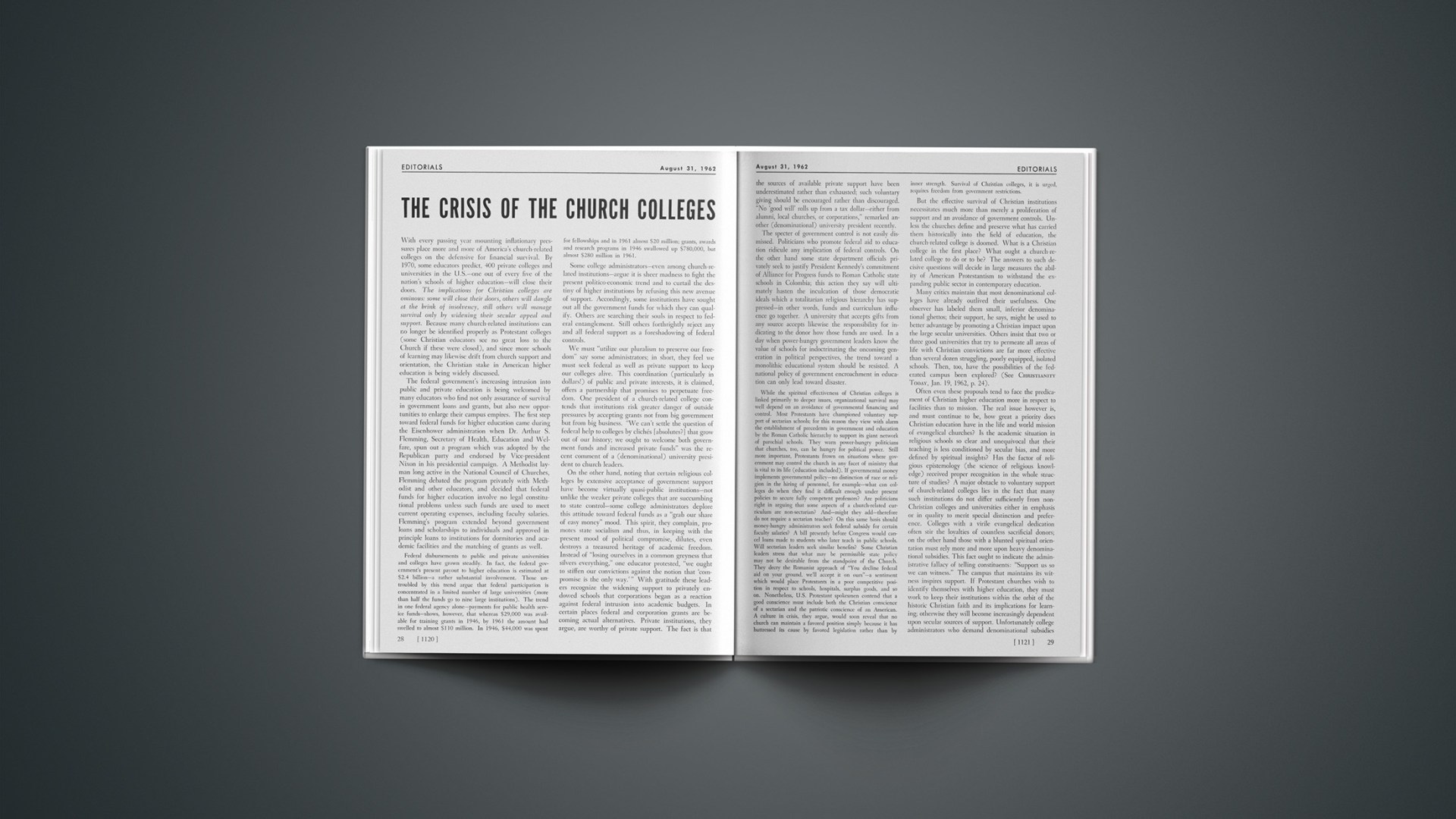

With every passing year mounting inflationary pressures place more and more of America’s church-related colleges on the defensive for financial survival. By 1970, some educators predict, 400 private colleges and universities in the U.S.—one out of every five of the nation’s schools of higher education—will close their doors. The implications for Christian colleges are ominous: some will close their doors, others will dangle at the brink of insolvency, still others will manage survival only by widening their secular appeal and support. Because many church-related institutions can no longer be identified properly as Protestant colleges (some Christian educators see no great loss to the Church if these were closed), and since more schools of learning may likewise drift from church support and orientation, the Christian stake in American higher education is being widely discussed.

The federal government’s increasing intrusion into public and private education is being welcomed by many educators who find not only assurance of survival in government loans and grants, but also new opportunities to enlarge their campus empires. The first step toward federal funds for higher education came during the Eisenhower administration when Dr. Arthur S. Flemming, Secretary of Health, Education and Welfare, spun out a program which was adopted by the Republican party and endorsed by Vice-president Nixon in his presidential campaign. A Methodist layman long active in the National Council of Churches, Flemming debated the program privately with Methodist and other educators, and decided that federal funds for higher education involve no legal constitutional problems unless such funds are used to meet current operating expenses, including faculty salaries. Flemming’s program extended beyond government loans and scholarships to individuals and approved in principle loans to institutions for dormitories and academic facilities and the matching of grants as well.

Federal disbursements to public and private universities and colleges have grown steadily. In fact, the federal government’s present payout to higher education is estimated at $2.4 billion—a rather substantial involvement. Those untroubled by this trend argue that federal participation is concentrated in a limited number of large universities (more than half the funds go to nine large institutions). The trend in one federal agency alone—payments for public health service funds—shows, however, that whereas $29,000 was available for training grants in 1946, by 1961 the amount had swelled to almost $110 million. In 1946, $44,000 was spent for fellowships and in 1961 almost $20 million; grants, awards and research programs in 1946 swallowed up $780,000, but almost $280 million in 1961.

Some college administrators—even among church-related institutions—argue it is sheer madness to fight the present politico-economic trend and to curtail the destiny of higher institutions by refusing this new avenue of support. Accordingly, some institutions have sought out all the government funds for which they can qualify. Others are searching their souls in respect to federal entanglement. Still others forthrightly reject any and all federal support as a foreshadowing of federal controls.

We must “utilize our pluralism to preserve our freedom” say some administrators; in short, they feel we must seek federal as well as private support to keep our colleges alive. This coordination (particularly in dollars!) of public and private interests, it is claimed, offers a partnership that promises to perpetuate freedom. One president of a church-related college contends that institutions risk greater danger of outside pressures by accepting grants not from big government but from big business. “We can’t settle the question of federal help to colleges by clichés [absolutes?] that grow out of our history; we ought to welcome both government funds and increased private funds” was the recent comment of a (denominational) university president to church leaders.

On the other hand, noting that certain religious colleges by extensive acceptance of government support have become virtually quasi-public institutions—not unlike the weaker private colleges that are succumbing to state control—some college administrators deplore this attitude toward federal funds as a “grab our share of easy money” mood. This spirit, they complain, promotes state socialism and thus, in keeping with the present mood of political compromise, dilutes, even destroys a treasured heritage of academic freedom. Instead of “losing ourselves in a common greyness that silvers everything,” one educator protested, “we ought to stiffen our convictions against the notion that ‘compromise is the only way.’ ” With gratitude these leaders recognize the widening support to privately endowed schools that corporations began as a reaction against federal intrusion into academic budgets. In certain places federal and corporation grants are becoming actual alternatives. Private institutions, they argue, are worthy of private support. The fact is that the sources of available private support have been underestimated rather than exhausted; such voluntary giving should be encouraged rather than discouraged. “No ‘good will’ rolls up from a tax dollar—either from alumni, local churches, or corporations,” remarked another (denominational) university president recently.

The specter of government control is not easily dismissed. Politicians who promote federal aid to education ridicule any implication of federal controls. On the other hand some state department officials privately seek to justify President Kennedy’s commitment of Alliance for Progress funds to Roman Catholic state schools in Colombia; this action they say will ultimately hasten the inculcation of those democratic ideals which a totalitarian religious hierarchy has suppressed—in other words, funds and curriculum influence go together. A university that accepts gifts from any source accepts likewise the responsibility for indicating to the donor how those funds are used. In a day when power-hungry government leaders know the value of schools for indoctrinating the oncoming generation in political perspectives, the trend toward a monolithic educational system should be resisted. A national policy of government encroachment in education can only lead toward disaster.

While the spiritual effectiveness of Christian colleges is linked primarily to deeper issues, organizational survival may well depend on an avoidance of governmental financing and control. Most Protestants have championed voluntary support of sectarian schools; for this reason they view with alarm the establishment of precedents in government and education by the Roman Catholic hierarchy to support its giant network of parochial schools. They warn power-hungry politicians that churches, too, can be hungry for political power. Still more important, Protestants frown on situations where government may control the church in any facet of ministry that is vital to its life (education included). If governmental money implements governmental policy—no distinction of race or religion in the hiring of personnel, for example—what can colleges do when they find it difficult enough under present policies to secure fully competent professors? Are politicians right in arguing that some aspects of a church-related curriculum are non-sectarian? And—might they add—therefore do not require a sectarian teacher? On this same basis should money-hungry administrators seek federal subsidy for certain faculty salaries? A bill presently before Congress would cancel loans made to students who later teach in public schools. Will sectarian leaders seek similar benefits? Some Christian leaders stress that what may be permissible state policy may not be desirable from the standpoint of the Church. They decry the Romanist approach of “You decline federal aid on your ground, we’ll accept it on ours”—a sentiment which would place Protestants in a poor competitive position in respect to schools, hospitals, surplus goods, and so on. Nonetheless, U.S. Protestant spokesmen contend that a good conscience must include both the Christian conscience of a sectarian and the patriotic conscience of an American. A culture in crisis, they argue, would soon reveal that no church can maintain a favored position simply because it has buttressed its cause by favored legislation rather than by inner strength. Survival of Christian colleges, it is urged, requires freedom from government restrictions.

But the effective survival of Christian institutions necessitates much more than merely a proliferation of support and an avoidance of government controls. Unless the churches define and preserve what has carried them historically into the field of education, the church-related college is doomed. What is a Christian college in the first place? What ought a church-related college to do or to be? The answers to such decisive questions will decide in large measures the ability of American Protestantism to withstand the expanding public sector in contemporary education.

Many critics maintain that most denominational colleges have already outlived their usefulness. One observer has labeled them small, inferior denominational ghettos; their support, he says, might be used to better advantage by promoting a Christian impact upon the large secular universities. Others insist that two or three good universities that try to permeate all areas of life with Christian convictions are far more effective than several dozen struggling, poorly equipped, isolated schools. Then, too, have the possibilities of the federated campus been explored? (See CHRISTIANITY TODAY, Jan. 19, 1962, p. 24).

Often even these proposals tend to face the predicament of Christian higher education more in respect to facilities than to mission. The real issue however is, and must continue to be, how great a priority does Christian education have in the life and world mission of evangelical churches? Is the academic situation in religious schools so clear and unequivocal that their teaching is less conditioned by secular bias, and more defined by spiritual insights? Has the factor of religious epistemology (the science of religious knowledge) received proper recognition in the whole structure of studies? A major obstacle to voluntary support of church-related colleges lies in the fact that many such institutions do not differ sufficiently from non-Christian colleges and universities either in emphasis or in quality to merit special distinction and preference. Colleges with a virile evangelical dedication often stir the loyalties of countless sacrificial donors; on the other hand those with a blunted spiritual orientation must rely more and more upon heavy denominational subsidies. This fact ought to indicate the administrative fallacy of telling constituents: “Support us so we can witness.” The campus that maintains its witness inspires support. If Protestant churches wish to identify themselves with higher education, they must work to keep their institutions within the orbit of the historic Christian faith and its implications for learning; otherwise they will become increasingly dependent upon secular sources of support. Unfortunately college administrators who demand denominational subsidies for their schools often find that denominational leaders in turn demand for the campus ideological support for their official outlook and theological temper. This is proper enough when a denomination remains dedicated to its historic confessions; it becomes disastrous, however, when educational institutions are no longer free to articulate their own heritage aggressively against ecclesiastical deviations. In an age of transition church-relatedness and church-dependence thus tend to multiply both assets and liabilities.

While “church-related” is an ambiguous term, it is the diluted nature of the Christian content in the curriculum of many denominational institutions that has furnished special opportunity and status for some of the interdenominational evangelical colleges. Interdenominational institutions attract many students from denominational churches whose own schools often do not meet Christian expectations. Moreover, as the momentum of ecumenical merger overtakes many of the larger denominations, specific denominational emphases steadily lose vitality and validity for determining college preferences.

But in some cases the evangelical interdenominational colleges are squandering their opportunities. Even when resisting government funds for basically significant reasons, some of them, while determined neither to surrender nor to compromise constructive Christian emphases and values, confine their long-range planning merely to physical and academic changes. Happily, their objectives often include realistic faculty salaries and offices that permit full-time devotion to research, teaching, counseling and writing. But in some institutions, faculty retention has become no less a problem than faculty recruitment—one school has lost almost half its faculty in five years. Pietists criticize a few of the better schools for over-intellectualism; that complaint, however, is seldom made by those who grade students’ exams! In fact, it is precisely the lack of intellectual challenge, the absence of a pervasive presentation of the Christian life view, that vexes superior students on these campuses. The student body is not stimulated to win the Christian heritage in a struggle against the prevalent secular trends. In the clash with alien theories of life and culture students evaluate 1975 more in terms of Khrushchev’s threatened target date to conquer the Free World than within the sword and fire of Christian initiative.

The nature of world events is such that thinking students will not be captured for the Christian cause simply by hearing simple questions and hurried answers. An unearned and unwon heritage is soon surrendered and forfeited. Christian colleges today need a far deeper awareness than the Kremlin concerning education’s strategic role in gaining the mind of modern man, in realizing a new and deeper dedication to academic earnestness, in engendering a new classroom spirit that expects both teacher and student to justify their intellectual and moral commitments. Far more compellingly than Communism, Christian education must exhibit the fundamental unity of all knowledge; this is no time for academic ‘smörgåsbord.’ Christian colleges must so inspire students to zestful encounter with truths and the Living Truth that they will become bearers of hope to the world of our day. Without such an awakening and revitalization of vision, the Christian colleges—however much their literature may boast of superior education—may as well close their doors. The overarching function of the Christian campus is hardly to teach the elemental do’s and don’t’s of morality, nor the dangers of mating with an unbeliever, nor the techniques of evangelism, nor the outlines of a Bible handbook. These A-B-C’s are the proper ministry of the local church. The primary responsibility of the Christian college is so to communicate the content and technique of learning that students not only read Plato, Dewey, and Darwin unafraid, but yearn and are able to match their mettle with those who are devoid of Christian truth and experience in their lives. Far more important to good teaching than faculty-student ratio is the caliber of instruction. A saying at mammoth University of California (Berkeley) notes it is better to be 50 feet from a great teacher than five from a mediocre one. Great teaching is indeed the biggest vacuum in many Christian colleges.

Nothing less is needed than instruction that so grips the youth of tomorrow with the relevance both of the scientific spirit and of revealed doctrine that young people recognize that either without the other spells disaster for the twentieth century. When the academic community succumbs to pietistic domination, by concentrating on Christian virtue or on mere avoidance of the vices of the world, it violates its witness to the triumph of Christian truth. When teachers are less interested in a mastery of the content of learning than in evangelism a campus is likely to resound only with a rhetorical repetition of questions and answers. Dr. W. Harry Jellema, one of CHRISTIANITY TODAY’s contributing editors, recently warned against education which settles for “the learning of answers without sweating about the questions.” A Christian faculty must recognize that academic witness to the truth is fully as important as ringing doorbells. No simple parroting of questions and answers, no mere verbal echoes, will keep the Christian heritage vigorously alive.

CHRISTIANITY TODAY believes that American Christians can voluntarily support a program of Protestant higher education far greater than anything yet achieved. We believe they are increasingly troubled, however, by the hard news of educational statistics. Whereas one in two students was in a private college ten years ago, only one in five will be in a private college by 1970, of this group (one-fifth of the total collegiate enrollment) only a small percentage will be in Christian colleges. By 1970, moreover, the colleges and universities will enroll 7 million students, contrasted with the record of 3 million in 1960. Devout American Christians are concerned by these trends in a secular age. And, as we have said, we believe that believers in America have sufficient funds to support a strong program of evangelical higher education. The real question that Protestant denominational leaders must ask and answer is simply this: Why are American Christians reluctant to invest their money in church-related colleges?

August Alive With News As Most Ministers Vacation

If anyone was still unconvinced that this is a fast-moving world, the month of August provided the necessary persuasion. While many ministers found their annual vacation respite, news broke at a great pace. Marilyn Monroe’s suicide was scarcely forgotten when the record flight of the Soviet space twins preempted the headlines. Even developments superficially secular had, at a closer look, some religious implications. The Dutch-Indonesian pact over New Guinea, for instance, left unsure the future of missionary activity there.

On the religious front, the forthcoming Vatican Council picked up promotional steam as various non-Catholic groups announced their choice of observers. In a surprising deadlock in Athens, however, the Holy Synod of the Greek Orthodox Church adjourned without replying to the Vatican invitation for delegate-observers. In Rome, Pope John XXIII became first pontiff to receive a Shinto high priest when he granted audience to Dr. Shizuka Matsubara, head of the Ken-kun Shrine in Kyoto, Japan. In Moscow, Dr. Arthur Michael Ramsey, first Archbishop of Canterbury to set foot in the U.S.S.R., signed a joint appeal for closer ties between Anglican and Orthodox churches with Patriarch Alexei.

The church-state front in Poland once again was tense as the government announced it would take over all schools and orphanages within a year. Several convents and nurseries in the Warsaw area were being closed down.

Two high-ranking Anglican clergymen were expelled from Ghana after they condemned the deification of President Kwame Nkrumah by a government-sponsored youth organization. Three African Methodist ministers were released from prison in Angola after about a year’s detention on charges of subversive activities against Portuguese authorities.

The Israeli Parliament (Knesset) appointed a committee to look into Christian missionary activities. One legislator had charged the government with being “indifferent” to the fact that “more than 1,000 Jewish children are in Christian missionary institutions.”

In Australia, the Anglican and Roman Catholic archbishops of Perth made a joint appeal to the Province of Western Australia for state aid to church-related schools. The plea followed closely upon developments in New South Wales, where Roman Catholic parochial schools were closed for a week in a demonstration protest against the provincial government, which has refused aid.

A nine-year ban of the showing of the film “Martin Luther” in the Canadian province of Quebec was lifted by the new Quebec Film Censorship Board, made up entirely of Roman Catholics.

On the U. S. front, a number of ministers became involved in the civil liberties controversy in Albany, Georgia. The controversy’s key figure, Baptist minister Martin Luther King, Jr., became the first American Negro ever to speak to the National Press Club in Washington.… A new church was formed by the majority faction which, despite a two-year legal battle, lost control of the First Baptist Church of Wichita, Kansas after protesting American Baptist Convention affiliation with the National Council of Churches.

Spain’s new ambassador to the U. S. told the National Press Club that “we (Catholics) … have committed errors and “are now … establishing a status for Protestants that they have the right to have,” then sent a “corrected” text to the Washington Post stating: “We … may have committed some errors … but we will avoid … such misunderstandings and will give Protestants the position that they have the right to have … under Spanish laws.” He altered in print what he had told the newsmen publicly.

Three hundred years ago, on August 19, 1662, at the age of 39, Blaise Pascal died. What significance does this remarkable Christian thinker and man have for our own day? Often called a scientific genius, Pascal was much more concerned with the mystery of faith than with science. In his intense interest in the problems of faith, Pascal was a truly ecumenical figure. His significance is not confined to the Roman Catholic Church, but reaches to everyone who is involved with the question of how a man comes to believe. In short, Pascal must interest anyone who is concerned with an apologetic for the Christian faith.

This man did not live in mystical isolation from the world. He was ever concerned about the unbeliever. He intended, in fact, to write a defense of the Christian faith for the unbeleiver, but never completed his work. His incomplete work, however, has been left behind in fragmentary form. It is his famous Pansées. If all he left us was his struggle towards the formation of an apologetic, Pascal would merit our attention to this day.

Christians have always asked whether a man simply believes in spite of reason, or whether faith contains its own implicit rationale. The traditional conclusion of Pascal’s Roman Catholic community was that the preface to saving faith was potentially the common possession of all rational men. While the complete content of faith was not rationally demonstrable to all men, certain elements, such as God’s existence, were considered capable of proof. Pascal was unable to accept the rational route to faith. He insisted that the decision of faith took place, not in reason, but in the heart. This is the aspect of Pascal that captures the interest of Roman Catholic as well as Protestant thinkers today.

Roman Catholic theologians are experiencing serious doubts about the usefulness of the traditional proofs for God’s existence. Apart from the logical cogency of the proofs themselves, the question haunts many: what kind of God is actually proven by them to exist? What is one to think of a first cause or a prime mover at which unaided human thought arrives? Questions like these were posed by Pascal in his day and are being asked again in ours. As Pascal was led to question the traditional proofs because of them, they are again leading to doubt about the rational aids to faith. Hence, Pascal’s contemporaneity.

But where did Pascal go after rejecting the proofs? Was faith, for him, wholly irrational? Does a man believe only because he happens to will to believe? Is there no genuine dialogue between the believer and the unbeliever? Do believer and unbeliever inhabit two different worlds with no communication between them? Is there no apologetic? Pascal did believe that there was an effective apologetic for the Christian faith even though he rejected the traditional one.

Before going further, we ought to remind ourselves that we have the same problem. When we forsake the traditional proofs for God, do we forsake all genuine apologetic? Once we reject the existence of a rational area common to believer and unbeliever, do we not break off meaningful conversation with the unbeliever? If belief is a matter only of the heart’s decision, can there be a rational dialogue about the content of faith? Does not, as Pascal said, “the heart have reasons which the reason does not know?”

Pascal did indeed have an apologetic. He did engage in dialogue. He talked, not to an abstract thing called reason, but to the actual, the concrete person. He pointed that person to his own greatness and misery (grandeur et misere de l’homme). He uncovered his fallenness from his original grandeur and exposed him as a “dethroned king.” Man’s own need, his own misery, his unfilled longing, his unrest, and his rebellion—to these Pascal directed man’s thought. Pascal is not occupied with the reason. His method stems from faith itself. But he intended to put his finger on the reality of man as he actually existed, fallen and miserable and in sin.

Unbelief and misery do not, for Pascal, form a neutral point of contact for grace, as though they can be easily disposed toward an easy decision for faith. But Pascal did speak directly to man in his misery and unbelief. He knew the nature of man’s fall and redemption and knew that fallen man had nothing in him to dispose him to salvation. But the witness of Jesus Christ encountered man in his misery, breaking through and becoming manifest there as the new Light of life. This insight Pascal leaves behind and it interests us intensely.

We are not dealing with an argument used to force men to accept the cogency of faith’s rationale. However academically interesting such an argument might be, Pascal knew that it could never overcome the resistance of unbelief. But he was not willing to break off conversation. His apologetic was tied to witnessing. Apologetics and witness met, not in the natural light of reason, but in the misery of fallen man.

Pascal did not deny the greatness of man, but he acknowledged his greatness only within the depths of his misery. We, in our day, know something of man’s greatness as Pascal was not able to know it. Man’s greatness seems to shine through his fantastic technical achievements, an aspect to man’s accomplishments at which Pascal could not have guessed. But Pascal’s vision is still relevant. For the “uncrowned king” is still great only in his poverty, in his threatened existence, and his unfulfilled pretensions. The “grand man” is clearly the man without God. For this reason too, we read Pascal these days.

Pascal placed a problem on the agenda which cannot leave us indifferent. It is the problem of the profound divorce between man and man, between belief and unbelief, and of the possibility of conversation between them. We know today of man’s profound need, of his finitude, of his isolation and estrangement. Existentialism has had a great deal to say about man’s limitations and estrangement. But there is a deep difference between Pascal and modern existentialism. Existentialism accepts man in his need and finitude and calls him to freedom. Pascal sees man in his need and sin and calls him to grace. The freedom concept of atheistic existentialism distinguishes Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir from Pascal. The latter’s interpretation of man calls attention, not to man’s finitude first of all, but to man’s guilt, calls man not to the freedom he has, but to the freedom he has lost. Pascal addresses man in his undeniable misery and points him to the Gospel’s saving light, the Light of the world.

Pascal looms as a truly ecumenical Christian thinker. He dealt with problems relevant to all times. Freeing himself from traditional forms and methods, he sought better and more biblical ways. Though his significance for science and ethics remains as a phase in the history of human thought, his genuine contemporaneity lies in his apologetics, especially in his Pensées. A commemoration of a man’s death can be a good deal more meaningful than the recollection of a colorful historical memory. Commemoration of Pascal’s death and therewith a consideration of his thoughts and struggles sets us immediately into our own time.

In our one world, men’s thoughts and actions touch each other on every terrain. Is our encounter with men one in which we discover that one man believes and the other does not, with no real reason for either? Pascal had an answer. His answer takes the form of a witness. He recognized the resistance of the human heart to God. And he knew that what he had to do was not to prove the rationality of an idea, but to witness to the living God, the father of Jesus Christ. “Not the god of the philosophers, but the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob.” These are words from Pascal’s Memorial of 1654 which was discovered at his death, a fragment that he had carried with him for eight years.

In the Memorial such positive sounds as certainty and, especially, joy are accented. His God was not an idea, but a Person; his faith was not the capstone of an intellectual structure, but the reality which is in Christ. The certainty and joy that permeated Pascal’s brief life places us in our own time—which in its way is also brief—before the question of our own certainty and joy, and before the question of our readiness to respond to God’s call in our God-estranged world. This too is the calling we hear as we commemorate the death of Pascal.

G. C. BERKOUWER

Free University of Amsterdam

Amsterdam, The Netherlands

The 1962 Washington conference of International Christian Leadership featured a panel discussion on “Christianity in Higher Education.”CHRISTIANITY TODAYhere presents significant excerpts from comments by the four participants, Former U.S. Senator Ralph E. Flanders of Vermont, Professor H. Maurice Carlson of Lafayette College, Professor John Brobeck of University of Pennsylvania, and President James Forrester of Gordon College.

THE ACADEMIC CLIMATE—I have an intense interest in the particular subject of the relation between the Christian religion and modern education. I had the great privilege and responsibility a year ago last fall of serving as Visiting Professor in Practical Politics at the University of Massachusetts, located at Amherst, the same town of Amherst College. I was required at the end of November and December to give four public lectures and I chose as my topic, “The Moral Law in the modern World.” After I delivered the four lectures, one student after another told me that their professors in Sociology and Philosophy tell them that there is no moral law and that there are no absolutes. That is the atmosphere in which young people get their education.

Some of the most eminent members of the Supreme Court have said substantially the same thing. Oliver Wendell Holmes denied that there are any absolute rights and wrongs to which appeal can be made by the courts. In one of his judgments Chief Justice Vinson, whom I knew personally and respected as a person, said in effect, “If there is anything that is well established, it is that there are no absolutes.” Now that is the intellectual atmosphere in which far too many of our young people are growing up.—Former U.S. Senator RALPH E. FLANDERS of Vermont.

THE CLAIMS OF CHRIST—One of the most thoughtful modern historians has suggested that civilization now finds itself where John Bunyan’s Christian found himself almost three centuries ago, “I dreamed, and behold I saw a man clothed with rags, standing in a certain place, with his face from his own house, a book in his hand and a great burden upon his back. I looked and saw him open the book and read therein, and not being able longer to contain, he broke out with a lamentable cry, saying, ‘What shall I do?’ ” (Arnold J. Toynbee, A Study of History, Vol. VI, p. 320. Oxford University Press, 1939).

Into this world of uncertainty for which history through the years offers little or no hope, our educational system each year thrusts thousands of young people. Our hope is in our youth and thus it has always been. Are they equipped to bring order out of chaos, understanding out of misconception, love out of hate?

Dr. Louis Evans of the Hollywood Presbyterian Church in a recent address in Easton, Pennsylvania, told of being in the Orient in 1960 and eating dinner in a restaurant with a man from Osan, an agricultural finance agent from the U.S. who was waiting to get back to Laos, waiting for the revolution to subside. Dr. Evans asked, “How are things?” “Not good,” was the reply. “They are seeping down from the north. I never saw such ‘missionaries’ in my life, they permeate, they debate, they argue. They have vowed to invite at least ten people over to dinner every week and they draw up their chairs after dinner and persuade some more and give out free leaflets and books. They are sweeping Laos.”

“Well,” said Dr. Evans, “why don’t you counter with what you believe?”

He said, “Dr. Evans, I don’t know what I believe and I’m a Ph.D. How can I fight their convictions with my vacuum? I’m a washout and so is every businessman abroad.” Dr. Evans said earlier, “The most embarrassing question that I can ask a college senior is, ‘What are you living for man? Give me your philosophy of life?’ A lot of them don’t even know, in a day when others are dying for their convictions.”

The American Council on Education has noted that there is no marked difference in the religious concept of the average pupil in the eighth grade of school and the average college graduate (Report by Louis Gale, Cleveland Plain Dealer, August 21, 1949).

President Conant of Harvard in the spring of 1943 appointed a committee on Objectives of General Education in a Free Society. From the report: “The ideal of free inquiry is a precious heritage of Western culture, yet a measure of firm belief is surely a part of the good life. A free society means toleration which in turn comes from openness of mind. But freedom also presupposes conviction: a free choice—unless it is wholly arbitrary—comes from belief and ultimately from principle.… A measure of belief is necessary to preserve the quality of the open mind” (General Education in a Free Society. Report of the Harvard Committee, pp. 77, 78. Harvard University Press, 1945). And yet in a recent questionnaire on religious and political attitudes at Harvard and Radcliffe in which 310 students chosen at random participated of whom 183 were Protestants, 39% of these Protestants stated that they had left their Protestantism and most considered themselves to have no faith at all (The Harvard Crimson).

The young people in our colleges and universities are not coming to grips with the fundamental issues of life. It is important that these young people be given the opportunity of making a choice but all too often in our higher education, they don’t have this opportunity.

Robert M. Hutchins in his report “The Relation of Religion to Public Education” says “The higher learning in America has developed a broad urbanity, an all engulfing tolerance which finds it easy to be hospitable to everything except conviction—and genuine conviction, which must not be confused with intolerance, is one of the crying needs of our age” (Robert M. Hutchins, The Relation of Religion to Public Education by the Committee on Religion and Education of the American Council on Education, Series 1, No. 26, April, 1947, p. 41).

What then is the answer? I propose three approaches:

1. There must be a real effort on the part of the colleges and universities to provide an adequate place in the curriculum for this dimension so lacking today. As Howard Lowry of Wooster College has said in such a pointed way, “An adequate place in the curriculum means a department of religion, with personnel of high quality, comparable to that of other academic departments. It means a sufficient offering of courses (not all necessarily in the department) in the Bible, comparative religion, the philosophy and the psychology of religion, Christian ethics, church history, the history of Christian thought and the like. The course in Bible, incidentally, would be more than a course in Bible as literature. It would be a course in the Hebrew-Christian conception of life.”

“Genuine curricular acceptance of religion would involve also the securing of some adequate attention to religion in the other courses of the university where it is germane. There are many such courses, where consideration of religion, necessary to the understanding of the matter at hand, is not something for the teacher to include or ignore according to his own whim, but to take account of because it is his professional duty” (Howard Lowry, The Mind’s Adventure, p. 94, The Westminster Press, 1950).

2. The individual teacher occupies a very important place in influencing the lives of our college young people. It has often been said that we teach more by precept and example than by the spoken or written word. The faculty member who is a committed Christian, who recognizes his potential influence in the lives of young people can relate Christian thought and consideration to the subject he presents daily in the classroom, yet without preaching. It is important that he have the freedom to do this, in the framework of the discipline in which he finds himself. Qualified, committed Christian teachers are urgently needed in all areas of college education.

3. For those teachers who live on or near the campus there is the opportunity to invite students into their homes for study and discussion of the fundamental issues of life, providing a natural avenue for the consideration of the claims of Christianity, the claims of the person of Jesus Christ upon their lives.

In the final analysis, it is with Him whom we must reckon, be it university, teacher or individual. If Christ were only a good man or the best teacher then our education need only give passing mention to Him, but if He is who He claims to be, the Son of God, the One for whom all history was preparing, the One who divided time into the before and after, the One who said, “I am the Way, the Truth, and the Life: no man cometh unto the Father, but by me,” then it is essential, that the college and university and those of us who teach therein, and we as individuals give ear to Him of whom it is said, “This is my beloved Son, hear ye Him.”—Professor H. MAURICE CARLSON, Head of the Mechanical Engineering Department, Lafayette College, Pennsylvania.

EVANGELICAL FAILURES—I have been in the Christian community for nearly 50 years. In these 50 years I have heard the universities blamed very often for hostility to Christianity. There is some truth in the charge. But this kind of sniping or shooting from the Christian community has done little to increase the means or to strengthen the techniques of communication between these two groups. It is my own impression that if this situation is going to be remedied, it must be attempted first on the part of the Christian community. Evangelical Christians have a limited influence at the present time in the university community; in fact, in some cases one can say that we have no influence, and we cannot expect the universities to come to us.

The nature of this lack of communication can be illustrated, I believe, by the almost complete ignorance that both of these groups have of the other. If you were to ask the first ten people you met on any ordinary university campus to state in two sentences the evangelical Christian position, most of them probably could not give you anything close to a correct answer. But if you ask the devout members of the ordinary, evangelical or fundamental church (the kind of church our family belongs to) what’s going on in universities, they will not know that either. Because I have had a disappointing personal experience in this regard, it is possible for me to speak to you from a sense of personal frustration.

We live in a relative center of Christian education in and around Philadelphia, with seminaries, Christian colleges, and Bible schools in our neighborhood. Not once have I been asked to come to any one of these schools to discuss with their students, many of them going into the ministry or to the mission field, any subject related to the development of modern science. (Perhaps they have reason to think that I do not know!) By contrast, I am often asked—in fact, my wife wishes that I got only a tenth of the invitations—to go to universities, medical schools and colleges, and I have many opportunities to witness as a Christian in these secular institutions. But I have never had any opportunity to witness as a scientist in a seminary or Bible school. I believe that illustrates simply that Christians are not interested in science or scientists. Among my Christian friends there is a considerable mistrust and possibly even a fear of the university idea. There is even a mistrust of higher education in general. For example, many Christian people will not admit that we need good, strong Christian schools and colleges, and that we must provide their support! If you ask these Christian friends why they do not give more liberally to their schools, they may answer, “If they get wealthy they’ll become like Harvard.” This kind of ignorance and prejudice is made to justify a lack of adequate support. Even more serious, however, is the fact that if someone were to give a hundred million dollars for endowment of a Christian college, the money could not be spent effectively because of a shortage of qualified, Christian scholars. Not only is our Christian community not producing the money, it is not producing the teachers and investigators. I suppose that this failure, too, results from mistrust, suspicion, or fear of higher education.

I question whether we can influence the course of the great universities by anything Christians may write or say, or by any kind of public educational campaign. But I suggest that we may have some hope under God of influencing the attitude of our Christian friends, and of getting them to realize that they are getting no more than they are paying for in higher education. If they want something more, if they want something better, it will cost money, it will take time, it will require men. The Christian community can do it if we really put our hearts and our souls into this kind of effort.—Dr. JOHN BROBECK, Chairman of the Department of Physiology, School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania.

HONORING ALL THE TRUTH—We are in a crisis in which the difference between and the relation between what has classically been called “knowledge” and “wisdom” have become very important. In the past the university has concerned itself with these together, the conjunction giving them equal value. Historically Greek influences have predominated and now the scientific methodology, added to these, directs higher education into a major dominant concern for “knowledge” with perhaps an unwitting suppression of “wisdom.”

I understand that after the Nazi war crimes trials in Europe Justice Robert H. Jackson said that “the paradox of modern society is that modern society has to fear the educated man.” This is heresy amongst educators. Yet, “knowledge” without “wisdom” could very well lead us to a kind of technological splendor which would be only the precursor of disaster. This is everywhere evident, it is everywhere talked about. We, therefore, have an obligation to consider the relation of values and of Christian values for the whole process of higher education as we know it, and the university’s obligation to present the truth to students without suppression of any part of it.

One of the distinctives of our culture is that it has been so strongly influenced by Christianity and that the university movement itself grew out of the Church. In the beginning higher education in the United States was virtually born through the influence of men of profound religious convictions. The spiritual emphases were dominant in the founding of Harvard and in the subsequent founding of Yale and other later universities which have come to prominence. It seems strange that with this kind of beginning there should now develop a self-consciousness among higher educational people over the discussion of religious truths, and that we should have found it necessary to prescribe legal controls for some tax-supported institution with respect to the matter of religious expression. The universities in our country seem in the main to be uncertain whether they have any responsibility to say anything in the area of moral and spiritual values. If truth is to be defined in relation to the fundamental categories of existence, then the university cannot fulfill its obligation to confront students with all the truth without dealing with the theistic hypothesis as having a dimension perhaps not amenable to the scientific methodology procedures.

It seems to me that certain fallacious assumptions underlie the problem in America in the prevalent avoidance of dimensions of truth which relate to values. To become aware of these might help us to move toward some constructive answers.

1. One of these assumptions is that total objectivity is fundamental to the image of the intellectual. The Christian faith may be examined discursively, and private interest in it has been permitted on most university campuses. But the Christian professes relationship with God the Father and the discovery of God in the revelation of God in Jesus Christ and in the revealed word of Holy Scripture. To eliminate these things from Christian perspective is to give us a watered down kind of ethnic religion. Whereas objectivity is a virtue to the intellectual, the subjective experiences which are necessary components of the Christian religion should be elevated at least to some legitimate level of recognition with those things that are the objective criteria by which we operate in the intellectual world. It is supposed that if one passionately holds a world view that excludes divine revelation one is objective and scholarly, but conversely if one holds the broader view, which allows the intersection of human experience by God in Jesus Christ, one is automatically classed as being biased and doctrinaire.

2. A second fallacious assumption is that we must choose between a Christian anti-intellectualism and an anti-Christian intellectualism as though this were the either/or of intellectual possibility on the university campus. If on a given campus the compulsion to be intellectual is dominant on the basis of this assumption, one is committed automatically to an anti-Christian position; one cannot endorse Christianity openly without being intellectually suspect. Likewise, the Christian institution which accepts the intellectual pursuit as being dangerously subversive to intellectual values is likely to move in an anti-intellectual direction. We must challenge this false antithesis if we are to proceed to constructive answers to the question of the university’s contribution in this area and of the relationship of Christianity to the modern American university. We are not forced to choose between a Christian anti-intellectualism and an anti-intellectual Christianity.

3. A third fallacious assumption is that academic freedom requires the repudiation of anything which is religiously doctrinaire. It is significant to me that where this dogma of academic freedom has been argued most strongly economic or social dogma or points of view are presented with all the force of indoctrination. But in the same context the insinuation of religious concepts must be outlawed on the grounds of academic freedom! This fallacy needs to be reevaluated.

4. A fourth assumption is that technical competence is more important than moral power. We are not afraid of atomic information in the hands of morally motivated persons or persons who have Christian values or Christian motivation. We are afraid of its potentiality for human and property and value destruction in the hands of people who have no moral controls of the Christian kind. Somehow or another we must insinuate Christian values into our technological culture so that it is not amoral but moral.

There should be a place in the university curriculum for the Christian religion in the context of our culture. This, incidentally, is occurring across the country more and more; even tax-supported campuses are offering courses in religion with college credit. There has been a greater encouragement to denominational groups for representation in a proper and orderly way on campus. There has been the encouragement of campus chaplains and greater freedom has been given to these men to operate with the students in the last fifteen years. The initiative in this must lie with the Christian educators. It is not to be supposed that the secular educator, who has not the same concern for the Christian values as the Christian educator, is likely to be sufficiently aware of what might be done to initiate something in this regard. Christian educators must first educate their own constituencies so that the intellectual pursuits are not to be equated with heresy. There needs to be communication of the proper meanings of academic freedom to the supporting constituencies of Church-related institutions. We can enter into interchange with regional associations, and express ourselves in the free atmosphere of the Association of American Colleges. The Protestant college group can deal with this issue openly and in the context of the larger association of colleges and universities. Then we must form some articulate voice for the Christian claim in higher education. We must express clearly the kerygmatic faith, the New Testament thrust with all its daring assumptions—not a watered down, minimized faith suitable only for comparative purposes with the other ethnic religions. We must, as Christians, put these concepts into the market of free ideas without the anxiety that they cannot make their way.—President JAMES FORRESTER, Gordon College, Beverly Farms, Massachusetts.