In this series

Peter Randolph, a slave in Prince George County, Virginia, until he was freed in 1847, described the secret prayer meetings he had attended as a slave. "Not being allowed to hold meetings on the plantation," he wrote, "the slaves assemble in the swamp, out of reach of the patrols. They have an understanding among themselves as to the time and place. … This is often done by the first one arriving breaking boughs from the trees and bending them in the direction of the selected spot.

"After arriving and greeting one another, men and women sat in groups together. Then there was "preaching … by the brethren, then praying and singing all around until they generally feel quite happy."

The speaker rises "and talks very slowly, until feeling the spirit, he grows excited, and in a short time there fall to the ground 20 or 30 men and women under its influence.

"The slave forgets all his sufferings," Randolph summed up, "except to remind others of the trials during the past week, exclaiming, 'Thank God, I shall not live here always!' "

It is a remarkable event not merely because of the risks incurred (200 lashes of the whip often awaited those caught at such a meeting) but because of the hurdles overcome merely to arrive at this moment. For decades all manner of people and circumstances conspired against African Americans even hearing the gospel, let alone responding to it in freedom and joy.

No time for religion

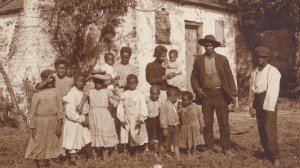

The plantation work regimen gave slaves little leisure time for religious instruction. Some masters required slaves to work even on Sunday. Even with the day off, many slaves needed to tend their own gardens, which supplemented their income and diet (others opted to socialize, to dance, or get drunk).

One of the largest obstacles was sheer prejudice. Many masters believed Africans were too "brutish" to comprehend the gospel; others doubted Africans had souls. Anglican missionary to South Carolina Francis Le Jau reported in 1709, "Many masters can't be persuaded that Negroes and Indians are otherwise than Beasts, and use them like such."

Such thinking was combated by men like Puritan Cotton Mather, who, in his tract The Negro Christianized, pleaded with owners to treat their "servants" as men, not brutes: "Thou shalt love thy neighbor as thy self. Man, thy Negro is thy neighbor."

Other masters believed conversion would make slaves "saucy," since they would begin to think of themselves equal to whites. According to John Bragg, a Virginia minister, slave owners agreed that conversion would result in the slaves "being and becoming worse slaves when Christians." Some even believed "A slave is ten times worse when a Christian than in his state of paganism."

There were legal complications as well. Many masters in colonial America believed if a slave was baptized that, "according to the laws of the British nation, and the canons of the church," he must be freed. Colonial legislatures sought to clear up this matter, and by 1706 at least six had passed acts denying that baptism altered the condition of a slave "as to his bondage or freedom." It wasn't just economics but a twinge of Christian conscience that prompted the legislation. As Virginia's law put it, it was passed so that masters, "freed from this doubt, may more carefully endeavor the propagation of Christianity."

But clergy were in short supply even for whites in the eighteenth-century South. In 1701 Virginia, for example, only half of the forty-some parishes containing 40,000 people were supplied with clergy. And regarding white settlers in Georgia, one missionary said, "They seem in general to have but very little more knowledge of a Savior than the aboriginal natives."

Finally, there were cultural obstacles. In 1701 the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts was formed, and one of its purposes was to seek the conversion of slaves in colonial America. As an arm of the Church of England, however, it was less than effective with the "target" population. Le Jau described his refined and rational method of teaching African Americans: "We begin and end our particular assembly with the collect. … I teach them the Creed, the Lord's Prayer, and the Commandments. I explain some portion of the catechism … "

With culture, prejudice, and injustice joining forces, few slaves were converted. As one missionary reported in 1779 about conditions in South Carolina: "The Negroes of that country, a few only excepted, are to this day as great strangers to Christianity and as much under the influence of pagan darkness, idolatry, and superstition as they were at their first arrival from Africa."

It would, it seemed, take a miracle to turn things around. And a miracle is just what America had already begun to experience.

Black awakening

In 1733, during a local revival instigated by his preaching, Jonathan Edwards noted, "There are several Negroes who … appear to have been truly born again in the late remarkable season." When the Great Awakening arrived in full—with shouts and groans and spiritual ecstasy—blacks began to swell the crowds coming to hear revival preachers. In Philadelphia, George Whitefield reported, "Nearly 50 Negroes came to give me thanks for what God had done to their souls." In the late 1740s, Presbyterian Samuel Davies said he ministered to seven congregations in Virginia in which "more than 1,000 Negroes" had participated in his services.

Presbyterian theology and Anglican liturgy, however, held little appeal to most blacks. Not until Methodists and Baptists arrived—with their emphasis on conversion as a spiritual experience—did black Christianity begin to take off.

John Thompson, who was born a Maryland slave in 1812, said he and his fellow slaves "could understand but little that was said" in the Episcopal service his owner required them to attend. But when "the Methodist religion was brought among us … it brought glad tidings to the poor bondsman." It spread from plantation to plantation, he said, and "there were few who did not experience religion."

Baptists and Methodists prized spiritual vitality more than education in clergy, so if a converted African American showed a gift for preaching, he was encouraged to preach, even to unconverted whites. Thus arose the earliest black preachers of repute, men with names like "Black Harry" Hosier, Josiah Bishop, "Old Captain," and "Uncle" Jack.

The Great Awakening, then, planted the seed of a more experiential type of Christianity that blossomed suddenly late in the eighteenth century. Black Methodism in the U. S. grew from 3,800 in 1786 to nearly 32,000 by 1809. Membership in black Baptist congregations increased as well, from 18,000 in 1793 to 40,000 in 1813.

Southern whites were not necessarily comfortable with this. Though a few masters argued that slaves "do better for their masters' profit than formerly, for they are taught to serve out of Christian love and duty," others kept their slaves distant from the Christian preaching. Francis Henderson, a fugitive slave, said his master had refused him permission to attend a Methodist church saying, "You shan't go to that church—they'll put the devil in you."

And Francis Asbury, the famous Methodist bishop, complained, "We are defrauded of great numbers by the pains that are taken to keep the blacks from us."

By 1820, one white Presbyterian minister, Charles C. Jones, could still moan, "But a minority of the Negroes, and that a small one, attended regularly the house of God, and … their religious instruction was extensively and most seriously neglected."

A slave conspiracy in 1822 and a revolt in 1831 didn't help matters. The conspiracy was led by Denmark Vesey who, as one co-conspirator confessed, "read in the Bible where God commanded that all [whites] should be cut off, both men, women, and children, and said it was no sin for us to do so, for the Lord commanded us to do it." The slave revolt, the bloodiest in U.S. history, in Southampton, Virginia, was led by Nat Turner, a prophet and preacher, who said he had been directed to act by God. After such incidents, masters were even more reluctant to let blacks gather alone for any reason.

Still, the southern conscience, pricked by northern abolitionist agitation, prompted increasingly more slave owners to take the Great Commission seriously. Slave owners wanted to prove that slaveholding could be a positive good for both owners and slaves.

In 1829, the South Carolina Methodist Conference appointed William Capers to superintend a special department for plantation missions—the first official and concerted effort of the sort. Four years later, Charles Jones began a ministry to evangelize slaves and to convince others to do likewise.

Jones, called "the apostle to the negro slaves" was, in fact, a slave owner. He came from a distinguished Georgia family and eventually owned three plantations and 129 slaves. A man with one compassionate eye and another fierce with purpose, Jones urged his southern brethren to "look to home" first. "The religious instruction of our servants is a duty," he wrote in 1834. "Any man with a conscience may be made to feel it. It can be discharged. It must be discharged … as speedily as possible." This would not only win the approval of God and their own consciences, he argued, but also the respect of the North.

After the major denominations—Methodist, Presbyterian, and Baptist—split over slavery, efforts to evangelize slaves accelerated. Southern whites were eager to show northerners that a gentle, Christian society—slave and free—could flourish in the South.

According to some southerners they succeeded: by 1845, one southern churchman crowed that the slave mission "is the crowning glory of our church."

Failure of white Christianity

The gospel presented to slaves by white owners, however, was only a partial gospel. The message of salvation by grace, the joy of faith, and the hope of heaven were all there, but many other teachings were missing.

House servants often sneered and laughed among themselves when summoned to family prayers because the master or mistress would read, "Servants obey your masters," but neglect passages that said, "Break every yoke and let the oppressed go free."

One white evangelist to slaves, John Dixon Long, admitted his frustration: "They hear ministers denouncing them for stealing the white man's grain, but as they never hear the white man denounced for holding them in bondage, pocketing their wages, or selling their wives and children to the brutal traders of the far South; they naturally suspect the Gospel to be a cheat and believe the preachers and slaveholder [are] in a conspiracy against them."

The institutional church, in both the North and South, had long before deserted the slaves—even the Methodists, who early on insisted that slave owners, upon their conversion, free their slaves. But by 1804, the General Conference agreed to let Methodist societies in the Carolinas, Georgia, and Tennessee allow their members to buy and sell slaves. And in 1808, the annual conference of the Methodist church authorized each conference to determine its own regulations about slaveholding.

After Denmark Vesey and his fellow conspirators (many of whom were Methodists) were arrested, southern clergy felt constrained by public opinion to affirm the racial status quo. Baptists and Episcopalians in Charleston denied any intention of interfering with slavery. By the early 1800s, the southern churches had completely folded on the issue.

In instance after instance recorded in countless slave narratives, the conversion of masters made matters worse for slaves. As ex-slave Mrs. Joseph Smith explained it, the non-religious owner simply gave slaves Sundays off and ignored them the entire day. But Christian owners, eager for the sanctification of their charges, could not let Sundays pass without due vigilance.

As Smith explained, "Now, everybody that has got common sense knows that Sunday is a day of rest. And if you do the least thing in the world they [the owners] don't like; they will mark it down against you, and Monday you have got to take a whipping."

Some didn't wait until Monday. One slave reported that his master served him Communion at church in the morning and whipped him in the afternoon for returning to the plantation a few minutes late. Susan Boggs recalled the day of her baptism: "The man that baptized me had a colored woman tied up in his yard to whip when he got home. … We had to sit and hear him preach, and [the woman's] mother was in church hearing him preach."

It is not difficult to see why Frederick Douglass called slaveholding piety "a cold and flinty-hearted thing, having neither principles of right action nor bowels of compassion."

Experiencing the real

It is amazing that under these circumstances any slaves found the Christian message convincing. And yet blacks clearly saw the difference—a difference white owners were utterly blind to—between the message of the Bible and the slaveholding culture in which it was taking root. When William Craft's supposedly Christian master sold his aged parents because they were no longer an economic asset, Craft said he felt "a thorough hatred, not for Christianity, but for slaveholding piety."

Slaves, when hearing the Christian message, were struck by something that transcended their culture. Many of them described how they were seized by the Spirit, struck dead (so to speak), and raised to a new life. Such conversions took place in the fields, in the woods, at camp meetings, in the slave quarters, or at services conducted by the blacks themselves.

John Jasper, a famous black preacher in Richmond, for example, was converted while at work as a stemmer in a tobacco factory. He remembered that when "de light broke; I was light as a feather; my feet was on de mount'n; salvation rol'd like a flood thru my soul, an' I felt as if I could knock off de fact'ry roof wid my shouts."

Josiah Henson said he was "transported with delicious joy" when he heard a sermon from the Book of Hebrews that said Christ tasted death "for every man." He exclaimed, "O the blessedness and sweetness of feeling that I was loved!"

Such experiences were so real that nothing masters did or said could shake their Christian confidence.

Of course, this experience of faith was not sustained by the "family prayers" led by the master or mistress, or the formal worship at which both blacks and whites gathered on Sundays. Such formats were heavily proscribed by the sensibilities and fear of white Christians.

In such settings, gifted blacks were sometimes allowed to preach. They were usually limited to assisting white preachers, which included the obligatory admonition at the end of the service for slaves to pay attention to the teachings of the white preacher. One ex-slave said, "We had some nigger preachers but they would say, 'Obey your mistress and master.' They didn't know nothing else to say."

Even when blacks met alone, though, preachers had to be circumspect. As one put it, "If a colored preacher or intelligent free Negro gains the ill-will of a malicious slave, all the latter has to do is to report that said preacher had attempted to persuade him to 'rise' or to run away; and the poor fellow's life may pay the forfeit."

Then, when alone with his black brothers and sisters, he would add, " … iffen they keeps praying, the Lord will set 'em free."

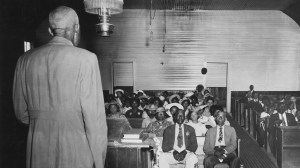

Invisible church

Yet it wasn't just the message that was chained by the circumstances, but the very style of worship blacks yearned to express. Sarah Fitzpatrick, an Alabama slave, noted, "White fo'ks have deir service in de mornin', an' niggers have deirs in de evenin', a'ter dey clean up, wash de dishes, an' look a'ter eve'thing. … Ya' see niggers lack [like] ta shout a whole lot, an' wid de white fo'ks al' round 'em, dey couldn't shout jes' lack dey want to."

Although some southern whites forbade blacks from meeting alone, this didn't stop slaves from taking risks to enjoy their own experience of the Spirit. Ex-slave Charlotte Martin, for example, said her oldest brother was whipped to death for secreting off to a worship service.

Lucretia Alexander explained that after enduring the white preacher's sermon ("Serve your masters. Don't steal your master's turkey. … Do whatsoever your master tells you do to"), her father would hold worship secretly in one of the slave quarters. "That would be when they would want a real meetin' with some real preachin'. … They used to sing their songs in a whisper and pray in a whisper."

To get a little distance between themselves and their masters, slaves would often meet in woods, gullies, ravines, and thickets, aptly called "hush harbors." Kalvin Woods recalled singing and praying with other slaves, huddled behind quilts and rags, hung "in the form of a little room" and wetted "to keep the sound of their voices from penetrating the air."

On one Louisiana plantation, slaves would steal off into the woods and "form a circle on their knees around the speaker, who would also be on his knees. He would bend forward and speak into or over a vessel of water to drown the sound. If anyone became animated and cried out, the others would quickly stop the noise by placing their hands over the offender's mouth."

Such secrecy was not required everywhere, and in many places and upon a variety of occasions—Sunday worship, prayer meetings, baptisms, and revivals—blacks worshiped alone and in full voice. As one ex-slave put it, referring to camp meetings: "Mostly we had white preachers, but when we had a black preacher, that was heaven."

Frederick Law Olmsted described one New Orleans service he attended in 1860. A man sitting next to him "soon began to respond aloud to the sentiments of the preacher, in such words as these: 'Oh yes!' and similar expressions could be heard from all parts of the house whenever the speaker's voice was unusually solemn, or his language and manner eloquent or excited."

Olmstead also noted "shouts, and groans, and terrific shrieks, and indescribable expressions of ecstasy—of pleasure or agony—and even stamping, jumping, and clapping hands were added."

He then focused on one worshiper: "The preacher was drawing his sermon to a close … when a small old woman … suddenly rose, and began dancing and clapping her hands; at first with slow measured movement, and then with increasing rapidity, at the same time beginning to shout 'Ha! Ha!' … her head thrown back and rolling from one side to the other. Gradually her shout became indistinct; she threw her arms wildly about instead of clapping her hands, fell back into the arms of her companions, then threw herself forward and embraced those before her, then tossed herself from side to side, gasping and finally sunk to the floor, where she remained … kicking, as if acting a death struggle."

Perhaps it was indeed a death struggle—with an oppressive culture that sought to wring life, physical and spiritual, out of her. But if so, it was one that moved toward resurrection. One ex-slave preacher talked about the effect of such services: "The old meeting house caught on fire. The spirit was there. Every heart was beating in unison as we turned our minds to God to tell him our sorrows here below. God saw our need and came to us."

Many black preachers didn't know a letter of the Bible or how to spell the name of Christ. "But when they opened their mouths," said one ex-slave, "they were filled, and the plan of salvation was explained in a way that all could receive it." Sometimes the exhorter merely related his conversion experience, or how God had comforted him in times of distress. When the preacher was exhausted, he said, the faces of the listeners "showed that their souls had been refreshed and that it had been 'good for them to be there.' "

Confident faith

By the time the guns of Fort Sumter pounded forth in 1860, the number of black Christians below the Mason-Dixon line had grown to an astounding half-million, not counting the thousands who participated secret slave worship. The numbers were uneven across the South: black Christians constituted 20 percent of the black population in South Carolina, but only about 10 percent in Virginia. In some cities, there were black congregations that numbered in the thousands. All in all, this was about double the number of black Christians from the early 1800s, and multiples more than in the early 1700s.

That blacks accepted the Christian gospel is remarkable in itself, considering the stumbling blocks thrown in their way. Certainly some of the success must be credited to white missionaries—both slave owners and abolitionists—who insisted that slaves hear at least the rudiments of the Christian message.

But the Christianity that finally took hold of black souls, that grew and blossomed in its own distinct way, and that comforted and gave hope to a sorely oppressed people, was a different thing altogether than what whites had imagined. It was in some sense created and nurtured by blacks themselves, who refused to let whites frame their faith.

Instead they discovered for themselves the biblical message, as historian Arnold Toynbee put it, "that Jesus was a prophet who came into the world not to confirm the mighty in their seats but to exalt the humble and the meek."

This not only gave blacks hope but a confidence whites recognized and feared. Francis Henderson described her conversion this way: "I had recently joined the Methodist Church, and from the sermons I heard, I felt that God had made all men free and equal, and that I ought not be a slave—but even then, that I ought not to be abused. From this time I was not punished. I think my master became afraid of me."

Black boldness was due in part to their belief in God's special concern for the poor. As ex-slave Jacob Stoyer put it, "God would somehow do more for the oppressed Negroes than he would ordinarily for any other people."

But blacks were also bolstered by their trust in a coming judgment at which slaveholders would receive recompense. Moses Grandy remembered how during violent thunderstorms whites hid between their feather beds, whereas slaves went outside and, lifting up their hands, thanked God that judgment day was coming at last."

It was, in the end, a confidence in a God who would set things right, either in this age or in the age to come. At age 90, Jane Simpson recalled, "I used to hear old slaves pray and ask God when would de bottom rail be de top rail, and I wondered what on earth, dey talkin' about. Dey was talkin' about when dey goin' to get from under bondage. 'Course I know now."

Mark Galli is the editor of Christianity Today. This article orginally appeared in Christian History. To prepare this article, Mr. Galli relied upon Albert J. Raboteau's Slave Religion: The Invisible Institution (Oxford, 1978) and Milton Sernett's Black Religion and American Evangelicalism (Scarecrow, 1975).