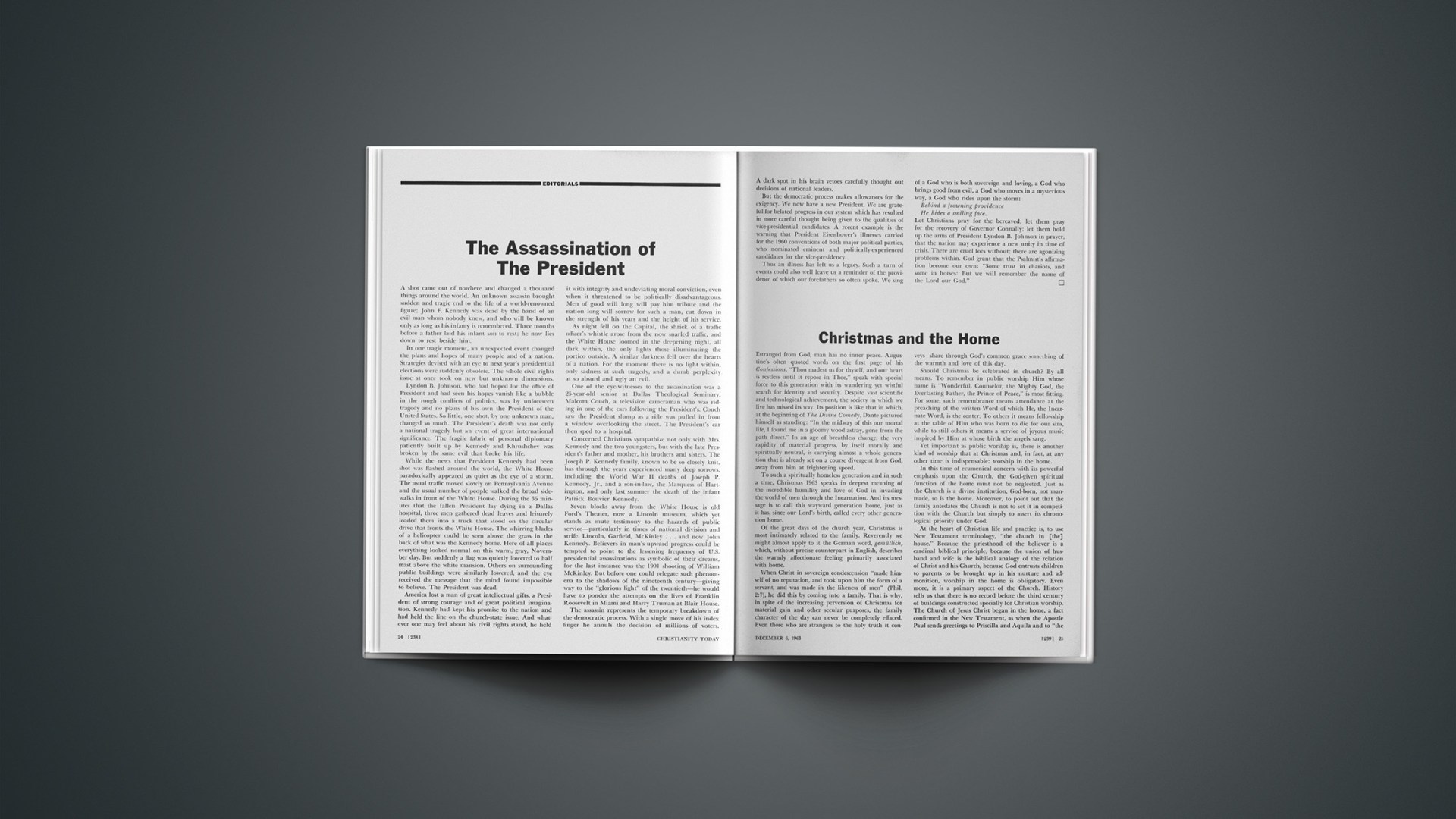

A shot came out of nowhere and changed a thousand things around the world. An unknown assassin brought sudden and tragic end to the life of a world-renowned figure; John F. Kennedy was dead by the hand of an evil man whom nobody knew, and who will be known only as long as his infamy is remembered. Three months before a father laid his infant son to rest; he now lies down to rest beside him.

In one tragic moment, an unexpected event changed the plans and hopes of many people and of a nation. Strategies devised with an eye to next year’s presidential elections were suddenly obsolete. The whole civil rights issue at once took on new but unknown dimensions.

Lyndon B. Johnson, who had hoped for the office of President and had seen his hopes vanish like a bubble in the rough Conflicts of politics, was by unforeseen tragedy and no plans of his own the President of the United States. So little, one shot, by one unknown man, changed so much. The President’s death was not only a national tragedy but an event of great international significance. The fragile fabric of personal diplomacy patiently built up by Kennedy and Khrushchev was broken by the same evil that broke his life.

While the news that President Kennedy had been shot was flashed around the world, the White House paradoxically appeared as quiet as the eye of a storm. The usual traffic moved slowly on Pennsylvania Avenue and the usual number of people walked the broad sidewalks in front of the White House.

During the 35 minutes that the fallen President lay dying in a Dallas hospital, three men gathered dead leaves and leisurely loaded them into a truck that stood on the circular drive that fronts the White House. The whirring blades of a helicopter could be seen above the grass in the back of what was the Kennedy home. Here of all places everything looked normal on this warm, gray, November day.

But suddenly a flag was quietly lowered to half mast above the white mansion. Others on surrounding public buildings were similarly lowered, and the eye received the message that the mind found impossible to believe. The President was dead.

America lost a man of great intellectual gifts, a President of strong courage and of great political imagination. Kennedy had kept his promise to the nation and had held the line on the church-state issue. And whatever one may feel about his civil rights stand, he held it with integrity and undeviating moral conviction, even when it threatened to be politically disadvantageous. Men of good will long will pay him tribute and the nation long will sorrow for such a man, cut down in the strength of his years and the height of his service.

As night fell on the Capital, the shriek of a traffic officer’s whistle arose from the now snarled traffic, and the White House loomed in the deepening night, all dark within, the only lights those illuminating the portico outside. A similar darkness fell over the hearts of a nation. For the moment there is no light within, only sadness at such tragedy, and a dumb perplexity at so absurd and ugly an evil.

One of the eye-witnesses to the assassination was a 25-year-old senior at Dallas Theological Seminary, Malcom Couch, a television cameraman who was riding in one of the cars following the President’s. Couch saw the President slump as a rifle was pulled in from a window overlooking the street. The President’s car then sped to a hospital.

Concerned Christians sympathize not only with Mrs. Kennedy and the two youngsters, but with the late President’s father and mother, his brothers and sisters. The Joseph P. Kennedy family, known to be so closely knit, has through the years experienced many deep sorrows, including the World War II deaths of Joseph P. Kennedy, Jr., and a son-in-law, the Marquess of Hartington, and only last summer the death of the infant Patrick Bouvier Kennedy.

Seven blocks away from the White House is old Ford’s Theater, now a Lincoln museum, which yet stands as mute testimony to the hazards of public service—particularly in times of national division and strife. Lincoln, Garfield, McKinley … and now John Kennedy. Believers in man’s upward progress could be tempted to point to the lessening frequency of U.S. presidential assassinations as symbolic of their dreams, for the last instance was the 1901 shooting of William McKinley. But before one could relegate such phenomena to the shadows of the nineteenth century—giving way to the “glorious light” of the twentieth—he would have to ponder the attempts on the lives of Franklin Roosevelt in Miami and Harry Truman at Blair House.

The assassin represents the temporary breakdown of the democratic process. With a single move of his index finger he annuls the decision of millions of voters. A dark spot in his brain vetoes carefully thought out decisions of national leaders.

But the democratic process makes allowances for the exigency. We now have a new President. We are grateful for belated progress in our system which has resulted in more careful thought being given to the qualities of vice-presidential candidates. A recent example is the warning that President Eisenhower’s illnesses carried for the 1960 conventions of both major political parties, who nominated eminent and politically-experienced candidates for the vice-presidency.

Thus an illness has left us a legacy. Such a turn of events could also well leave us a reminder of the providence of which our forefathers so often spoke. We sing of a God who is both sovereign and loving, a God who brings good from evil, a God who moves in a mysterious way, a God who rides upon the storm:

Behind a frowning providence

He hides a smiling face.

Let Christians pray for the bereaved; let them pray for the recovery of Governor Connally; let them hold up the arms of President Lyndon B. Johnson in prayer, that the nation may experience a new unity in time of crisis. There are cruel foes without; there are agonizing problems within. God grant that the Psalmist’s affirmation become our own: “Some trust in chariots, and some in horses: But we will remember the name of the Lord our God.”