Yet another book has crossed my desk bemoaning the sorry state of evangelicalism. And like many books before it, it highlights a number of scientific studies to prove it. The studies show that when it comes to rates of divorce, premarital sex, political bias, giving, or any number of social issues, “evangelicals” or the “born again” or “conservative Christians” (depending on the survey) are no better than the rest of America, and sometimes do worse.

These facts are usually followed by the dismayed evangelical author asking sometimes plaintively, sometimes prophetically: “Why does the church mirror the culture instead of lead it?” On the heels of righteous indignation come prescriptions and a pep talk. If the church would do “x”—something usually involving spiritual disciplines or church discipline—then the church would once again stand out as a city on a hill.

While we need prophets to exhort us to greater faithfulness, I tend to see such authors as inadvertent false prophets. I’m not thinking of the ones who lament our lukewarmness and then ask us to attend a $200 seminar to fix it. I’m thinking of the ones who are sincerely anxious about the state of the church. While their motives are good, their understanding of the church does not match Jesus’ description of it.

I’m troubled by these authors’ faith that statistics reveal deep realities of church life or spiritual growth—and by the sheer clumsiness with which they handle numbers. Christian Smith and John Stackhouse have already elaborated on this in articles in Books & Culture. My main concern lies elsewhere.

Their assumption that evangelical Christianity is supposed to be morally superior to other brands of the faith disturbs me. It shocks them when studies show we’re no holier than liberals, and that statistically, we often look no better than plain-vanilla pagans. Yikes! What they forget is that evangelicals are sinners, like the rest of Christendom. Evangelicals do some things really well—like evangelism. Other branches of the faith do other things really well—like social justice or liturgy. I believe classic orthodoxy will always sustain the church better than the experimental theologies liberals play with. But I’ve yet seen hard evidence that shows that when it comes to following Jesus day to day—doing the full spectrum of things he asks of us—we evangelicals do any better. As we follow, we’re stepping through the goop of self-centeredness like everyone else. It’s just hard.

Another assumption is that it is our job to make the church stand out from the culture, so that all the world will see what wonderful people we are and what a wonderful Savior we have. On the one hand, yes—God uses us to love and to perform good works that will cause some people to believe. On the other hand, he has never displayed his love in such a way that makes his presence plain to everyone.

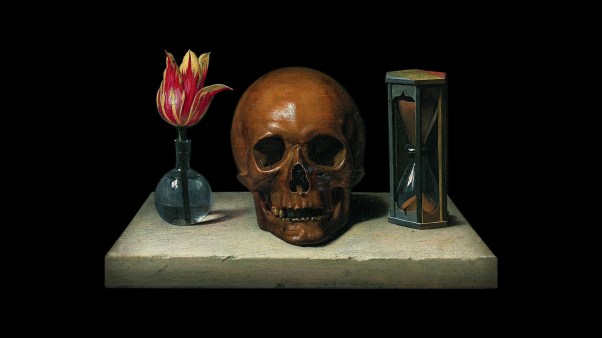

As Isaiah put it, “Truly, you are a God who hides yourself” (Isa. 45:10). He is the God who may have revealed himself in his law, but did so masked by dark clouds and thick smoke (Ex. 19:16-18). He may have come to us in Jesus, but he did so disguised, in the form of a servant, taking on flesh and blood. He didn’t reveal his love by confronting evil in an unequivocal display of power, but by dying in a way considered ungodly. So far, when God has come to us, we haven’t been able to pick him out of a crowd. Even after the resurrection—what more unambiguous proof do you want?—some still doubted (Matt. 28:17).

We know the church is the body of Christ in the world today, but why would we think that the world would be able to pick us out from a crowd of other well-meaning organizations? Indeed, “they will know we are Christians by our love”—that is, God works in and through the church to bring people to faith. But the evidence of history and the teaching of Scripture suggest that, this side of the kingdom, we are capable of such love only in fits and spurts. Even when evident, it is not always so evident.

The gospel is a treasure hidden in the field. It is the message given in perplexing parables, so that, as Jesus said, “They may indeed see but not perceive, and may indeed hear but not understand” (Mark 4:12). It is a message that will forever stupefy the educated, who look to it for cogent insights, and the pragmatic, who look to it to make a difference in the world: “For Jews demand signs and Greeks seek wisdom, but we preach Christ crucified, a stumbling block to Jews and folly to Gentiles” (1 Cor. 1:22-23).

Jesus said that in the church weeds would grow up right along with the wheat. He also said there would be people who would look devout—people who would pray, “Lord, Lord!” who would prophesy and cast out demons and do mighty works—and yet who would not have a stitch of faith. Indeed, many will say “I’m an evangelical” or “I’m born again” without knowing Jesus.

Rather than being shocked and appalled by surveys that demonstrate our moral mediocrity, we should yawn. We’ve known this for 2,000 years. Such studies tell us nothing we don’t already know. For his unfathomable reasons, God chooses to disguise himself when he comes to this planet, and there have been few disguises better than the church, a mystifying conglomerate of sin and love.

Yes, God transforms people, and many immoral lives are turned around by the power of the gospel. Sometimes it happens in an instant, but usually only after decades of struggle. The gospel remains the power of God to save. Yet in the church of the Crucified (versus the church of visionaries), we’re going to find a King David—that “man after God’s own heart” (Acts 13:22) who still dabbled in adultery and murder. We’re also going to see a lot of weeds. And a lot of pious people who display impressive religious behavior and proven effectiveness—what’s more effective than casting out demons or doing mighty works? —but don’t know Jesus.

Jesus told us not to judge who is in and out of the kingdom, lest we be judged. And he told us not to weed ahead of time, lest we pull out some wheat as well. Instead, he suggests we put aside our grandiose visions of what the church should be and learn to live in the church as the paradoxical thing it is.

That will mean, of course, that we’ll always mystify the scientific pollsters and visionary reformers. They’ll continue to point to survey after survey and conclude that the church looks pretty much like the rest of the world, and they’ll continue to wail and beat their breasts. That’s because they do not have eyes to see the treasure lying hidden in the cracked and decayed earthen vessel called the church.

Mark Galli is senior managing editor of Christianity Today. He is the author ofJesus Mean and Wild: The Unexpected Love of an Untamable God (Baker). You can comment below or on his blog.

Copyright © 2007 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.

Related Elsewhere:

Previous SoulWork columns include:

When a Blessing Is a Curse | Sometimes the most loving prayers are not all that nice. (August 23, 2007)

On Not Transforming the World | We have better and harder things to do than that. (August 9, 2007)

Grace—That’s So Sick | The church seems to be an embarrassment to everyone except its Lord. (July 26, 2007)

We Are Not Pregnant | The glory of men and women lies in their unbridgeable differences. (July 12, 2007)

Seeker Unfriendly | We need more than worship that makes sense. (June 14, 2007)

The Cost of Christian Education | Getting schooled in the faith is more unnerving than I care to admit. (May 31, 2007)

Surviving a Family-Wrecking Economy | What the church can do about working mothers. (May 17, 2007)

The Real Secret of the Universe | Why we disdain feel-good spirituality but shouldn’t. (May 3, 2007)

Peace in a World of Massacre | What Jesus calls us to when we’re most frightened. (April 17, 2007)

The Good Friday Life | We need something more than another moral imperative. (April 4, 2007)

I Love, Therefore You Are | Why the modern search for self ends in despair. (June 28, 2007)