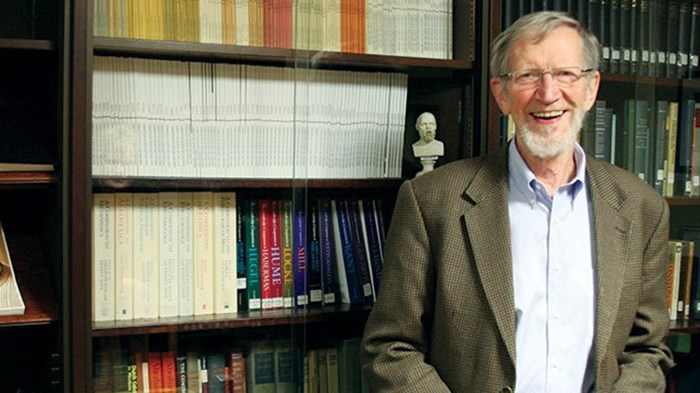

The man who brought belief in God back into the study of philosophy, Alvin Plantinga, has received the 2017 Templeton Prize.

The 84-year-old Christian philosopher is the latest in a line of dozens of laureates honored for their spiritual contributions to the world, including Billy Graham, Chuck Colson, Bill Bright, and Mother Teresa.

Plantinga made a name for himself as a philosophy professor at Calvin College and the University of Notre Dame. He reshaped the spiritual side of his discipline by insisting that Christian philosophers allow their convictions to drive their academic work.

“Plantinga recognized that not only did religious belief not conflict with serious philosophical work, but that it could make crucial contributions to addressing perennial problems in philosophy,” said Heather Templeton Dill, president of the John Templeton Foundation, which awarded the $1.4 million prize that has helped expand the evangelical mind.

Starting in the late 1950s, Plantinga countered the academic assumption that faith didn’t have a place in the field. Over decades of scholarship, he revolutionized how people view the relationship between religion and philosophy. Plantinga’s 1984 paper, “Advice to Christian Philosophers,” has shaped three generations of believers as well as religious philosophers across traditions.

Plantinga has received accolades “for his work in the philosophy of religion, epistemology, metaphysics, and Christian apologetics.” Since 2000, he focused his study on the compatibility between religious belief and science—the subject of a 2011 interview with CT.

Among his seminal works were God and Other Minds: A Study of the Rational Justification of Belief in God (1967), which prompted a renaissance of Christian philosophy and theism in the American academy, as recounted in a 2008 CT cover story by apologist William Lane Craig.

Called “America’s leading orthodox Protestant philosopher of God” or even “the greatest philosopher of the 20th century,” Plantinga’s explanation of free will “is now almost universally recognized as having laid to rest the logical problem of evil against theism,” Templeton noted. Plantinga’s “Warrant Trilogy” explores the rationality and justification of believing in God.

John G. Stackhouse, professor at Regent College, described Plantinga’s profound impact through defending faith against the common criticisms of the day (something he has continued to do in recent years):

Plantinga, then, has established the intellectual grounds for Christians to continue to believe in God, and particularly the God of historic orthodoxy, in the face of the two most daunting philosophical challenges of this century. He has done so, however, in distinctly 20th-century fashion. He has not, that is, offered a theodicy, an explanation for how God does, in fact, run the world. All Plantinga has done is show that it is not contradictory to believe that God is good, that God is all-powerful, and that evil yet exists.

In response to the Templeton honor, Plantinga remarked that he would be pleased if his work played a role in transforming the field of philosophy over the past several decades. A former president of both the Society of Christian Philosophers and the American Philosophical Association, Plantinga said he hoped his honor would “encourage young philosophers, especially those who bring Christian and theistic perspectives to bear on their work, towards greater creativity, integrity, and boldness.”

Plantinga grew up in Michigan, with a strong heritage in Dutch Calvinism. He began wondering about the big questions that would later shape his career—understanding evil in a world ruled by an omnipotent God—as a pre-teen in Dutch Sunday school classes.

After two semesters at Harvard University, he returned to Calvin College and went on to doctorate studies at Yale University. During his career, he also taught at Harvard University, the University of Oxford, the University of California–Los Angeles, the University of Illinois, and the Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences in Palo Alto, California.

A former Kuyper Prize winner, Plantinga recently weighed in on this year’s Tim Keller controversy at Princeton Theological Seminary.

He will receive the Templeton prize in a public ceremony at The Field Museum in Chicago on September 24.

CT’s sister publication, Books & Culture, ran Plantinga’s response to Pope John Paul II’s Faith and Reason 1998 encyclical, as well as covered the 2010 retirement of “Big Al” from Notre Dame, which drew 200 philosophers to his goodbye conference. Plantinga frequently wrote for the publication from 2007 to 2013.

CT profiled the Templeton Foundation and its $1 billion handoff in 2005 between founder Sir John Templeton, who died in 2008, and his son John “Jack” Templeton Jr., who died in 2015 days before Jean Vanier, founder of the disability ministry L’Arche, won the prize.

Miroslav Volf explained to CT why it’s significant that Rabbi Jonathan Sacks won the prize in 2016.

CT profiled 2002 prize winner John Polkinghorne, as well as interviewed him on how he saw the Bible as the laboratory notebook of the Holy Spirit. CT also interviewed 1994 prize winner Michael Novak on being a good capitalist.

CT noted when Campus Crusade founder Bill Bright won in 1996, when physicist Ian Barbour won in 1999, when physicist Freeman Dyson won in 2000, when biochemist Arthur Peacocke won in 2001, and when philosopher Charles Taylor won in 2007. CT also noted the death and influence of 1978 prize winner T. F. Torrance, a Reformed theologian.

Christian History highlighted the life and legacy of 1981 prize winner Dame Cicely Saunders.

Support Our Work

Subscribe to CT for less than $4.25/month