Hello, fellow wayfarers … How you can find community and sanity in the whirl of 2025 … Why you shouldn’t be afraid to be afraid … What the empty tomb explains about the universe and your life … How an ancient creed is needed more than ever … Houston, we have a Desert Island Playlist … This is this week’s Moore to the Point.

Christ Over Craziness

One thing I hear from a lot of you right now is that you feel like life is crazy. For many of you, it’s the news cycle that’s driving you crazy. Or it’s the sludge that comes over social media that makes you wonder if you are crazy. For some of you, it’s this time of shaking that the church and the world are experiencing that makes everything seem precarious and unsure.

Well, this Holy Week, I want to say a few things. Below are two “vintage” articles I thought you might enjoy.

The first is the abridged version of an essay I wrote five years ago—about why, at Easter, you should not be afraid to be afraid. I wrote this for CT before I came here, right at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, when the future seemed uncertain. It still does seem that way for other reasons—and it always will, for reasons we can’t even yet know. The second is from the early days of this newsletter, about how Easter is “natural” and how it is not—and why that matters for you.

But first, I want to ask those of you who haven’t yet subscribed to Christianity Today to join with me to get the full CT experience. What you’ll get is not just information and commentary but a community of Christians who believe the gospel should make us strange but not insane, connected but not tribalized, countercultural but not crazy.

This week, you can get two years for half the price at this link. That will give you:

- Unlimited access to insightful journalism, biblical perspectives, and rich theological insights that offer hope and direction in complex times.

- In-depth coverage of critical issues in the US and abroad—helping you navigate how to respond as a faithful follower of Jesus.

- Wisdom from trusted voices as they explore cultural conversations and ethical dilemmas through a biblical lens.

- Seasonal devotionals and access to 69+ years of searchable archives featuring notable Christian leaders and thinkers.

- Exclusive savings, including 15% off CT Store items and 50% off gift subscriptions.

Plus, you will help keep this newsletter and all our podcasts continuing to get to everybody for free.

Easter Fear Is Natural

At first glance, fear seems alien to Easter, belonging more to Good Friday. Even our hymnody reflects this. Good Friday’s “Were You There When They Crucified My Lord?” is in lyric and tune foreboding, while Easter’s “Up from the Grave He Arose” peals triumphant.

This makes musical sense. Good Friday evokes the emotions that the first disciples experienced when they thought all was lost and the noon skies above them turned dark. By contrast, Easter evokes a new dawn, the truth that everything sad is coming untrue.

And yet the Gospel accounts are not so neatly categorized by emotion. In fact, the first reactions to the resurrection were confusion and fear.

The guards at the tomb “trembled and became like dead men” at the sight of the angel there (Matt. 28:4, ESV throughout). To the faithful women, Mary Magdalene and the other Mary, the first words spoken by the angel were “Do not be afraid, for I know that you seek Jesus who was crucified. He is not here, for he has risen, as he said” (vv. 5–6).

Upon hearing the angel, the women were filled with “with fear and great joy” (v. 8). They then ran right into the risen Jesus, who repeated the angel’s words: “Do not be afraid” (v. 10). The earliest record of the resurrection, from Mark’s gospel, closes with the women fleeing the empty tomb, “for trembling and astonishment had seized them, and they said nothing to anyone, for they were afraid” (16:8).

One could imagine, of course, a less traumatic resurrection in keeping with the natural rhythms of the world—except that the resurrection was wholly unnatural, naturally eliciting fear and alarm.

The resurrection is not a timeless truth about the immortality of the human being, or the reassurance that everything works out in the end. The resurrection takes place in a graveyard—a reminder that, left to ourselves, every one of us will retreat to the dust from which we came. Thus, Jesus said to Martha, “I am the resurrection and the life” (John 11:25). He is the only one of us who has “life in himself” (5:26).

The resurrection of Jesus does indeed destroy fear, pulling us out of slavery from the fear of death (Heb. 2:14–15). But that freedom from fear does not come the way we usually pursue it, through denial and the illusion of immortality.

On the contrary, to see fully the glory and mystery of the resurrection of Jesus, we must feel the just sentence of our own deaths and the inevitability, apart from him, of our own demise.

The resurrection shows us our lives hidden in Christ, which means that on our own, we are the walking dead.

The resurrection means we follow Jesus where he went, toward where he is. “Whoever wants to be my disciple must deny themselves and take up their cross and follow me,” Jesus said (Mark 8:34, NIV). Easter is not the end of our carrying our crosses but the beginning.

This is terrifying when you think of it. And Jesus means for you to think of it. Only then can you listen to the shepherd who walks you through the valley of the shadow of death. Only then can you know what it means to know that “because he lives, all fear is gone.”

Death is awful, but death is defeated. The tomb is still empty.

Do not be afraid.

How the Empty Tomb Explains the Universe and Your Life

We all love a book which agrees with views we’ve long held. That can sometimes be a reason to suspect a book’s argument as confirmation bias, but not always. The question is whether the argument causes one to question all the shared assumptions, even if one arrives in the end at the same place one started.

That was the case for me with N. T. Wright’s 2018 Gifford Lectures, published in book form as History and Eschatology: Jesus and the Promise of Natural Theology. And while I will interact more with the book elsewhere, for now, I would like to point you to one argument Wright makes that is important for us to ponder during Holy Week: the resurrection of Jesus is (and is not) “natural.”

Now, it’s obvious how the resurrection is not natural. In nature, dead organic matter stays dead. The initial response to reports of the appearances of the resurrected Christ was disbelief for the same reasons that Joseph did not respond to Mary’s pregnancy with “It’s Beginning to Look a Lot Like Christmas.”

Nature—from all we can observe—is indeed red in tooth and claw. From what we can see, death seems to be a part of the circle of life. In that, the resurrection is a disruption of nature.

Without that disruptive aspect of the resurrection, people end up turning the resurrection into mere metaphor—of the memory of Jesus’ teaching in our hearts or of the ongoing community of the church in the spirit of its founder. The resurrection becomes pictured, then, not as an event in history but as a way of thinking about what we already know from nature, like how spring follows winter.

That natural reading of the resurrection, however, makes no sense of what we know from history—that a beleaguered and small band of disciples upended the Roman world with their claim that Jesus was bodily alive after his crucifixion and appeared to them in the flesh. And it is a contradiction of what the New Testament writings assert without ambiguity—that if Jesus is not physically and bodily resurrected from the grave, “your faith is futile and you are still in your sins” (1 Cor. 15:18).

Wright’s point in these lectures is that what has been called natural theology goes aground by attempting to argue from nature to an abstract God without reference to Jesus. Jesus is, in this model, “special revelation” only, to be addressed after we first build the foundation of God’s existence.

Wright correctly notes that this is wrong-headed for multiple reasons—one of which is that “we don’t even know what ‘divinity’ is until we discover who Jesus himself was, as all four Gospels insist.”

But the other problem is that we don’t know what nature is if we exclude history from it. And the incarnation—as well as the crucifixion and the resurrection—all happened in history. Jesus suffered “under Pontius Pilate,” as the creed affirms.

T. S. Eliot reminded us that “only through time time is conquered.” The gospel is not about something happening outside of history, but of a Son of God who entered our history, our nature, and freed us with his broken body and his poured-out blood. In that sense, Wright reminds us, there is no “nature” that can somehow avoid the Galilean.

Using the Emmaus encounter of the resurrected Jesus with the pilgrims, Wright shows how the signposts of the Old Testament Scriptures were misinterpreted on their own.

The signposts seemed to have been contradicted by the crucifixion. “However, the resurrection of the crucified Jesus compelled a fresh telling of the narrative, a fresh glance back at the signposts,” he writes. “And with that glance, in the light of the newly discerned dawn, the story turned out to be completed in a whole new way. The signposts were vindicated: Israel’s story had after all pointed in the right direction.”

Here, Wright appeals to Richard Hays’s model of “reading backward” the Scriptures—thus seeing how they all make sense in light of the kingdom of Christ.

As I was thinking about these questions, I could not help but think about Frederick Buechner and his admonition to “listen to your life.” Essentially, Buechner called us to pay attention—to what brings tears to our eyes, to what evokes awe and wonder, to what “coincidences” have made us who we are. These are all signposts of a sort, and they can all be misread. But if not read in the light of Christ, indeed, they will be misread.

Looking backward, we can see all sorts of ways that God was present in our lives—in ways we can only make sense of in terms of the gospel. The signposts are broken, yes, but when we follow Jesus, we find they were pointing in the right direction all along.

What’s a Real Christian, Anyway?

This week on the podcast, I talk to my friend, Glenn Packiam, about something that might seem really distant from you: the anniversary of the Council of Nicaea. It’s not a history lesson, but about something quite near to your daily life, answering the question of what it actually means to be a Christian.

How do we remind ourselves about what we believe? Why does all this matter?

You can listen here.

Desert island bookshelf

Every other week, I share a list of books that one of you says you’d want to have on hand if you were stranded on a deserted island. This week’s submission comes from reader Ed Taylor from Cypress, Texas, who writes:

I’m a retired contracts manager (gov’t contracts at that) for IBM Research. Happily married now for just over 50 years. My hobbies include reading, walking, working complicated Lego sets, visiting new places, and spending time with family and friends. I’ve also had the wonderful experience of teaching classes at my local church off and on for over 30 years and also got to teach at the University of Houston for 12+ years as adjunct faculty. BTW, I don’t consider Bible study/reading as a hobby but rather as a primary life pursuit.

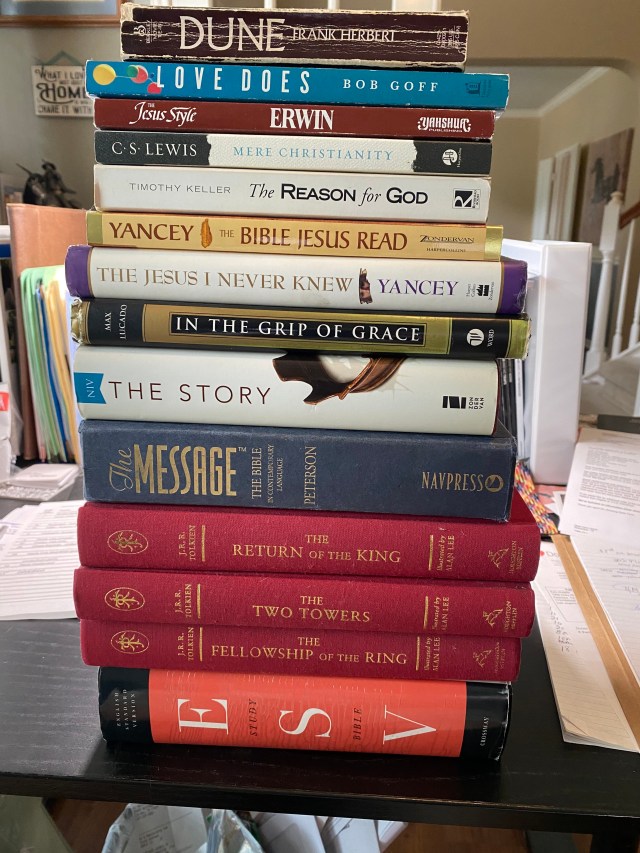

Here’s his list:

- The Bible has to top the list for all the obvious reasons, but primarily to facilitate the continued two-way communication with God I’ve enjoyed for over 50+ years. And the ESV Study Bible is my current go-to translation/version.

- The Lord of the Rings trilogy (J. R. R. Tolkien) is still the best fiction out there (IMHO). So far in the past 50+ years, I’ve read it through at least four times, with all but the first including The Hobbit. Could read it again every year.

- Eugene Peterson’s The Message is a delightful read, even if I don’t always agree with his theology.

- The Story (Max Lucado and Randy Frazee) is the best attempt I’ve read at trying to create a “seamless” chronological narrative of the Bible. And it helps me when I’m wading through the Old Testament and getting a bit lost in how it all ties together.

- Max Lucado’s In the Grip of Grace may be the best book written on the subject of grace since Romans. And I have had the privilege of teaching from it several times.

- Philip Yancey’s The Jesus I Never Knew helped me more clearly understand who Jesus really is and how that changed my perception of who I was in him.

- Philip Yancey’s The Bible Jesus Read, along with an Old Testament professor in college, really helped me come to grips with what it reveals about God and the fact that this is its primary purpose.

- Tim Keller’s The Reason for God: Belief in an Age of Skepticism, along with C. S. Lewis’s Mere Christianity, helped me fall in love with Christian apologetics and how it can help me with my doubts as well as provide tools for talking with intellectuals about their doubts.

- Gayle Erwin’s The Jesus Style gave me a richer, deeper understanding of the upside-down kingdom that Jesus ushered in and what it truly means to be “others-centered.”

- Bob Goff’s Love Does: Discover a Secretly Incredible Life in an Ordinary World continues to remind me of ways to think outside of the box in finding ways to love on people.

- Frank Herbert’s Dune may be the best sci-fi novel ever. I’ve read it several times and seen all of the movies so far.

Thank you, Ed!

Readers, what do y’all think? If you were stranded on a desert island for the rest of your life and could have only one playlist or one bookshelf with you, what songs or books would you choose?

- For a Desert Island Playlist, send me a list between 5 and 12 songs, excluding hymns and worship songs. (We’ll cover those later.)

- For a Desert Island Bookshelf, send me a list of up to 12 books, along with a photo of all the books together.

Send your list (or both lists) to questions@russellmoore.com, and include as much or as little explanation of your choices as you would like, along with the city and state from which you’re writing.

Quote of the Moment

“Were the early Christians with us now, they would still speak as men stunned by Christ’s crucifixion but shocked alive by his resurrection. The voice that declared ‘I am he that liveth and was dead’ (Rev. 1:18) they recognized and obeyed. … They would admit the complexity of problems in a world so largely given over to the Evil One. But they would be neither dismayed nor deterred by what so many modern churchmen consider an occasion for replacing reliance on Christ and the gospel with a resort to Caesar and to silver and gold to solve society’s deepest need.”

—Carl F. H. Henry (the first editor in chief of Christianity Today)

Currently Reading (or Re-Reading)

- Eric A. Havelock, The Muse Learns to Write: Reflections on Orality and Literacy from Antiquity to the Present (Yale University Press)

- Joan Taylor, Boy Jesus: Growing Up Judean in Turbulent Times (Zondervan)

- Thomas Merton, Mystics and Zen Masters (Farrar, Straus & Giroux)

- Jack Forstman, Christian Faith in Dark Times: Theological Conflicts in the Shadow of Hitler (Westminster/John Knox)

Join Us at Christianity Today

Founded by Billy Graham, Christianity Today is on a mission to lift up the sages and storytellers of the global church for the sake of the gospel of Jesus Christ. Why don’t you join us as a member—or give a membership to a friend, a pastor, a church member, someone you mentor, or a curious non-Christian neighbor? You can do so here.

Ask a Question or Say Hello

The Russell Moore Show podcast includes a section where we grapple with the questions you might have about life, the gospel, relationships, work, the church, spirituality, the future, a moral dilemma you’re facing, or whatever. You can send your questions to questions@russellmoore.com. I’ll never use your name—unless you tell me to—and will come up with a groan-inducing pun of a pseudonym for you.

And, of course, I would love to hear from you about anything. Send me an email at questions@russellmoore.com if you have any questions or comments about this newsletter, if there are other things you would like to see discussed here, or if you would just like to say hello.

If you have a friend who might like this, please forward it, and if you’ve gotten this from a friend, please subscribe!

Russell Moore

Editor in Chief, Christianity Today

P.S. You can support the continued work of Christianity Today and the Public Theology Project by subscribing to CT magazine.

Moore to the Point

Join Russell Moore in thinking through the important questions of the day, along with book and music recommendations he has found formative.

Delivered free via email to subscribers weekly. Sign up for this newsletter.

You are currently subscribed as no email found. Sign up to more newsletters like this. Manage your email preferences or unsubscribe.

Christianity Today is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

“Christianity Today” and “CT” are the registered trademarks of Christianity Today International.

Copyright ©2025 Christianity Today, PO Box 788, Wheaton, IL 60187-0788

All rights reserved.