These questions drove Padilla to seek answers in theological education and practical ministry among college students.

As a teenager, Padilla flew in American missionary pilot Nate Saint’s plane over the Ecuadorian Andes. Saint, along with Jim Elliot and Pete Fleming, had recently organized an evangelical children’s Bible camp in a small town outside of Quito. As Padilla peered through the cockpit at the Amazonian jungle below, he recalled Saint’s advice: “You’re going to study theology—be careful not to take theology undigested.” When the three missionaries were killed by indigenous Waorani people in a failed evangelization attempt in 1956, Padilla was a student at Elliot’s alma mater, Wheaton College. Their sudden deaths made, in his words, an “enormous impact” on him at Wheaton.

After arriving on campus in fall 1953, Padilla sought out the help of the school’s president, Victor Raymond Edman, who had served as a missionary in Quito, working alongside Padilla’s parents with the Christian and Missionary Alliance. Edman supported his new student—who barely spoke English and was in debt from his plane fare—by helping him find a job and connect with campus resources. By 1959, Padilla had earned a bachelor’s degree in philosophy and a master’s in theology. But he graduated in absentia, as he was already on staff with the International Fellowship of Evangelical Students’ movements in Venezuela, Colombia, Peru, and Ecuador. (IFES is the global body that arose out of national movements such as the US-InterVarsity Christian Fellowship and the Universities and Colleges Christian Fellowship in Britain.)

From Latin America, Padilla also proposed marriage to his longtime American friend, fellow Wheaton graduate and InterVarsity staff worker Catharine Feser. He described his marriage proposal as explicitly twofold—to marry him and to marry Latin America. Her commitment to Latin America as a mission field would play a major role in their shared ministry. (She would ultimately reject the US and vow to never return.) Catharine edited nearly everything René wrote, including his Lausanne 1974 speech. She provided a crucial bridge between English language proficiency and native fluency.

Padilla’s new role came six months after Fulgencio Batista’s regime was toppled in Cuba by Communist forces loyal to Fidel Castro. The uprising woke up the region’s young people to the reality that American imperialism was not inevitable, and its success amplified nationalistic tendencies, casting widespread doubt on foreign ideas. Most evangelical theological materials in Latin America had little to say about the pull of Marxist ideologies. Returning from the American suburbs to Latin America’s tumultuous political context shocked the young Ecuadorian and threw into question his theological categories, particularly those imparted by his education at Wheaton.

Padilla’s discontent with existing approaches to ministry, mixed with student demand for social engagement, pushed him to explore innovative solutions in mission and theology. His widespread contact with universities and students within Cold War Latin America gave him a unique perspective. But practical ministry experience was not his only expertise. His evangelical education credentials gave him wider credibility to speak into theological debates, such as those at Lausanne.

From 1963 to 1965, Padilla completed his PhD at the University of Manchester under F. F. Bruce, Rylands Professor of Biblical Criticism and Exegesis, “the most prominent conservative evangelical biblical scholar of the post-war era,” as historian Brian Stanley later described him. Studying with Bruce made Padilla trustworthy to the broader evangelical world, ultimately leading to a speaking invitation at Lausanne and a partnership with John Stott, which would prove crucial to the later inclusion of social elements in the Lausanne Covenant.

In the 1960s and early 1970s, Padilla began to speak of Latin America’s theological poverty, lamenting that local questions were being met with foreign answers. Padilla joined forces with IFES colleagues Samuel Escobar and Pedro Arana, as well as missionary Orlando Costas, creating an eclectic coalition of restless theologians. Together, they shared experiences of living in unjust and unequal contexts during the Cold War and a frustration with how many evangelical organizations treated Latin Americans.

One such frustration occurred at the 1969 BGEA-sponsored “First Latin American Congress for Evangelization,” better known for its Spanish acronym, CLADE. The event was an attempt to help Latin American pastors and theologians see the dangers of Marxist-inflected theologies and to impose US theological categories upon the region. The BGEA had observed the seemingly unchecked advance of radical theological movements by prominent, first-generation liberation theologians, and commitment to traditional Protestant evangelistic mission had started to wane. But for the embryonic Latin American Evangelical Left, CLADE represented a resurgence of American evangelical paternalism and imperialism. Padilla called the conference “made in the USA” and said paternalism was “typical of the way in which work was done sometimes in the conservative sector.”

In response, Padilla, Costas, Escobar, and others founded Fraternidad Teológica Latinoamericana (FTL). The organization pushed Padilla to publish and produce answers to gnawing missiological questions, and its early years provided some of the most significant contextual theology for Latin American Protestant evangelicals, including Padilla’s book Mission Between the Times: Essays on the Kingdom.

Padilla was already gaining prominence and sharpening his critical voice even prior to Lausanne. In a 1973 article for Christianity Today—the magazine’s first article to directly address liberation theology—Padilla warned conservative evangelicals to address their own ideological biases before critiquing liberation theology. He also rejected liberation theology itself, while concluding, “Where is the evangelical theology that will propose a solution with the same eloquence but also with a firmer basis in the Word of God?”

In July 1974, Catharine Feser Padilla gathered her children around a world atlas in their home in the barrio of Florida Este in Buenos Aires. Her daughter, Ruth Padilla DeBorst, later recalled, “The tone of her voice had a certain unaccustomed urgency: ‘Today, when he gives his talk here, in Lausanne, Switzerland’—pointing to the city on the map—‘Papi will say some things that not everyone is going to want to hear. Let’s pray for him and for the people listening to him.’”

At the Lausanne Congress of 1974, for the first time, leaders from the Global South gained a place at the table of the world's evangelical leadership—bringing their emerging brand of social Christianity with them. Latin Americans spoke with a particularly strong voice, having honed their critique as a religious minority community. The editor of Crusade Magazine wrote that Padilla’s remarks “really set the congress alight,” and received “the longest round of applause accorded to any speaker up till that time.” Even Time highlighted Padilla’s speech in its coverage, calling it “one of the meeting’s most provocative speeches.”

Seizing momentum from his and Escobar’s plenary papers, Padilla, alongside John Howard Yoder, rallied an ad hoc group of 500 attendees they called the “Radical Discipleship” gathering that sought to further sharpen the social elements in the drafted Lausanne Covenant. After the congress, Padilla recalled their radical discipleship document as “the strongest statement on the basis for holistic mission ever formulated by an evangelical conference up to that date.” He also declared the death of the dichotomy between social action and evangelism in Christian mission.

Padilla’s presentation caused a stir. Stott, for instance, had previously rejected this view, but publicly reversed himself in his 1975 book Christian Mission in the Modern World. But it made many other evangelical leaders nervous, not only in North America and Britain, but also in the Global South. InterVarsity’s general secretary Oliver Barclay took issue with the heart of Padilla’s Lausanne presentation and later that year warned him of reaction to his paper in the “media” and attempted to rein in the young leader.

At Lausanne, Padilla had connected the mission of the church to the content of the gospel message itself—content that contained social realities. In doing so, he challenged the prevailing theology of mainstream Protestant evangelicalism that social action was an implication of the gospel message—not inherent to it. But for some, calling social ethics part of the gospel message unnervingly smacked of the social gospel and theological liberalism.

But for Padilla, embracing the wider gospel message was crucial for Christian mission. “The lack of appreciation of the wider dimensions of the Gospel leads inevitably to a misunderstanding of the mission of the church,” he said. “The result is an evangelism that regards the individual as a self-contained unit—a Robinson Crusoe to whom God’s call is addressed as on an island.”

In the following decades, Padilla helped shape the trajectory of the Lausanne Movement, leading colloquiums and conferences across the world. He continued to sharpen his message, including critiquing the role of the United States as a global power. His missiological legacy is perhaps most clearly seen in the documents of the Lausanne Congress in Cape Town in 2010. For the first time, integral mission was included in the official documents of the Lausanne movement.

Today, it is standard language for many evangelicals to speak of a wider gospel message—for individual, for neighbor, for creation. Beyond global gatherings, Padilla spent much of his time carrying out integral mission theological formation with pastors and lay leaders throughout Latin America through the Centro de Estudios Teológicos Interdisciplinarios (CETI), founded with Catharine in 1982.

Padilla was preceded in death by his lifelong colleague and first wife, Catharine Feser Padilla, in 2009. He is survived by his second wife, Beatriz Vásquez, and his five children with Catharine, Daniel, Margarita, Elisa, Sara, and Ruth, along with many grandchildren.