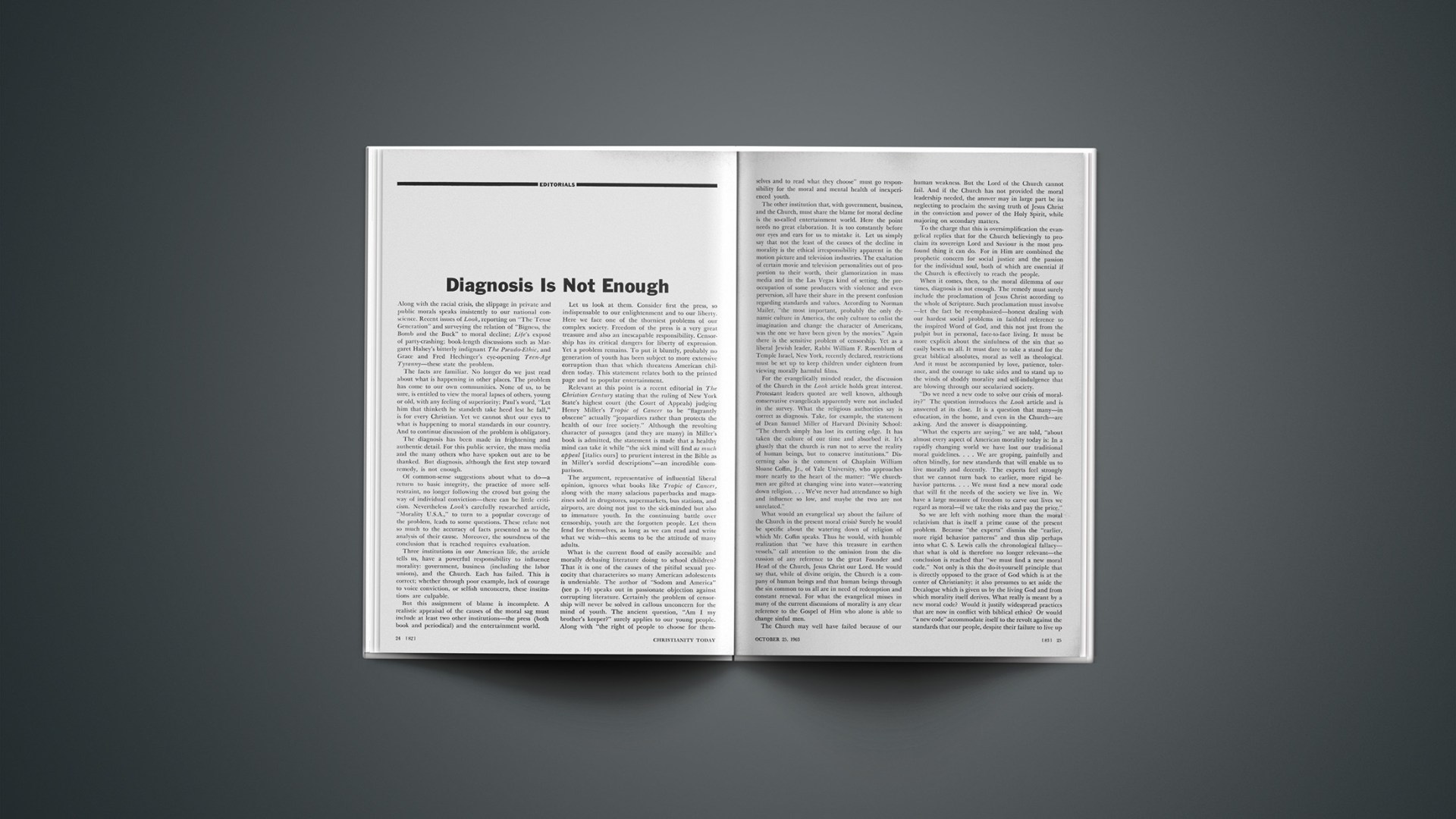

Along with the racial crisis, the slippage in private and public morals speaks insistently to our national conscience. Recent issues of Look, reporting on “The Tense Generation” and surveying the relation of “Bigness, the Bomb and the Buck” to moral decline; Life’s exposé of party-crashing; book-length discussions such as Margaret Halsey’s bitterly indignant The Pseudo-Ethic, and Grace and Fred Hechinger’s eye-opening Teen-Age Tyranny—these state the problem.

The facts are familiar. No longer do we just read about what is happening in other places. The problem has come to our own communities. None of us, to be sure, is entitled to view the moral lapses of others, young or old, with any feeling of superiority; Paul’s word, “Let him that thinketh he standeth take heed lest he fall,” is for every Christian. Yet we cannot shut our eyes to what is happening to moral standards in our country. And to continue discussion of the problem is obligatory.

The diagnosis has been made in frightening and authentic detail. For this public service, the mass media and the many others who have spoken out are to be thanked. But diagnosis, although the first step toward remedy, is not enough.

Of common-sense suggestions about what to do—a return to basic integrity, the practice of more self-restraint, no longer following the crowd but going the way of individual conviction—there can be little criticism. Nevertheless Look’s carefully researched article, “Morality U.S.A.,” to turn to a popular coverage of the problem, leads to some questions. These relate not so much to the accuracy of facts presented as to the analysis of their cause. Moreover, the soundness of the conclusion that is reached requires evaluation.

Three institutions in our American life, the article tells us, have a powerful responsibility to influence morality: government, business (including the labor unions), and the Church. Each has failed. This is correct; whether through poor example, lack of courage to voice conviction, or selfish unconcern, these institutions are culpable.

But this assignment of blame is incomplete. A realistic appraisal of the causes of the moral sag must include at least two other institutions—the press (both book and periodical) and the entertainment world.

Let us look at them. Consider first the press, so indispensable to our enlightenment and to our liberty. Here we face one of the thorniest problems of our complex society. Freedom of the press is a very great treasure and also an inescapable responsibility. Censorship has its critical dangers for liberty of expression. Yet a problem remains. To put it bluntly, probably no generation of youth has been subject to more extensive corruption than that which threatens American children today. This statement relates both to the printed page and to popular entertainment.

Relevant at this point is a recent editorial in The Christian Century stating that the ruling of New York State’s highest court (the Court of Appeals) judging Henry Miller’s Tropic of Cancer to be “flagrantly obscene” actually “jeopardizes rather than protects the health of our free society.” Although the revolting character of passages (and they are many) in Miller’s book is admitted, the statement is made that a healthy mind can take it while “the sick mind will find as much appeal [italics ours] to prurient interest in the Bible as in Miller’s sordid descriptions”—an incredible comparison.

The argument, representative of influential liberal opinion, ignores what books like Tropic of Cancer, along with the many salacious paperbacks and magazines sold in drugstores, supermarkets, bus stations, and airports, are doing not just to the sick-minded but also to immature youth. In the continuing battle over censorship, youth are the forgotten people. Let them fend for themselves, as long as we can read and write what we wish—this seems to be the attitude of many adults.

What is the current flood of easily accessible and morally debasing literature doing to school children? That it is one of the causes of the pitiful sexual precocity that characterizes so many American adolescents is undeniable. The author of “Sodom and America” (see p. 14) speaks out in passionate objection against corrupting literature. Certainly the problem of censorship will never be solved in callous unconcern for the mind of youth. The ancient question, “Am I my brother’s keeper?” surely applies to our young people. Along with “the right of people to choose for themselves and to read what they choose” must go responsibility for the moral and mental health of inexperienced youth.

The other institution that, with government, business, and the Church, must share the blame for moral decline is the so-called entertainment world. Here the point needs no great elaboration. It is too constantly before our eyes and ears for us to mistake it. Let us simply say that not the least of the causes of the decline in morality is the ethical irresponsibility apparent in the motion picture and television industries. The exaltation of certain movie and television personalities out of proportion to their worth, their glamorization in mass media and in the Las Vegas kind of setting, the pre-occupation of some producers with violence and even perversion, all have their share in the present confusion regarding standards and values. According to Norman Mailer, “the most important, probably the only dynamic culture in America, the only culture to enlist the imagination and change the character of Americans, was the one we have been given by the movies.” Again there is the sensitive problem of censorship. Yet as a liberal Jewish leader, Rabbi William F. Rosenblum of Temple Israel, New York, recently declared, restrictions must be set up to keep children under eighteen from viewing morally harmful films.

For the evangelically minded reader, the discussion of the Church in the Look article holds great interest. Protestant leaders quoted are well known, although conservative evangelicals apparently were not included in the survey. What the religious authorities say is correct as diagnosis. Take, for example, the statement of Dean Samuel Miller of Harvard Divinity School: “The church simply has lost its cutting edge. It has taken the culture of our time and absorbed it. It’s ghastly that the church is run not to serve the reality of human beings, but to conserve institutions.” Discerning also is the comment of Chaplain William Sloane Coffin, Jr., of Yale University, who approaches more nearly to the heart of the matter: “We churchmen are gifted at changing wine into water—watering down religion.… We’ve never had attendance so high and influence so low, and maybe the two are not unrelated.”

What would an evangelical say about the failure of the Church in the present moral crisis? Surely he would be specific about the watering down of religion of which Mr. Coffin speaks. Thus he would, with humble realization that “we have this treasure in earthen vessels,” call attention to the omission from the discussion of any reference to the great Founder and Head of the Church, Jesus Christ our Lord. He would say that, while of divine origin, the Church is a company of human beings and that human beings through the sin common to us all are in need of redemption and constant renewal. For what the evangelical misses in many of the current discussions of morality is any clear reference to the Gospel of Him who alone is able to change sinful men.

The Church may well have failed because of our human weakness. But the Lord of the Church cannot fail. And if the Church has not provided the moral leadership needed, the answer may in large part be its neglecting to proclaim the saving truth of Jesus Christ in the conviction and power of the Holy Spirit, while majoring on secondary matters.

To the charge that this is oversimplification the evangelical replies that for the Church believingly to proclaim its sovereign Lord and Saviour is the most profound thing it can do. For in Him are combined the prophetic concern for social justice and the passion for the individual soul, both of which are essential if the Church is effectively to reach the people.

When it comes, then, to the moral dilemma of our times, diagnosis is not enough. The remedy must surely include the proclamation of Jesus Christ according to the whole of Scripture. Such proclamation must involve—let the fact be re-emphasized—honest dealing with our hardest social problems in faithful reference to the inspired Word of God, and this not just from the pulpit but in personal, face-to-face living. It must be more explicit about the sinfulness of the sin that so easily besets us all. It must dare to take a stand for the great biblical absolutes, moral as well as theological. And it must be accompanied by love, patience, tolerance, and the courage to take sides and to stand up to the winds of shoddy morality and self-indulgence that are blowing through our secularized society.

“Do we need a new code to solve our crisis of morality?” The question introduces the Look article and is answered at its close. It is a question that many—in education, in the home, and even in the Church—are asking. And the answer is disappointing.

“What the experts are saying,” we are told, “about almost every aspect of American morality today is: In a rapidly changing world we have lost our traditional moral guidelines.… We are groping, painfully and often blindly, for new standards that will enable us to live morally and decently. The experts feel strongly that we cannot turn back to earlier, more rigid behavior patterns.… We must find a new moral code that will fit the needs of the society we live in. We have a large measure of freedom to carve out lives we regard as moral—if we take the risks and pay the price.”

So we are left with nothing more than the moral relativism that is itself a prime cause of the present problem. Because “the experts” dismiss the “earlier, more rigid behavior patterns” and thus slip perhaps into what C. S. Lewis calls the chronological fallacy—that what is old is therefore no longer relevant—the conclusion is reached that “we must find a new moral code.” Not only is this the do-it-yourself principle that is directly opposed to the grace of God which is at the center of Christianity; it also presumes to set aside the Decalogue which is given us by the living God and from which morality itself derives. What really is meant by a new moral code? Would it justify widespread practices that are now in conflict with biblical ethics? Or would “a new code” accommodate itself to the revolt against the standards that our people, despite their failure to live up to them, have always accepted? No one, however well meaning, can set aside God’s laws, which do not change whether men keep them or not.

No, diagnosis of the sag in morality is not enough. Like every other problem that results from human sin, the moral problem cannot be solved merely on human, relativistic grounds. We need to acknowledge not only our failure but also our inability to cope with our failure apart from God’s continuing help. We need not a new moral code but a return to the divine law of Him who never changes. For recovery from the moral slump even to begin, we need to repent in accord with the Lord’s words to Solomon: “If my people, which are called by my name, shall humble themselves, and pray, and seek my face, and turn from their wicked ways; then will I hear from heaven, and will forgive their sin, and will heal their land.”

Gains In Evangelical Education

The steady gains registered by evangelical colleges across the land attest conservative Christianity’s growing stake in the liberal arts field.

Recently Spring Arbor College in Michigan, founded ninety years ago by Free Methodists, expanded from a junior college to a four-year liberal arts program with advance accreditation from the North Central Association. In a “miracle year,” President David L. McKenna announced projection and completion through gifts and private support of a new library and women’s dormitory, and an enrollment increase of 100.

Michigan’s Governor Romney, featured speaker for the inaugural program, noted that Michigan has a relatively small percentage of church-related higher educational institutions (fewer than twenty). Governor Romney expressed firm belief that America’s greatest danger is not subversion from without but submersion from within. He listed as present dangers:

“First of all, the submersion of individuality under the mass of giant corporations, giant educational institutions, and giant government.

“Secondly, the submersion of inherited principles of morality under the overwhelming pressure of conformity to the mores of the crowd.

“And finally, the submersion of idealism under the oppressive weight of pragmatism, of accommodation to the facts of life, or reality, if you prefer.…

“I firmly believe that this moral decay constitutes a greater danger to our country than the atomic bomb, or than the ambitious designs of the communists. If our country perishes it will crumble from within—not from the pressures which fall upon it from without.”

The governor indicated two roles that private Christian colleges can fulfill—to function as centers of education, and to function as “reservoirs of morality in a wasteland of decay.” He noted that church-related colleges have no monopoly on morality, since “the great moral teachings which comprise our Judeo-Christian heritage are available in abundance in our public institutions. But where the public institutions introduce the students to these principles of morality, the church-related institutions go a step further—they encourage the romance.”

Herbert Spencer long ago emphasized the tragedy of possessing knowledge and power without character. He declared that to educate reason without changing desire is to place a high-power gun in the hands of a savage. Free Methodist Bishop Leslie Marston has remarked that, were Spencer alive today, “he would substitute an H-bomb for a gun,” so immeasurably greater in this twentieth century is man’s power to destroy than it was in the nineteenth century.

In greetings to Spring Arbor College, Dr. Marston added some well-worded observations on the plight of contemporary education:

“We must admit that an education is inadequate and even dangerous to society, however great may be the learning and skill it produces, if it fails to achieve a culture of the heart and the development of a character to direct both learning and skill to the welfare of man and to the glory of God. We must have the safeguard of an education that is Christian.…

“But there are those who conceive of Christian education merely as an additive to secular education, missing the fact that to be Christian, education must be Christian to the core and not merely on the periphery. Christian education is not something less than education, with religion added; nor is it education, plus something other than education. Properly speaking, Christian education is the integration of all knowledge, life, and character in terms of those eternal principles of truth without which any education is deficient.”

These are sound principles. One may take heart that the evangelical community is determined to preserve the Christian stake in the liberal arts, and is determined also not to yield the educational enterprise to any narrow pursuit of unrelated facts indifferent to the claims of goodness and wisdom.

Protestant Conscience On Race Issues

There is much self-basting these days over discrimination against minority groups, and it is well so. Never as now has emphasis been needed on the equal dignity of all men before the law.

Some spokesmen, however, are using the occasion not so much to pummel their own consciences as to malign others. The Church in general is blamed for all the evils of this world. Or the South’s racial problems are traced by liberal spokesmen to “arthritic evangelicalism.”

There is no reason to deny evangelicals a full measure of blame in many matters. But when liberal scholars refer to “arthritic” evangelicalism—as if that designation exhausted all available varieties—either these critics have become propagandists or they simply are not informed.

Not all evangelicalism is concerned merely about pious peccadilloes. True as it is that biblical beliefs need to be fully worked out on the subject of race, let us remember that evangelicals sponsored those great missionary movements to Africa and Asia. Let us remember that Finney’s revival crusade was anti-slavery. Let us remember that Billy Graham, long before many others from the South, took a strong stand on the race issue.

Despite all the liberal thunder on the subject of race today, let us remember too that there has been a great deal of “arthritic” liberalism also. In the 1820s, when Unitarianism in the Southland began its shift from biblical theology to social action, it almost died a-borning. For all the social-gospel emphasis (which had weaknesses of its own), the liberal conscience in the South awakened tardily to race issues, faced as it was by the magnitude of local problems. There is no need to single out evangelicals as an exclusive target of criticism, for foot-dragging on vital social issues is to be found in the entire spectrum of church and national life. And the aberrant liberal emphasis on legislative rather than regenerative solutions often tends to exchange one form of social injustice for another.

All of us share the guilt. No single theological emphasis can be credited with the movement for renewal. Serious differences exist as to whether CORE or NAACP or some other secular agency ought to define ecclesiastical strategy, or what reliance ought to be placed on this or that dynamism. But all agree that race prejudice is wicked, that all racial injustices must be overcome, and that an active program for transcending such injustices is necessary.

It is good, moreover, to find evangelicals reflecting the sensitive conscience on racial concerns discoverable in this issue’s essay on “Evangelicals and the Race Revolution.” Its author writes with the white heat of deep conviction. We need not agree—and, in fact, we do not—that Christians who were unenthusiastic about the “March on Washington” have forfeited their right to a voice in working out a solution. We know too many level-headed Christians who have had and will continue to have great influence in working out solutions but who remain convinced that street demonstrations may hasten changes while deferring the basic solution of the race problem.

The Billy Sunday Centennial

November 19, 1963, marks the centennial of the birth at Ames, Iowa, of William Ashley (Billy) Sunday, who through his revivals in the first decades of this century wrote an important chapter in the history of American evangelism. Those who heard him and his song leader, Homer Rodeheaver, in hundreds of revivals throughout the country were estimated at 100 million. His was the day of huge, specially constructed tabernacles in large cities, and under his urgent and vivid preaching multitudes “hit the sawdust trail.”

Before his conversion Billy Sunday had been a big-league baseball player. There were those who criticized his colloquial and sometimes slangy sermons and who called him a sensationalist because of his gymnastics in preaching. But his meetings, which reached a high point in New York in 1917, reflected the mood of the day. Moreover, in his impassioned advocacy of prohibition, he spoke for a good deal of contemporary Protestant idealism. His influence in the United States was widespread, the evangelical churches supported him, and his ministry marked for many thousands the difference between spiritual life and death.

Since Billy Sunday’s revivals, mass evangelism has undergone changes. The larger part of his ministry was in the years between the early 1900s and America’s entry into the First World War to “make the world safe for democracy.” This was a period of optimism, with the idea of progress prominent in religious thought. But more recent decades with the Second World War, the cold war, and the threat of atomic destruction have pressed upon mass evangelism a new seriousness of expression in keeping with an apocalyptic age. Present-day evangelism in its greatly expanded outreach through radio, television, and jet-age travel, has also developed organizationally in respect to public accounting of funds, cooperation with churches, and follow-up of inquirers.

Billy Sunday was a dedicated servant of Christ. God used him to speak to people of his day. His place in evangelism is secure, and there still live many who were won to Christ through him. He is not and will not be forgotten.

The Missing Step

Bishop Fred Pierce Corson, president of the World Methodist Council, recently proposed six “steps” that might lead to union between Protestantism and Roman Catholicism: communication, fellowship, education, communion, purpose, and effort. The proposal was made at the fall commencement of St. Joseph’s College in Philadelphia, at which Dr. Corson became the first Methodist bishop ever to receive an honorary degree from a Roman Catholic institution.

The bishop is a respected Protestant leader and a man of good will. Yet we wish that the steps he proposed had been seven in number, the seventh being doctrine, which, despite its educational implications must stand alone in its own right. For it is with doctrine that all efforts at church union must ultimately wrestle. The differences between Protestantism and Rome go very much deeper than communication, fellowship, education, communion, purpose, and effort. These may lead toward unity, but unity without agreement on the great biblical doctrines of the faith can lead only to compromise of precious conviction. For example, the doctrinal differences involved in the Roman Catholic mass as contrasted with varying Protestant positions regarding the Lord’s Supper represent deepest conviction and go to the heart of the separation between the two groups.

There is no question of Rome’s doctrinal position. In his homily at the opening of the second session of Vatican Council II, Pope Paul VI spoke of “those who believe in Christ but whom we have not the happiness of numbering amongst ourselves in the perfect unity of Christ, which only the Catholic Church can offer them.” He also declared that “this mystic and visible union cannot be attained save in identity of faith.…” Where Roman Catholicism stands doctrinally is clear and unambiguous. But the same firmness of doctrinal conviction is not characteristic of Protestant ecumenical leadership.

The present ecumenical exploration of union may be occupying itself with outward differences while hopefully underestimating the profound depths of doctrine that separate the great groups in Christendom. For if outward differences are sometime, somehow, reconciled, there will yet remain the great gulf of doctrine to be bridged.

But doctrine may not after all be a “step” to union. Instead it may well be the door to any true unity among Christians.

Elizabeth The Conqueror

London has a new possessor, and all America is indebted to the Columbia Broadcasting System for revealing this in a sabbath-evening telecast, “Elizabeth Taylor’s London.” London’s powers of survival heretofore have been enormous: The Londinium survived Boadicea’s sacking in A.D. 61; another layer of burnt ashes was added by a later fire during the Roman occupation; then there was the Great Fire of 1666; and only yesterday there was the devastating, measureless pounding of World War II. And now the great city had to draw itself up once more to face Elizabeth the Conqueror, in whose very presence even weak men were known to become weaker.

Would the woman whose powers had left children fatherless manage to disarm a city by her beauty? Would London’s friendly hospitality prove its downfall? It had to withstand the challenge of the hardened beauty of the face that stares at one continually from innumerable newsstands. The city confronted the flat, hard tones of an almost expressionless voice reading from the incomparable writings of Shakespeare, Wordsworth, Churchill, and from great speeches of Queen Elizabeth I and William Pitt.

This was the tour guide approved for Americans by some network executive, perhaps not entirely insensitive to commercial pressures which have been referred to by retarded souls as “callous.” It was Miss Taylor who was chosen to point to the Houses of Parliament, mother of parliaments, reflecting the grandeur of representative democracy. She showed us Big Ben, symbol of faithfulness through the years. We saw St. Paul’s and other great churches, reminders of moral uprightness. A clergyman graced the screen for a few moments to speak of the Pilgrims, now often dismissed as “Puritans.” The changing of the guard spoke of the courage and fortitude of the British fighting man. A reference to Lincoln’s Inn mirrored the majestic justice of British law. And there was the rugged strength of the Tower of London, the character of the Tower Bridge.

This was Liz Taylor’s London? But then there was also reference to Chelsea’s Bohemian life and a flickering reminder of the Dorchester Hotel, where Miss Taylor meets Mr. Burton. And in a climactic crescendo, Miss Taylor read a passage from Elizabeth Barrett Browning which spoke of the purity of love.

Selling Wheat To Russia

The government’s decision to permit the sale of American wheat to Communist Russia is so complex a moral and political question as to be deceptive.

Economically the decision seems sound enough. It will diminish our almost one-billion-bushel surplus, save the American taxpayer storage costs, and produce gold earnings to lessen our dollar drain. And in any event, Russia now gets our wheat or flour by the simple device of buying it from countries to which we sell it.

Yet both politically and morally the whole matter is highly ambiguous. Khrushchev has promised to bury us with the shovel of economic competition. If the weapons of his warfare are economic, is it wise to alleviate his economic troubles? Is not this like oiling your enemy’s gun?

On the other hand, a refusal to sell excess wheat to a hungry nation would not enhance the stature of the United States. Moreover, the sale is a dramatic spotlight showing all the world a basic weakness in the Communist society. Agriculture is the foundation of any nation’s economy. The sale of bread to a nation that may soon deliver a man to the moon but cannot deliver bread to his fellow men on earth is powerful propaganda. The sale may make the Soviet Union look not only hungry but also naked.

The President has assured Americans that the Russian people will learn where their bread comes from. They should. We also hope that they will learn that millions of Americans still pray, each day, “Give us this day our daily bread”; that many of them prayed over this wheat at springtime sowing and gave thanks to God in Thanksgiving Day prayers at harvest time.

The whole question is tangled in moral and political ambiguities. Should the United States sell, let alone give wheat to enemies that hunger? About a year ago Secretary Dean Rusk justified a “no wheat policy” for Red China, where there is massive hunger and starvation, on the ground that this was no time to lighten the pressures upon an unfriendly regime. Should we now offer free food to Cuba amidst its devastation by hurricane and thereby disprove the Castro propaganda that we hate the Cuban people?

It would seem that any wheat deal with Russia ought to have included as a condition the granting of some degree of freedom to peoples under Russian domination. Had Russia refused, Khrushchev would have shown the world that he would rather have people hungry than free. The mere fact that the sale is economically of mutual advantage is politically deceptive. Such relief as we shall get from too much wheat and too little gold is not equal to the political advantage the Soviets reap by relieving their hungry. The sale to Russia is more likely to be a straw in the wind than an isolated transaction. Trading our wheat for the freedom of others is a worthy consideration.