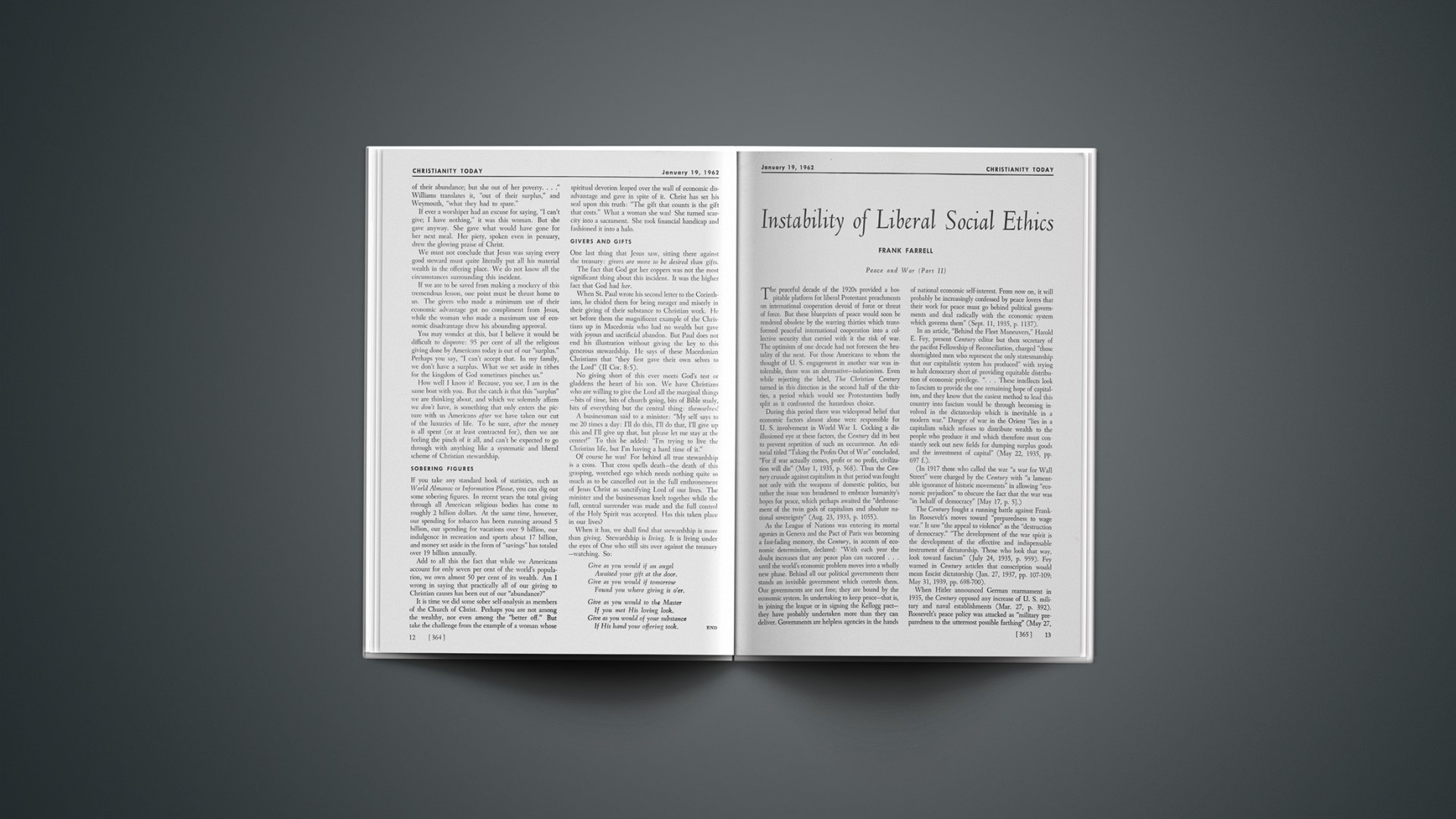

Peace and War (Part II)

The peaceful decade of the 1920s provided a hospitable platform for liberal Protestant preachments on international cooperation devoid of force or threat of force. But these blueprints of peace would soon be rendered obsolete by the warring thirties which transformed peaceful international cooperation into a collective security that carried with it the risk of war. The optimism of one decade had not foreseen the brutality of the next. For those Americans to whom the thought of U. S. engagement in another war was intolerable, there was an alternative—isolationism. Even while rejecting the label, The Christian Century turned in this direction in the second half of the thirties, a period which would see Protestantism badly split as it confronted the hazardous choice.

During this period there was widespread belief that economic factors almost alone were responsible for U. S. involvement in World War I. Cocking a disillusioned eye at these factors, the Century did its best to prevent repetition of such an occurrence. An editorial titled “Taking the Profits Out of War” concluded, “For if war actually comes, profit or no profit, civilization will die” (May 1, 1935, p. 568). Thus the Century crusade against capitalism in that period was fought not only with the weapons of domestic politics, but rather the issue was broadened to embrace humanity’s hopes for peace, which perhaps awaited the “dethronement of the twin gods of capitalism and absolute national sovereignty” (Aug. 23, 1933, p. 1055).

As the League of Nations was entering its mortal agonies in Geneva and the Pact of Paris was becoming a fast-fading memory, the Century, in accents of economic determinism, declared: “With each year the doubt increases that any peace plan can succeed … until the world’s economic problem moves into a wholly new phase. Behind all our political governments there stands an invisible government which controls them. Our governments are not free; they are bound by the economic system. In undertaking to keep peace—that is, in joining the league or in signing the Kellogg pact—they have probably undertaken more than they can deliver. Governments are helpless agencies in the hands of national economic self-interest. From now on, it will probably be increasingly confessed by peace lovers that their work for peace must go behind political governments and deal radically with the economic system which governs them” (Sept. 11, 1935, p. 1137).

In an article, “Behind the Fleet Maneuvers,” Harold E. Fey, present Century editor but then secretary of the pacifist Fellowship of Reconciliation, charged “those shortsighted men who represent the only statesmanship that our capitalistic system has produced” with trying to halt democrary short of providing equitable distribution of economic privilege. “… These intellects look to fascism to provide the one remaining hope of capitalism, and they know that the easiest method to lead this country into fascism would be through becoming involved in the dictatorship which is inevitable in a modern war.” Danger of war in the Orient “lies in a capitalism which refuses to distribute wealth to the people who produce it and which therefore must constantly seek out new fields for dumping surplus goods and the investment of capital” (May 22, 1935, pp. 697 f.).

(In 1917 those who called the war “a war for Wall Street” were charged by the Century with “a lamentable ignorance of historic movements” in allowing “economic prejudices” to obscure the fact that the war was “in behalf of democracy” [May 17, p. 5].)

The Century fought a running battle against Franklin Roosevelt’s moves toward “preparedness to wage war.” It saw “the appeal to violence” as the “destruction of democracy.” “The development of the war spirit is the development of the effective and indispensable instrument of dictatorship. Those who look that way, look toward fascism” (July 24, 1935, p. 959). Fey warned in Century articles that conscription would mean fascist dictatorship (Jan. 27, 1937, pp. 107–109; May 31, 1939, pp. 698–700).

When Hider announced German rearmament in 1935, the Century opposed any increase of U. S. military and naval establishments (Mar. 27, p. 392). Roosevelt’s peace policy was attacked as “military preparedness to the uttermost possible farthing” (May 27, 1936 p. 757), and the Century therefore desired replacement of “the present weak neutrality laws with legislation of an inclusive and mandatory character” (Jan. 6, 1937, p. 8). As war drew near, the “President’s demand for a supernavy” was opposed (Mar. 9, 1938, pp. 294–296; May 4, 1938, pp. 550 f.).

The Century earlier had called for a U.S. guarantee of economic (as well as military) neutrality with an embargo on every form of help to make war, applying to all nations, Britain included. If such a peace plan were followed, “… we believe that the danger of a new world war would be almost done away” (Mar. 28, 1934, p. 412). By 1939 desire for such legislation remained—alongside pessimism as to the possibility of attaining it (May 17, p. 632).

In 1937 the Century acknowledged that the Kellogg Pact had broken down. It also admitted that American isolation was a chief factor in preventing the collective system (embodied in the League) from functioning, but after all, the League was seen as a means of perpetuating the Versailles treaty and of developing a balance of power, both undesirable to the Century (Sept. 15, 1937, pp. 1127–29).

Memory Of The First World War

Helping to push the Century toward isolationism was the memory of World War I and the “element of shame” in the churches’ support of that war (Jan. 20, 1937, pp. 72–74). Morrison pointed to the heavy financial burdens of the magazine which took much of his time until 1919 when three men gave him adequate financial support. “I have no illusion that The Christian Century would have taken a radically different position had the financial release come earlier. The idea that war was a religious issue, a test of religious reality, in the way we now conceive it, was too vague to do more than haunt my conscience ineffectually.” As for his 1937 position on war, he noted the Century had never taken the pledge of absolute pacifism but declared that the philosophical differences were “academic.” He took satisfaction in its pioneering contribution to the “volume of Christian conviction against war” developed since World War I (Mar. 31, 1937, pp. 409–411).

On the eve of war, the churches were told they could not in good conscience leave Christian conscientious objectors in doubt as to church support since their decisions were made on the basis of the churches’ teaching on “the sinful nature of war” (June 7, 1939, p. 729). The churches were also repeatedly urged to withdraw from the military chaplaincy program (Dec. 21, 1938, pp. 567–569; Jan. 16, 1935, pp. 70–72).

However, Fey’s advocacy of the proposed Ludlow amendment to the Constitution, making declaration of war dependent upon a national referendum, was opposed by the Century as increasing “the danger of resort in crisis to a fascist dictatorship” (Jan. 5, 1938, p. 8; cf. Dec. 29, 1937, pp. 1617 f.).

Pacifists often seem impelled by their own interests to draw a nicer picture of the enemy than warranted by the facts. Aggressions tend to be rationalized. Conversely, the weak points of their own society tend to be exaggerated. In an article, “Cancel the Naval Maneuvers!” Fey declared: “… the recent attitude of our government toward Japan has been aloof, hostile and is now verging on the provocative.” “What is needed now is … organization to make the provocative actions of our government unpopular … and to prepare a continuing method of opposition to war should war occur” (Mar. 6, 1935, pp. 298, 300). R. M. Miller cites as pacifist intolerance the Century’s terming “Albert Einstein’s defection from absolute pacifism (after his experiences in Nazi Germany) an unworthy deed indicating the scientist was not made of stern stuff” (American Protestantism and Social Issues, 1919–1939, p. 339).

The Century was determined not to be provoked by aggression into support of war. Though detesting the Franco revolt in Spain, democracy in Spain was declared destroyed whatever the outcome of the conflict. Thus the Century opposed liberals who advocated sending American volunteers to fight for the Spanish government: “America has already been betrayed into one European war over this faked issue of saving democracy” (Jan. 27, 1937, pp. 104–106).

The May 19 issue of 1937 contained an editorial, “Japan Turns Toward Peace,” which noted some soft Tokyo words toward China and concluded the prospect for peace in eastern Asia to be the brightest in a generation, with Japanese imperialist thought beginning “to pass into eclipse” (pp. 640–642). But in July Japan launched a full scale attack upon China. The Century called for application of the neutrality law, declaring U. S. involvement “in the tragic events by which Asiatic peoples will work out their fates” would be folly (Aug. 11, 1937, pp. 989–991).

The journal favored invoking the neutrality law not only in Asia but also against Italy, Germany, Russia, and the “ostensible combatants in Spain” (Aug. 11, 1937, p. 991). It denounced Anthony Eden’s toughness toward dictators and expressed hope that Premier Chamberlain’s pre-Munich concessions to them would bring peace (Mar. 2, 1938, pp. 262 f.). Austria’s annexation was taken lightly (Mar. 23, 1938, p. 358).

The Century noted the recession of pacifist sentiment in the American churches in reaction to Hitler and his Munich gains. Racial arrogance made clear the “unregenerate and brutish instincts of human nature despite Christianity’s long acceptance in Western civilization,” and was a further challenge to pacifist faith (Dec. 28, 1938, p. 1600).

On the Munich settlement, the Century vacillated from week to week between condemning Germany on one hand and Britain and France on the other. Munich, it was said, was possibly no more immoral than Versailles (Sept. 28, 1938, pp. 1150–1152; Oct. 12, pp. 1224–1226; Nov. 30, pp. 1456–1458). There was no ideological crisis—“Munich Europe” had simply reverted to the old game of power politics (Feb. 15, 1939, pp. 206 f.).

Among those who followed this line of thought, the bogy of Versailles seemed to blot from memory the harsh treaty of Brest-Litovsk dictated by Germany to Russia in 1918 (see D. B. Meyer, The Protestant Search for Political Realism, 1919–1941, pp. 378–380).

From Munich to Pearl Harbor, the Century was determinedly and vociferously isolationist. Coming of war in Europe did not change this stand save to intensify it. American morality, it was urged, demanded it.

The month before the war, President Roosevelt was excoriated for hoping to “extricate the nation from its economic difficulties” by making munitions available to European nations in time of war. Speaking in accents of the America Firsters, the editorial went on: “Why should the United States enter another general European war?… No nation could win a major war today, either in Europe or Asia, and have enough strength left to contemplate invasion of the Western hemisphere for a generation” (Aug. 2, 1939, pp. 942 f.). But the old pacifist internationalism expressed itself in a call by C. C. Morrison and others for a world economic conference to turn aside the threat of war. European churchmen replied that the crisis had moved beyond the economic phase, but at American insistence, leaders of the World Council of Churches finally suggested a small unofficial meeting of churchmen. Thirty-four persons gathered and produced a statement. By the time of its publication in the Century, war had already been declared (Meyer, op. cit., pp. 372 f.).

With the return of war, the Century prophesied the possible end of civilization, applauded Roosevelt’s, pledge to attempt preservation of America’s peace, urged maintenance of the arms embargo, and expressed lack of concern for Poland’s fate because of that country’s “record of persecuting its minorities” (Sept. 13, 1939, pp. 1094 f.; Sept. 20, pp. 1126–1129).

In “Not America’s War” the Century set its goal for the next two years in stressing the necessity of guarding the American mind “at the point of its sentimental prompting” to go to the aid of the Allies.

“When the war is stripped of its pretensions it stands forth in its naked motivation as a war of empires. It is not England’s war. It is the British empire’s war. This fact, seen steadily, should be enough to deflate the appeal to America to come in and help save democracy. For democracy and imperialism are incompatible.…

“There is not room in the world for two imperialisms such as Britain is and Germany wants to be … The United Kingdom, consisting of England, Scotland, Wales and Ulster, would be, apart from the empire, in no more danger from Germany or any European power than is Norway or Sweden or Denmark.… It is the existence of the British empire which, together with imperial France, has produced Nazi Germany.… Great Britain must be made to know that America will not come to the defense of the British empire.…” (Nov. 22, 1939, pp. 1431–1433).

This sort of interpretation roused the ire of many Protestant leaders. Names like Niebuhr, Oxnam, Van Dusen, Dulles, Sherrill, Mott, and Mackay appeared under a declaration that “an interpretation of the present conflicts as merely a clash of rival imperialisms can spring only from ignorance or moral confusion. The basic distinction between civilizations in which justice and freedom are still realities and those in which they have been displaced by ruthless tyranny cannot be ignored” (Jan. 31, 1940, pp. 152 f.).

French Disaster And Yet Hope

In commenting on the fall of France, the Century looked to Hitler with a little hope. It reminded its readers that Hitler had “proclaimed this war as a crusade on plutocratic capitalism” and that his national socialism had brought about a social revolution which had driven capitalism out of control of Germany. “We Americans have minimized the reality and importance of this revolution because we have been revolted by its hideous brutalities and disgusted by the personalities of its leaders.… Can Hitler give the rest of the world a system of interrelationships better than the tradestrangling and man-exploiting system of empire capitalism? We have small hope that he can, but hope must not be given up entirely until it is known what he intends to do with this victory” (June 26, 1940, p. 815).

An attempted probing of Europe’s future sought to reassure anxious Americans that France’s fate would not really be so bad after all:

“In a united Europe governed from the German center, with a unified planned economy covering the continent, France will be able to find compensations in terms of human values. A France which has thrown off the artificial structure of empire and of capitalistic dominion in industry, together with the intolerable burden of the vast military establishment which goes with them, may experience a new emancipation, a genuine and creative revival of economic freedom. Such a France may be the first great modern society to pass through the gate of disillusionment concerning those values clustering about the mythical concept of the “economic man” which have hypnotized and perverted Western civilization for centuries” (Sept. 25, 1940, p. 1166).

France was expected to emerge from subjection before too long. “A France that is a product of schools which have been swept clean of secularism will be at least a France with a faith—and a faith which is incompatible with the faith of nazis” (ibid., p. 1167). Meyer graphically describes the Century ordeal:

“The ‘at least’ was a pressure point, betraying the terrible costs Morrison was having to pay: the new schools he was describing were the schools into which Roman Catholicism had been returned. The political structure he thought might follow Hitler was an Italian-French-Spanish bloc, a “Latin Catholic totalitarianism.” In the man who had fixed sharply upon the ‘short-run’ issues in 1928 [A1 Smith’s presidential campaign], … who had protested the Taylor mission to the Vatican, it was apparent that for him to down such bitter potion—the thirst for neutrality burned the soul” (op. cit., p. 381).

Roosevelt Toward Fascism

On the home front, the Century was fighting against conscription and a third term for Roosevelt: “If to the cohesive strength of the selfish interests which constitute the party in power is now added conscription, the President’s power, having broken the two-term limitation, will be essentially the same as that of any European dictator” (Aug. 28, 1940, p. 1047). “The party in power, unable to unify the national life at the level of its economic well-being, now turns to the war as a unifying substitute.” The one-party system was seen as the essence of fascism. “[Mr. Roosevelt] is the Führer of this inchoate fascism” (July 31, 1940, pp. 942 f.). Conscription was seen as increasing the danger of war rather than contributing to America’s defense (Sept. 25, 1940, pp. 1168–1170).

Meyer points out that Morrison’s peace apology “colored with bitterness” as he both suffered the excruciation of his own “inner rationalizations” and became the object of “the most withering of the fire of the interventionists” (op. cit., pp. 381 f.). In answer to the question, “What can America do for peace?” the Century proposed the President send a delegation of American statesmen to Europe’s neutral capitals to convene a peace conference to sit until war’s end and plan a new Europe (May 15, 1940, pp. 630–632). In a Century article, “Irresponsible Idealism,” Union Seminary’s Henry P. Van Dusen flayed the Century for grossly misleading Christians to think a peace conference would have the slightest chance of success. He charged: “resolute unwillingness” to face known facts, “falsification of issues,” unforgivable escapism, and “betrayal of truth” (July 24, 1940, pp. 924 f.). The Century in turn described Van Dusen’s mind as one of “the war’s intellectual casualties” (ibid., p. 919).

Reinhold Niebuhr saw in the conference proposal “a completely perverse and inept foreign policy,” a search for a “simple way out” (May 29, 1940, pp. 706 f.). He charged forgetfulness of: Germany’s “pagan religion of tribal self-glorification,” its intention to “root out the Christian religion,” its defiance of universal standards of justice, its “maniacal fury” toward the Jews, its declared intention of enslaving the other races of Europe “to the ‘master’ race.” “If anyone believes that the peace of such a tyranny is morally more tolerable than war I can only admire and pity the resolute dogmatism which makes such convictions possible.” Niebuhr felt uneasy in the security he possessed while others were dying for principles in which he believed. The question of American intervention was “not primarily one of the morals but of strategy in the sense that I believe we ought to do whatever has to be done to prevent the triumph of this intolerable tyranny.” The Century’s type of neutralism was characterized as “pitiless perfectionism, which has informed a large part of liberal Protestantism in America” and which was wrong not only on the war issue but “wrong about the whole nature of historical reality,” for it failed to see that justice had always been established through tension between various forces and interests in society. Niebuhr allowed a place for a thoroughgoing pacifism resigned to martyrdom and political irresponsibility, “but we have precious little of it in America because most of our pacifism springs from an unholy compound of gospel perfectionism and bourgeois utopianism, the latter having had its rise in eighteenth century rationalism.” This “sentimentalized Christianity” “is always fashioning political alternatives to the tragic business of resisting tyranny,” but “no matter how they twist and turn, the protagonists of a political, rather than a religious, pacifism end with the acceptance and justification of, and connivance with, tyranny” (Dec. 18, 1940, pp. 1578–1580).

But still, the Ministers No War Committee of 1941 embraced far more names of eminent liberal Protestant clergymen than were found on the letterheads of any interventionist organization (Meyer, op. cit., p. 374). Responding to a Niebuhr criticism of pacifists, the Century described it as an illustration of an “evil spirit,” threatening the unity of the Church (July 2, 1941, pp. 853 f.). Niebuhr notwithstanding, the Century, though apprehensive at the prospect of a Hitler victory, also voiced “grave misgivings” as to the effect of a British victory (Jan. 8, 1941, p. 49) and declared that if Britain won, the British empire would “be extended to include the continent of Europe” (Feb. 5, 1941, p. 175). There was room for doubt, it was affirmed, that U. S. interests would be better served by British monopoly of the seas than by German (Dec. 12, 1941, p. 1537—to press before Pearl Harbor). Even though a Nazi victory would mean virtual slavery for Europeans not of the “master race,” on the positive side it would: probably lift the living standard in some regions; “establish socialism of a sort, at least to the extent of forcing a transfer of power from the capitalist classes”; and, additionally, “break the power of the international bankers” (Feb. 19, 1941, pp. 248 f.).

The Century actually did not wish victory for either side but kept pronouncing stalemate at various stages of the war and repeatedly demanded a negotiated peace, the treaty to provide for codification of international law by a world league. The cornerstone of such a juridical structure was to be the principle of outlawry of war. Believing that a “victor’s peace” could not even approximate justice, the Century called upon “the Christian forces of the world” to “rally their strength” for the achievement of a “peace without victory” (Mar. 12, 1941, pp. 353 f.).

When Congress passed the Lend-Lease bill, the Century saw the American form of government becoming one “not of men, but of a man,” hence taking a “long stride” toward Nazism (Mar. 19, 1941, p. 385). It had censured Roosevelt’s “arsenal of democracy” speech as “a trumpet call to war” (Jan. 1, 1941, pp. 47–49), but with Hitler’s attack on the Soviet Union, the Century advocated aiding the Soviets and China as well as Britain (July 2, 1941, p. 856).

Yet in the last issue before word of Pearl Harbor, the Century maintained: “Every national interest and every moral obligation to civilization dictates that this country shall keep out of the insanity of a war which is in no sense America’s war” (Dec. 12, 1941, p. 1538).

It is hardly necessary to say that Charles Clayton Morrison and many of the host of clerics who stood with him worked strenuously for what they sincerely believed to be the best for church, country and world.

But historian Miller cites the verdict of many historians from present perspective:

“… clerical pacifism debilitated the moral conscience of America and gave encouragement to the dictators. By insisting upon peace at any price, ministers blinded themselves to the enormity of the crimes of the dictators, risked the destruction of Western Europe, and cut their nation off from the democracies. Many churchmen overestimated the economic motivations for war, underestimated the demoniac element in man, minimized the necessity of coercion in international relations, and placed the pleasures of peace over the demands of justice” (op. cit., p. 344).

The judgment has obvious theological implications as to the optimistic liberal doctrine of man.