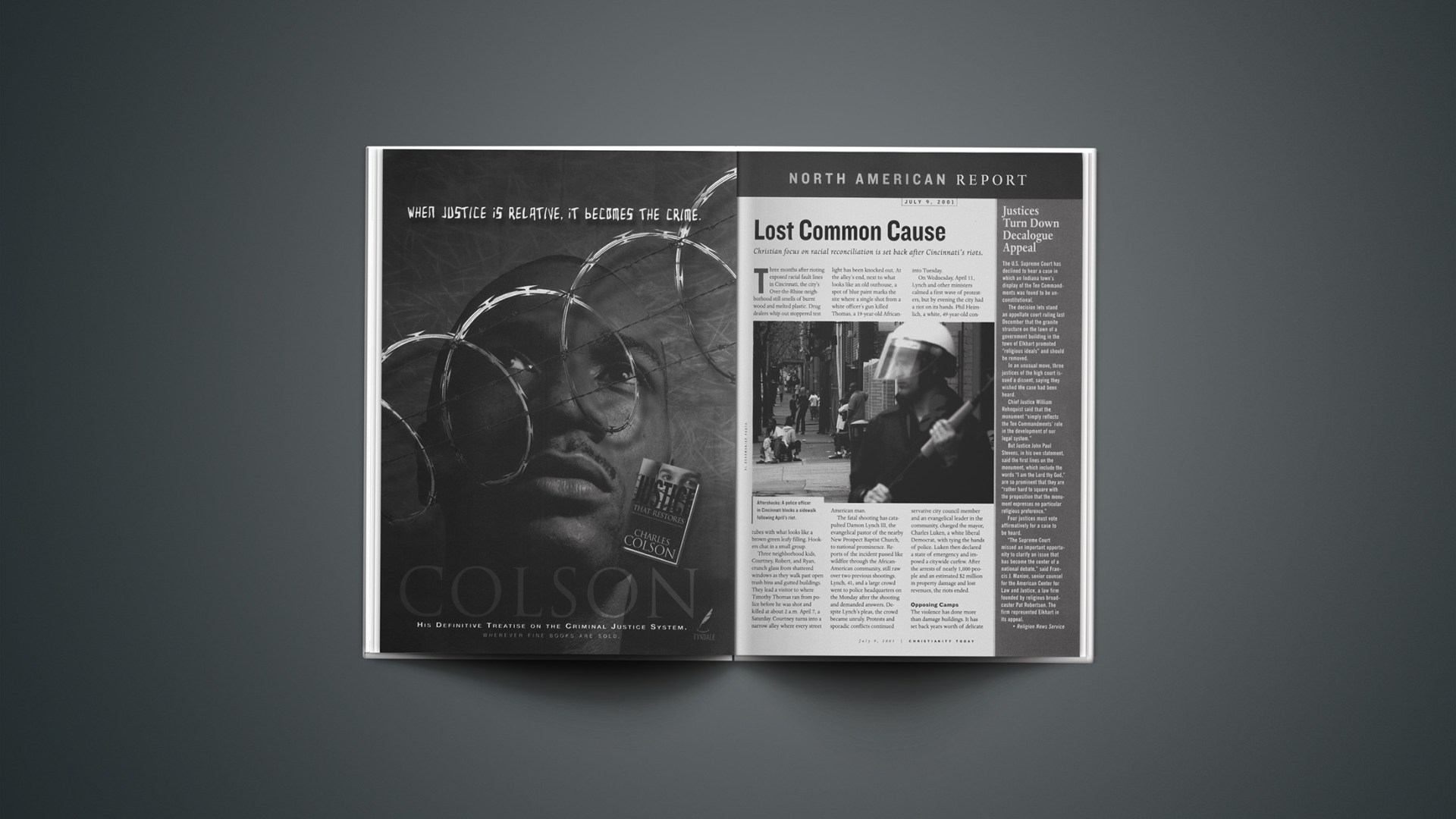

Three months after rioting exposed racial fault lines in Cincinnati, the city’s Over-the-Rhine neighborhood still smells of burnt wood and melted plastic. Drug dealers whip out stoppered test tubes with what looks like a brown-green leafy filling. Hookers chat in a small group.

Three neighborhood kids, Courtney, Robert, and Ryan, crunch glass from shattered windows as they walk past open trash bins and gutted buildings. They lead a visitor to where Timothy Thomas ran from police before he was shot and killed at about 2 a.m. April 7, a Saturday. Courtney turns into a narrow alley where every street light has been knocked out. At the alley’s end, next to what looks like an old outhouse, a spot of blue paint marks the site where a single shot from a white officer’s gun killed Thomas, a 19-year-old African-American man.

The fatal shooting has catapulted Damon Lynch III, the evangelical pastor of the nearby New Prospect Baptist Church, to national prominence. Reports of the incident passed like wildfire through the African-American community, still raw over two previous shootings. Lynch, 41, and a large crowd went to police headquarters on the Monday after the shooting and demanded answers. Despite Lynch’s pleas, the crowd became unruly. Protests and sporadic conflicts continued into Tuesday.

On Wednesday, April 11, Lynch and other ministers calmed a first wave of protesters, but by evening the city had a riot on its hands. Phil Heimlich, a white, 49-year-old conservative city council member and an evangelical leader in the community, charged the mayor, Charles Luken, a white liberal Democrat, with tying the hands of police. Luken then declared a state of emergency and imposed a citywide curfew. After the arrests of nearly 1,000 people and an estimated $2 million in property damage and lost revenues, the riots ended.

Opposing Camps

The violence has done more than damage buildings. It has set back years worth of delicate faith-based racial work. Many of the city’s Christian leaders, including Lynch and Heimlich, find themselves deeply at odds, accusing one another of promoting lawlessness or lacking compassion. Despite their greatly different backgrounds, Lynch and Heimlich have had much in common. They share the same spiritual mentor, Tom Smith. They met their wives at the same workplace. Their families have eaten together, and they share a commitment to solving urban problems.

Lynch talked to Christianity Today about the Over-the-Rhine neighborhood youth who started the rioting. Over-the Rhine’s decline has been a long time in the making. A century ago, it was home to 90,000 people. Today it has about 7,600, and 77 percent are African Americans.

As Lynch speaks, he seems to choose his words with great caution. He is given to long silences as he thinks things through. Lynch says that many of Cincinnati’s churches, turned off by urban youth with their gold chains and rap music, stopped reaching out to them. But Lynch has made a public commitment not to give up on youth in Over-the-Rhine. After the Thomas shooting, young people streamed to New Prospect Baptist Church, which opened its doors to them.

Lynch, who has led a series of sit-ins and demonstrations since the riots, positions himself as the person who can talk to rioters on the streets: “I reach them by offering to stand with them, in front of them and for them.”

But Heimlich, a former local prosecutor, shakes his head on hearing such comments from Lynch. Heimlich and others sense that Lynch’s agenda is more about politics than peacemaking. “Integrity means more than just telling the truth,” Heimlich says. “It means doing the right thing for the right reasons.”

Relations between Lynch and Heimlich have been increasingly tense since the riots. Heimlich has asked that Lynch resign or be removed as cochairman of the Cincinnati Community Action Now committee, formed by Mayor Luken after the riots. Heimlich says Lynch cannot be a reconciler at the same time he is engaging in civil disobedience.

Lynch’s father, also a minister, has denounced Heimlich, who was not selected for the committee and whose city council term ends in October. “You come off as one of the biggest hypocrites that I have ever seen,” the senior Lynch wrote in a fax to Heimlich and other council members. “I have tried my best to work with you over the years, but your record. . . is horrendous.”

The younger Lynch won’t repeat his father’s criticisms, but he is angry. “Phil is the not the devil that some people say,” Lynch says, “but he won’t be missed.”

Heimlich, working out of a spartan government office, under a photo of himself with Muhammad Ali, says he considers the late Martin Luther King Jr. a hero and role model for racial reconciliation. Heimlich has supporters in the black community.

Aaron Greenlea, head of the local African-American Baptist pastors council, says Heimlich has worked to bridge racial divisions in the city. “Phil really reaches out to the African-American community and focuses on some important issues,” Greenlea says. “Of course, we don’t agree on everything.”

Character and Accountability

Most Christian leaders in Cincinnati can agree on one thing: Costly government programs that “throw money at poverty” have failed.

While Heimlich emphasizes individual character more than Lynch does, they both support long-term, faith-based approaches to character development, entrepreneurship, and education. Both want to create an anti-crime program that improves the professionalism and accountability of the police force. They both seek to provide measurable improvements in the quality of life for poor people.

African Americans make up 43 percent of Cincinnati’s 331,000 people. Two-thirds of the city’s blacks fall below the poverty line. The jobless rate in greater Cincinnati is 3.5 percent. But in the Over-the Rhine neighborhood, it is about three times higher, around 10 percent.

In an interview with CT, Heimlich placed part of the blame for urban poverty at the feet of the city’s civil-rights leaders, saying they ignore the suffering caused by black-on-black crime and social irresponsibility.

Jaws clenched, arms wrapped tightly around himself, he leaned forward to hammer home his point: Corrupt civil-rights leaders broke their promises to build low-income housing. Heimlich notes that a local nonprofit housing program favored by some pastors in the civil-rights establishment took $800,000 of city money but built only one house and repaired a few others. Lynch has added his voice to the call for greater accountability in local social programs.

Eugene Rivers, a cofounder of a nationally acclaimed anti-crime partnership of African-American pastors and Boston police, believes Lynch is an important leader of the first new wave of the post-civil rights-movement black church leadership.

“He is not locked into the old wineskin paradigm of the brand name civil rights leadership,” Rivers says of Lynch. “He is much more programmatic and outcome-oriented. He doesn’t play to the old cliches, the old race card and victim sweepstakes.”

New Paradigm?

Former presidential candidate Gary Bauer recently visited downtown Cincinnati, four miles from his birthplace.

Bauer told CT that evangelicals in Cincinnati have an opportunity to build a new paradigm of race relations that can survive even intense political division. “If Cincinnati black and white Christians could make common cause with each other,” Bauer says, “they would be a political as well as moral force that would be hard for either political party establishment to deal with.”

The question remains whether Cincinnati’s Christian leaders will be able to move beyond their differences and work constructively on the city’s problems as brothers and sisters in Christ.

Heimlich says that Tom Smith recently called and prayed with him. “This pastor married me and discipled Damon [Lynch], too,” Heimlich says. “Eternal issues come first.”

Over-the-Rhine resident Michael Carter, 11, is doing his part. Responding to classmates who said they participated in the riot, he rapped a tune that his group, The God Squad, put together:

He’s the mender, the blender,

the Lord who brings together

the birds of different feather.

Say that again!

Copyright © 2001 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.

Related Elsewhere:

How civility turned to anarchy: The Cincinnati Enquirer examines the tensions leading to the riots.

In U.S. News & World Report, Baptist Rev. Aaron Greenlea says the turmoil is due to a lack of economic opportunity for young black men.

The week that tore Cincinnati apart worked powerful changes on the Rev. Damon Lynch III, according to TheCincinnati Enquirer.

Less than three weeks after the riots, about 1,000 people turned out for the Over-the-Rhine Neighborhood Potluck block party to help heal wounds, according to The Cincinnati Post.

The Cincinnati Enquirer reports on the formation of the Cincinnati Community Action Now.Cincinnati CAN’s official site has a bio on Lynch, and pdf Adobe Acrobat files of speeches made by the group. For more articles on the riots see Yahoo’s full coverage area.