Just over 200 years ago the French philosopher-physician Lamettrie published his daring book, L’Homme Machine. He was a thoroughgoing materialist, as the title of his book suggests; and like everyone of his kind—from Democritus in ancient Greece to Bertrand Russell in our own day—he denied the spiritual principle in man, regarding the human organism as nothing more than complicated machinery.

Even in his presumably “enlightened” age this teaching was too much for many people, and Lamettrie fearing persecution left his native land to live as an exile in Berlin. But were the French savant living today, he would not find his theory altogether unpopular; and he could write about “Man the Machine” with little fear of being penalized for so doing. He would find support in many quarters, not least among people known as “Cyberneticists.”

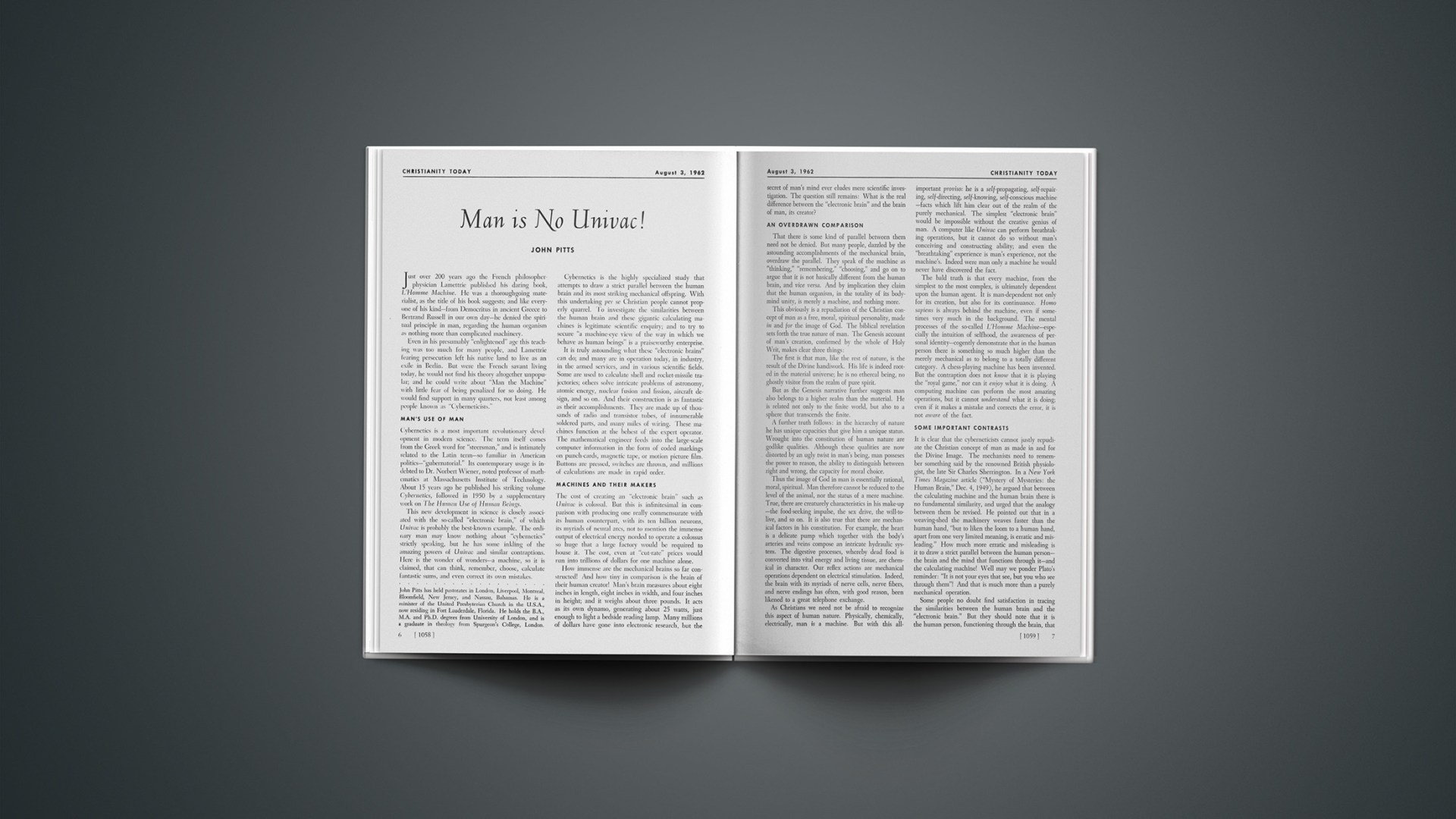

Man’S Use Of Man

Cybernetics is a most important revolutionary development in modern science. The term itself comes from the Greek word for “steersman,” and is intimately related to the Latin term—so familiar in American politics—“gubernatorial.” Its contemporary usage is indebted to Dr. Norbert Wiener, noted professor of mathematics at Massachusetts Institute of Technology. About 15 years ago he published his striking volume Cybernetics, followed in 1950 by a supplementary work on The Human Use of Human Beings.

This new development in science is closely associated with the so-called “electronic brain,” of which Univac is probably the best-known example. The ordinary man may know nothing about “cybernetics” strictly speaking, but he has some inkling of the amazing powers of Univac and similar contraptions. Here is the wonder of wonders—a machine, so it is claimed, that can think, remember, choose, calculate fantastic sums, and even correct its own mistakes.

Cybernetics is the highly specialized study that attempts to draw a strict parallel between the human brain and its most striking mechanical offspring. With this undertaking per se Christian people cannot properly quarrel. To investigate the similarities between the human brain and these gigantic calculating machines is legitimate scientific enquiry; and to try to secure “a machine-eye view of the way in which we behave as human beings” is a praiseworthy enterprise.

It is truly astounding what these “electronic brains” can do; and many are in operation today, in industry, in the armed services, and in various scientific fields. Some are used to calculate shell and rocket-missile trajectories; others solve intricate problems of astronomy, atomic energy, nuclear fusion and fission, aircraft design, and so on. And their construction is as fantastic as their accomplishments. They are made up of thousands of radio and transistor tubes, of innumerable soldered parts, and many miles of wiring. These machines function at the behest of the expert operator. The mathematical engineer feeds into the large-scale computer information in the form of coded markings on punch-cards, magnetic tape, or motion picture film. Buttons are pressed, switches are thrown, and millions of calculations are made in rapid order.

Machines And Their Makers

The cost of creating an “electronic brain” such as Univac is colossal. But this is infinitesimal in comparison with producing one really commensurate with its human counterpart, with its ten billion neurons, its myriads of neural arcs, not to mention the immense output of electrical energy needed to operate a colossus so huge that a large factory would be required to house it. The cost, even at “cut-rate” prices would run into trillions of dollars for one machine alone.

How immense are the mechanical brains so far constructed! And how tiny in comparison is the brain of their human creator! Man’s brain measures about eight inches in length, eight inches in width, and four inches in height; and it weighs about three pounds. It acts as its own dynamo, generating about 25 watts, just enough to light a bedside reading lamp. Many millions of dollars have gone into electronic research, but the secret of man’s mind ever eludes mere scientific investigation. The question still remains: What is the real difference between the “electronic brain” and the brain of man, its creator?

An Overdrawn Comparison

That there is some kind of parallel between them need not be denied. But many people, dazzled by the astounding accomplishments of the mechanical brain, overdraw the parallel. They speak of the machine as “thinking,” “remembering,” “choosing,” and go on to argue that it is not basically different from the human brain, and vice versa. And by implication they claim that the human organism, in the totality of its body-mind unity, is merely a machine, and nothing more.

This obviously is a repudiation of the Christian concept of man as a free, moral, spiritual personality, made in and for the image of God. The biblical revelation sets forth the true nature of man. The Genesis account of man’s creation, confirmed by the whole of Holy Writ, makes clear three things:

The first is that man, like the rest of nature, is the result of the Divine handiwork. His life is indeed rooted in the material universe; he is no ethereal being, no ghostly visitor from the realm of pure spirit.

But as the Genesis narrative further suggests man also belongs to a higher realm than the material. He is related not only to the finite world, but also to a sphere that transcends the finite.

A further truth follows: in the hierarchy of nature he has unique capacities that give him a unique status. Wrought into the constitution of human nature are godlike qualities. Although these qualities are now distorted by an ugly twist in man’s being, man posseses the power to reason, the ability to distinguish between right and wrong, the capacity for moral choice.

Thus the image of God in man is essentially rational, moral, spiritual. Man therefore cannot be reduced to the level of the animal, nor the status of a mere machine. True, there are creaturely characteristics in his make-up—the food-seeking impulse, the sex drive, the will-to-live, and so on. It is also true that there are mechanical factors in his constitution. For example, the heart is a delicate pump which together with the body’s arteries and veins compose an intricate hydraulic system. The digestive processes, whereby dead food is converted into vital energy and living tissue, are chemical in character. Our reflex actions are mechanical operations dependent on electrical stimulation. Indeed, the brain with its myriads of nerve cells, nerve fibers, and nerve endings has often, with good reason, been likened to a great telephone exchange.

As Christians we need not be afraid to recognize this aspect of human nature. Physically, chemically, electrically, man is a machine. But with this allimportant proviso: he is a self-propagating, self-repairing, self-directing, self-knowing, self-conscious machine—facts which lift him clear out of the realm of the purely mechanical. The simplest “electronic brain” would be impossible without the creative genius of man. A computer like Univac can perform breathtaking operations, but it cannot do so without man’s conceiving and constructing ability; and even the “breathtaking” experience is man’s experience, not the machine’s. Indeed were man only a machine he would never have discovered the fact.

The bald truth is that every machine, from the simplest to the most complex, is ultimately dependent upon the human agent. It is man-dependent not only for its creation, but also for its continuance. Homo sapiens is always behind the machine, even if sometimes very much in the background. The mental processes of the so-called L’Homme Machine—especially the intuition of selfhood, the awareness of personal identity—cogently demonstrate that in the human person there is something so much higher than the merely mechanical as to belong to a totally different category. A chess-playing machine has been invented. But the contraption does not know that it is playing the “royal game,” nor can it enjoy what it is doing. A computing machine can perform the most amazing operations, but it cannot understand what it is doing; even if it makes a mistake and corrects the error, it is not aware of the fact.

Some Important Contrasts

It is clear that the cyberneticists cannot justly repudiate the Christian concept of man as made in and for the Divine Image. The mechanists need to remember something said by the renowned British physiologist, the late Sir Charles Sherrington. In a New York Times Magazine article (“Mystery of Mysteries: the Human Brain,” Dec. 4, 1949), he argued that between the calculating machine and the human brain there is no fundamental similarity, and urged that the analogy between them be revised. He pointed out that in a weaving-shed the machinery weaves faster than the human hand, “but to liken the loom to a human hand, apart from one very limited meaning, is erratic and misleading.” How much more erratic and misleading is it to draw a strict parallel between the human person—the brain and the mind that functions through it—and the calculating machine! Well may we ponder Plato’s reminder: “It is not your eyes that see, but you who see through them”! And that is much more than a purely mechanical operation.

Some people no doubt find satisfaction in tracing the similarities between the human brain and the “electronic brain.” But they should note that it is the human person, functioning through the brain, that does the tracing. No machine can study the similarities between itself and its human creator. Or, if it does, it is only because a human hand, the tool of a human person, fed the data into the machine and threw the operating switches. The end result of the most intricate calculation consists of words, figures, symbols which mean nothing to the machine; they have meaning only for the scientist. Strictly speaking the machine does not calculate; it is the operator who calculates with the aid of the man-made machine. All that the machine does is to carry out the mechanical and electrical operations predetermined by its creator. No wonder a British electronics engineer calls his computer TOM—T.O.M. “Thoroughly Obedient Moron.”

The new science of cybernetics cannot justly gainsay the truth that under God man is a “creator.” Because he is made in the Imago Dei he shares in and mediates the creative power of the Almighty—a fact borne witness to by his science, his industry, his art, his architecture, and his literature. True, it is a limited creative power, dependent upon divinely provided material, but real nonetheless. And as a “creator under God” man is greater than any machine he creates. Well might Thomas Carlyle say of the human person: “We are the miracle of miracles—the great inscrutable mystery of God. We cannot understand it; we do not know how to speak of it; but we may feel and know, if we like, that it is verily so.”