They can arguably be termed the most authentic "protestants" in modern church history. Only a handful of black Baptist churches were allowed to exist before the Civil War, but they were known for their arguments for the "brotherhood of man" and against the institution of slavery. From this sprinkling of churches came a thriving denomination that a mere century later produced the Revs. Adam Clayton Powell, Jr., Martin Luther King, Jr., and Jesse Jackson—products of the black Baptist tradition of activism.

In the 1700s, white Baptists rarely evangelized slaves, although records show occasional examples of black members. First Baptist Church of Providence, Rhode Island, notes that 19 African Americans held membership as early as 1772.

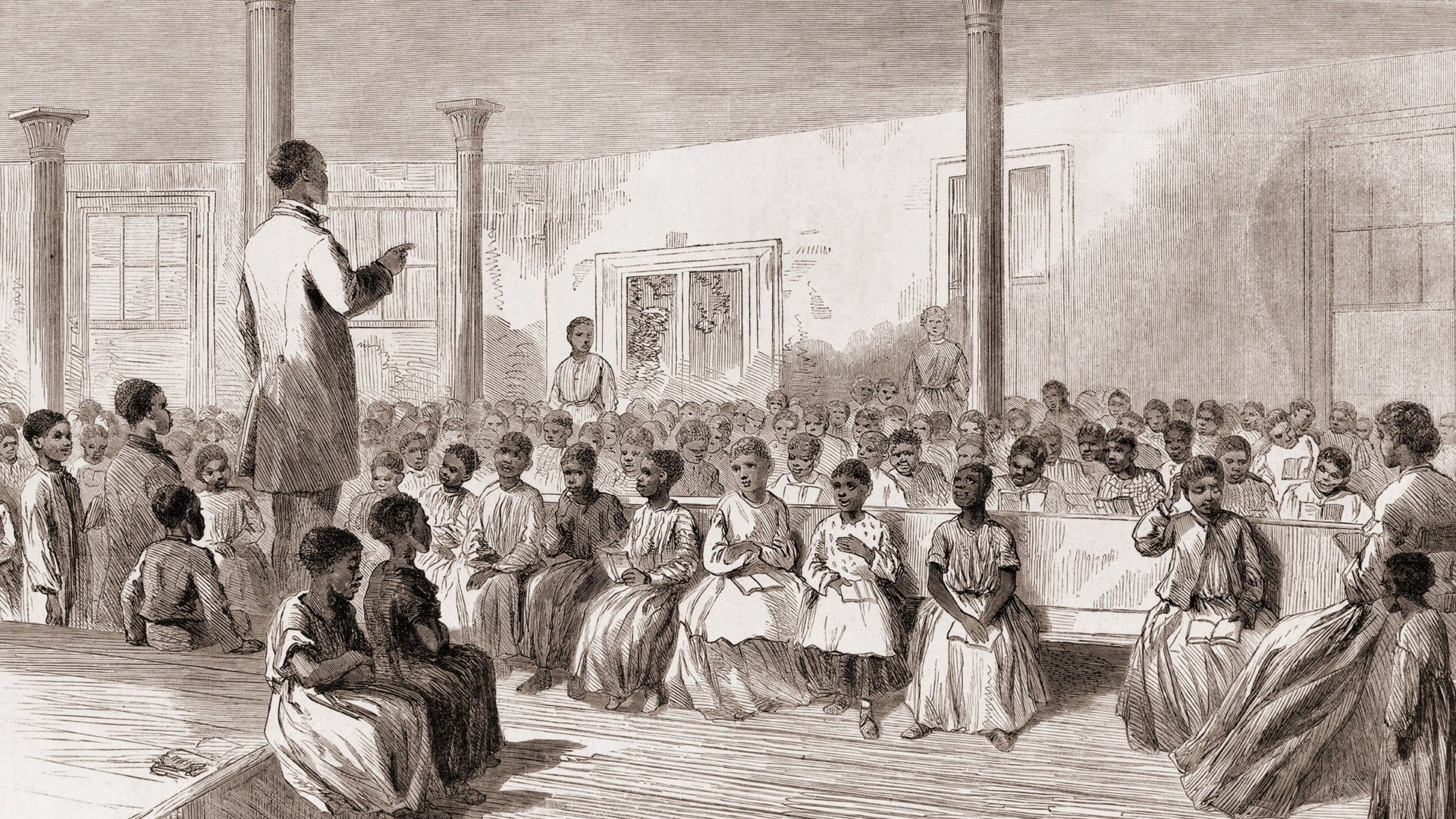

The first black Baptist institution, however, came from the South when slave owners permitted the ministry of slave preachers. The first of these was Harry Cowan of North Carolina, a servant of Thomas L. Cowan, who gave his slave "privilege papers" so he could preach anywhere on his four plantations.

George Liele, who preached powerfully on plantations in South Carolina and Georgia, expanded this institution by helping to establish the earliest independent black Baptist churches (see "The Expatriate Option," p. 32). But Liele and his companions were the exception. Generally, black slaves were not allowed to have their own churches, pastors, or preachers.

This oppression intensified after Nat Turner (himself a Baptist preacher) led his 1831 rebellion (see "God's Avenging Scourge," p. 28). Within a year, Virginia legislators prohibited any black, free or slave, from conducting religious meetings. Other southern states followed suit.

In the North, black Baptists faced fewer challenges, and they organized churches in Boston in 1805, New York in 1808, and Philadelphia in 1809. The most progressive group, however, came from Ohio, beginning the first missionary movement in the area and organizing (in 1834) the first association of black Baptist churches, the Providence Baptist Association.

Only a few years later, black Baptists were trying to unify across state lines, beginning in 1840 with the American Baptist Missionary Convention. Such cooperation was driven in large part by a desire to evangelize Africa.

"They were quite motivated to go back to their own extended families in Africa," says Leroy Fitts, author of A History of Black Baptists, "but it was very slow progress."

Many cooperative missions followed until the dream of national unity was realized in the formation of the National Baptist Convention in 1895, and within a few years, it would exceed 2 million members, producing black leaders like Booker T. Washington and key black institutions like Wayland Seminary in Washington, D.C. Even though suffering a split in 1915, it is today the largest African-American denomination in the world.

A freelance writer based in Gaithersburg, Maryland, Carolyn McCulley has written for publications ranging from Christianity Today to the Washington Post.

Copyright © 1999 by the author or Christianity Today/Christian History Magazine. Click here for reprint information on Christian History.