It’s easy to feel like you know C. S. Lewis.

He’s the man who flung open the wardrobe door to Narnia. He introduced you to Peter the Magnificent and Lucy the Valiant; he won your heart through Reepicheep. And when Aslan roared goodness and beauty back into the world? You may as well have spent an evening in Lewis’s living room, listening to him talk wax lyrically on death and new life. Afterall, Lewis was an amalgamation of all of the best parts of his beloved characters. Wasn’t he?

While Lewis embodied many of these positive qualities, he also carried some of his characters’ less noble traits. This is something that’s easy to forget, or to want to forget, when reading his work. But the truth of Lewis is one of both doubt and faith, tremendous struggle and surety in salvation at once. The Lewis who gave you Caspian is also the Lewis who penned the petulant Eustace in need of transformation. He’s the creator of Edmund’s doubts and the White Witch’s rebellion. He is the weak and uncertain patient found in the pages of The Screwtape Letters.

Lewis dragged his feet on his way to kneeling at the foot of the cross. He argued against Christianity for years and rejected the concept of a God who had not answered his childhood prayers to save his mother’s life. When he finally surrendered to the truth of Jesus Christ, he did so as the most reluctant convert, one who still wanted to shake his head at Christianity’s claims but no longer could.

In seeing this whole picture of Lewis, you may find yourself meeting a stranger instead of an old friend. But perhaps you know him better than you thought. Maybe he, like you, is a person of both frustration and faith, doubt and devotion.

What if Lewis’s writing helped you understand your own faith because he wrestled mightily with his own?

Losing His Religion

Clive Staples “Jack” Lewis was born into a Protestant family in Belfast, Ireland, on November 29, 1898. His family loved books, encouraging Lewis and his elder brother, Warren, to read voraciously. An imaginative and bookish child, Lewis “pulled volumes off the shelves and entered into worlds created by authors such as Arthur Conan Doyle, E. Nesbit, Mark Twain, and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow.”

When Lewis was not yet 10 years old, his mother, Florence Augusta Hamilton Lewis, passed away from cancer.

“With my mother’s death,” Lewis wrote, “all that was tranquil and reliable disappeared from my life.”

Albert, Lewis’s father, could never fully recover from losing his brilliant, vibrant wife. Albert grew increasingly erratic and sometimes cruel in the years following her death, resulting in both C.S. and Warren feeling estranged from their father.

While studying at Cherboug House, a preparatory school for Malvern College, Lewis could not make sense of a God who had not answered his prayers for his mother’s life. The religious tone of his boarding school experience was one of harshness and, for a time, somewhat occultist. As a result of this doubt, rigidity, and darkness, Lewis forsook Christianity and became an avowed atheist at 14.

In 1917, Lewis began studies at Oxford, a place he would fall in love with for a lifetime. He served briefly in World War I, where he would suffer an injury from a bursting shell. He then returned to Oxford in 1919 and published his first book—a poetry collection entitled Spirits in Bondage—under the pseudonym Clive Hamilton.

Faith Comes Slowly

As they had in childhood, books remained an essential component of Lewis’s life and thought as he grew into adulthood. He found his imagination “baptized” by George MacDonald’s Phantastes. The Everlasting Man by G.K. Chesterton urged Lewis to reflect upon his materialism.

While MacDonald and Chesterton debated with Lewis from the page, friends like Owen Barfield and Nevill Coghill did so in the flesh.

“Rather like the texts of literature, a friend provides another vantage point from which to view the world,” wrote Colin Duriez in “The Way of Friendship.” “For Lewis, his different friends opened up reality in varying ways.”

Lewis struck up a relationship with J. R. R. Tolkien in 1926 after a meeting of the Oxford University English School faculty. In “Tollers & Jack,” Duriez describes their friendship as one that had an undercurrent of tension that would run beneath the pair's stream of mutual admiration. In fact, the first night they met, Lewis described “Tollers” as a man who had “no harm in him: only needs a smack or two.”

Over the next few years, Tolkien played an essential role in Lewis’s journey toward faith.

What Tolkien did was help Lewis see how the two sides, reason and imagination, could be integrated. During the two men's night conversation on the Addison Walk in the grounds of Magdalen College, Tolkien showed Lewis how the two sides could be reconciled in the Gospel narratives. The Gospels had all the qualities of great human storytelling. But they portrayed a true event—God the storyteller entered his own story, in the flesh, and brought a joyous conclusion from a tragic situation. Suddenly Lewis could see that the nourishment he had always received from great myths and fantasy stories was a taste of that greatest, truest story—of the life, death, and resurrection of Christ.

Like the creatures watching as Aslan ushered warmth and color back into a frigid, bare world, Lewis gradually began to see Christianity as a place he could inhabit with his whole being. He did not have to leave behind his logic, nor did he have to reject the comfort he found in epic tales rich with layered fascination. This merging of reasoning and imagination would be integral to Lewis’s belief in Christ and his later works, as noted in “Myth Matters” by Louis A. Markos.

Had Lewis brought to Christian apologetics only his skills as a logician, his works would not have been as effective. The mature Lewis tempered his logic with a love for beauty, wonder, and magic. His conversion to Christ not only freed his mind from the bonds of a narrow stoicism; it freed his heart to embrace fully his earlier passion for mythology.

In 1929, Lewis confessed on his knees that "God is God.” Over the next few years, he came to see “that the paradise he had been seeking was a false one.” Lewis had wanted joy itself, but that joy, he would realize, was not the endgame. The joy his soul desired would ultimately point him to the risen Christ.

“The impulse propelling Lewis toward an eventual conversion experience,” wrote Jerry Root, “was his quest to recover some object—comprehended only dimly, if at all—of his deepest longing.”

And so it was that in 1931, on a sunny morning drive to the zoo, Lewis became “the most dejected and reluctant convert in all of England.”

Making Sense and Story

In the years to come, Lewis would remain dear friends with J.R.R. Tolkien. They formed The Inklings, a literary group, and invited Lewis’s brother, Warren, and Charles Williams to join them. The group critiqued one another's work with the same intensity and tension with which Tolkien and Lewis had discussed faith. “Among the works-in-progress forged in the heat of friendly criticism,” wrote Robert Trexler and Jennifer Trafton, “were The Screwtape Letters, the Narnia books, and The Hobbit.”

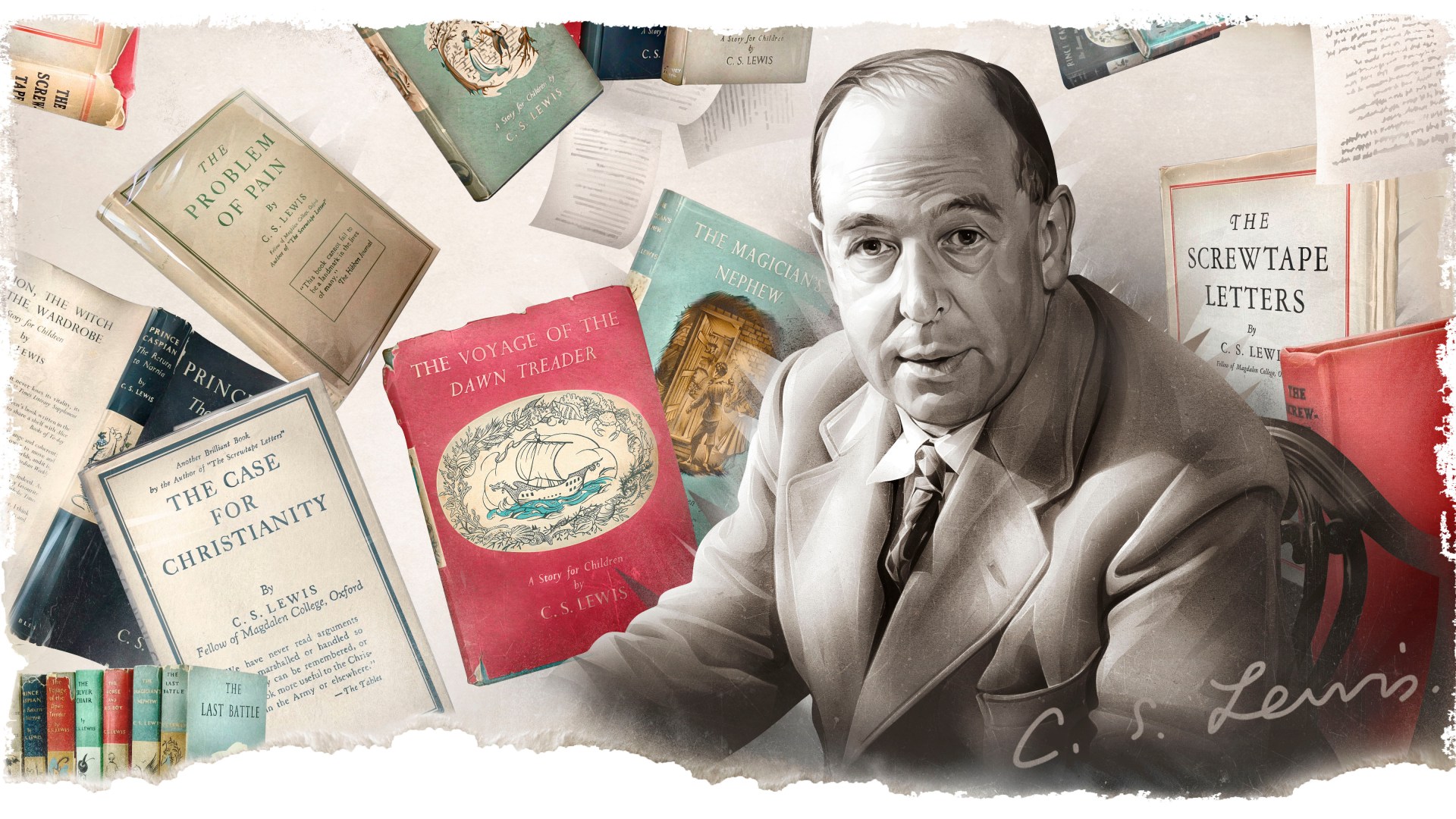

Between 1931 and his death in 1963, Lewis would go on to publish 34 books. His canon is a testament to his tumultuous relationship with both reason and imagination. He gave 25 talks on BBC radio, which would eventually become Mere Christianity, and he wrote other nonfiction, doctrinally minded books. But by the time Christianity Today invited Lewis to contribute to its first ever issue in 1955, he had turned his attention to fiction, devotional, and biographical material rather than direct theology. “I wish your project heartily well,” he wrote when he declined the invitation. And then he turned back to work on The Chronicles of Narnia series, work he would later describe as “casting all these things into an imagination.”

In fiction and fantasy, doctrine and devotion, Lewis described the tensions and triumphs of the Christian faith. He wrote with a compulsion to explore his own heart and mind, to make logical sense of his world and to paint it in the abstract. His way with words and wonder has drawn tremendous public interest—spurring biographies and biopics all attempting to better understand the man behind the pen.

Douglas Gresham was eight years old when he met Lewis. The son of Joy Davidman, Gresham would later know Lewis as his stepfather. In an interview, Gresham spoke of some of the qualities he loved most in “Jack,” about whom he wrote the biography Jack's Life: The Life Story of C. S. Lewis.

All too often, Jack's personality and his traits of honor, courage, duty, and commitment seem to get lost in the verbiage that clutters the pages of books about him. His wonderful sense of humor, his consciousness of his own sinfulness and of his salvation from it—these are missing from most writings about him, yet they were the essential characteristics of his personality.

Shadowlands also sought to portray the man behind the message, casting Anthony Hopkins in a 1994 film reviewed by Philip Yancey. Into this legacy of depiction enters The Most Reluctant Convert, an upcoming film that will trace Lewis’s spiritual journey for a new generation.

Starring Max McLean as an aging Lewis reflecting on his life, The Most Reluctant Convert is a thoughtful retrospective. The film follows the journey of a young Lewis, played by Nicholas Ralph, as he grows into a man of self-deprecating wit and remarkable talent, detailing his decades of reticence before giving his heart over to the one who made it. It’s in this Lewis, perhaps, that the friend you thought you knew will become more real than ever—simultaneously intent on the person of Christ yet stumbling toward eternity, just like you.

Abby Perry is a freelance writer who lives with her husband and two sons in Texas. You can find her work at Sojourners, Texas Monthly, and Nations Media.

Posted