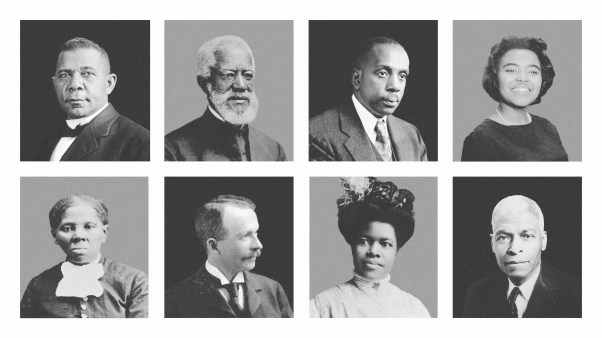

In 1968 our nation suddenly and unexpectedly lost its leading light on racial issues. I felt history repeating itself for me when I heard the news that Spencer Perkins had been taken from us. On January 27, the president of Reconcilers Fellowship in Jackson, Mississippi, and the son of evangelist/activist John Perkins died suddenly and unexpectedly of a heart attack at age 43 (see the obituary on p. 73).

In 1993 Spencer and his white ministry partner, Chris Rice, authored More Than Equals: Racial Healing for the Sake of the Gospel (InterVarsity). CT ran an excerpt about Spencer’s early struggle to assimilate two facts: one, that he was redeemed by Christ and, two, that many whites, allegedly redeemed by the same Christ, hated him (“How I Learned to Love White People,” Sept. 13, 1993, p. 34). He told of his despair when, at age 13, a white principal assented to a classmate’s judgment that Spencer was “just a nigger”; his pain at 16 when he saw the humiliation in his father’s eyes after John was ambushed and beaten almost to death for his civil-rights work; the confusion and hurt of being befriended and then rejected by a white college student. While his story of growing up black in America was powerful, it was not unique. The freshness came in his gospel-centered message.

For Spencer, the burden for racial reconciliation was heavy: “If white and black Christians could not be reconciled, then either the gospel was a lie or we really weren’t indwelt by the Christ we said had taken up residence in our lives.”

Yet this burden never provided an excuse to play down hard truths: “Most black people are angry—angry about our violent history, angry for the hassle it is to grow up black in America, angry that we can never assume that we won’t be prejudged by our color, angry that we will carry this stigma everywhere we go. … And most of all angry that white America doesn’t understand the reasons for our anger.” This anger can be “a very destructive force” or “channeled positively,” but it “must be reckoned with.”

In journalist Edward Gilbreath’s cover story on evangelicals and race 30 years after Martin Luther King, Jr. (see “Catching Up with a Dream,” p. 20), we hear more of Spencer’s hard truths: how segregation in the church is what both blacks and whites want, “but that puts comfort and culture over Christ.”

Lately Spencer talked about “radical grace” as the key to moving to the next step in racial reconciliation. But once again God has left it to us to finish the conversation without our group leader.

Copyright © 1998 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.