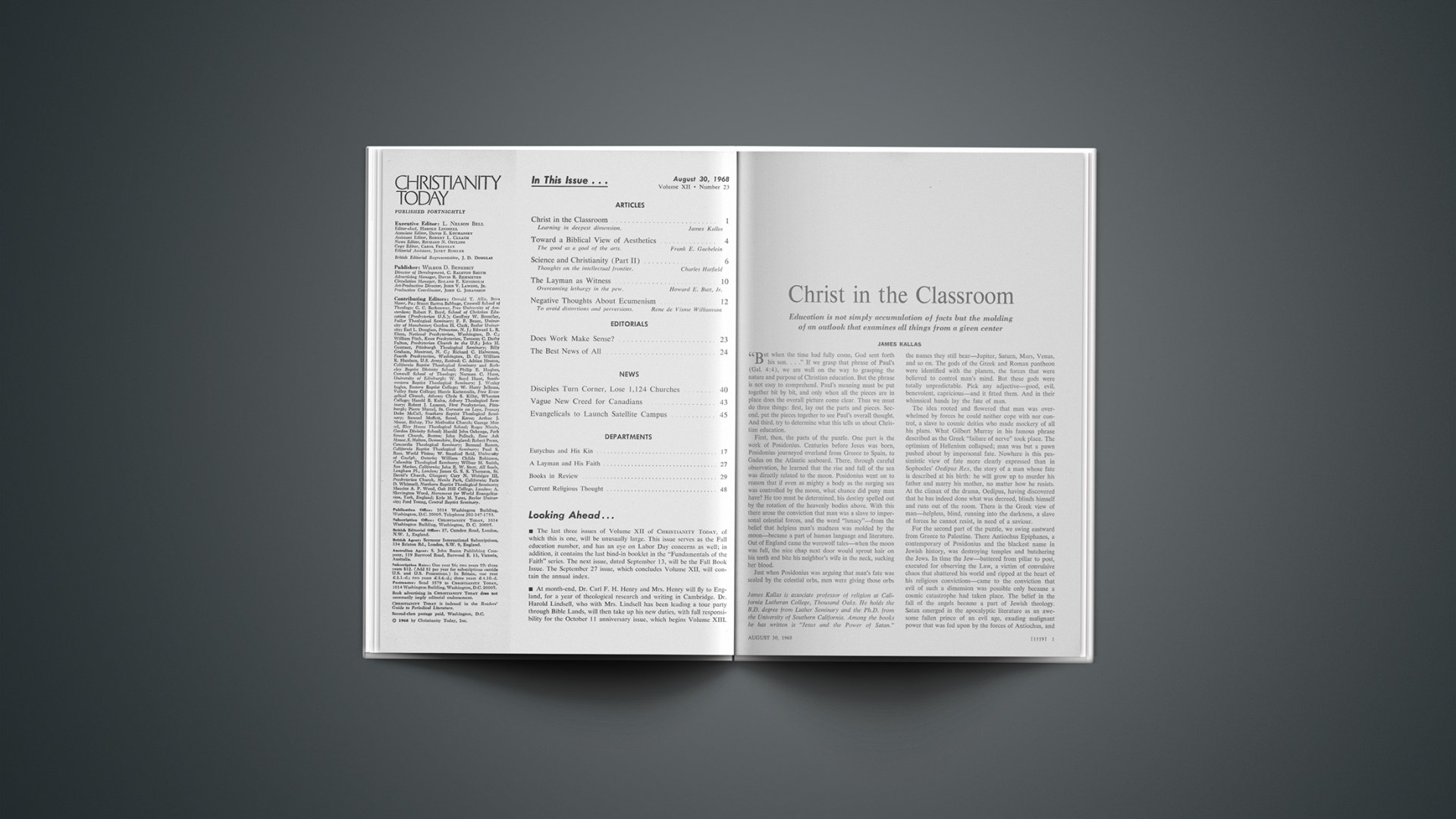

Education is not simply accumulation of facts but the molding of an outlook that examines all things from a given center

“But when the time had fully come, God sent forth his son.…” If we grasp that phrase of Paul’s (Gal. 4:4), we are well on the way to grasping the nature and purpose of Christian education. But the phrase is not easy to comprehend. Paul’s meaning must be put together bit by bit, and only when all the pieces are in place does the overall picture come clear. Thus we must do three things: first, lay out the parts and pieces. Second, put the pieces together to see Paul’s overall thought. And third, try to determine what this tells us about Christian education.

First, then, the parts of the puzzle. One part is the work of Posidonius. Centuries before Jesus was born, Posidonius journeyed overland from Greece to Spain, to Gades on the Atlantic seaboard. There, through careful observation, he learned that the rise and fall of the sea was directly related to the moon. Posidonius went on to reason that if even as mighty a body as the surging sea was controlled by the moon, what chance did puny man have? He too must be determined, his destiny spelled out by the rotation of the heavenly bodies above. With this there arose the conviction that man was a slave to impersonal celestial forces, and the word “lunacy”—from the belief that helpless man’s madness was molded by the moon—became a part of human language and literature. Out of England came the werewolf tales—when the moon was full, the nice chap next door would sprout hair on his teeth and bite his neighbor’s wife in the neck, sucking her blood.

Just when Posidonius was arguing that man’s fate was sealed by the celestial orbs, men were giving those orbs the names they still bear—Jupiter, Saturn, Mars, Venus, and so on. The gods of the Greek and Roman pantheon were identified with the planets, the forces that were believed to control man’s mind. But these gods were totally unpredictable. Pick any adjective—good, evil, benevolent, capricious—and it fitted them. And in their whimsical hands lay the fate of man.

The idea rooted and flowered that man was overwhelmed by forces he could neither cope with nor control, a slave to cosmic deities who made mockery of all his plans. What Gilbert Murray in his famous phrase described as the Greek “failure of nerve” took place. The optimism of Hellenism collapsed; man was but a pawn pushed about by impersonal fate. Nowhere is this pessimistic view of fate more clearly expressed than in Sophocles’ Oedipus Rex, the story of a man whose fate is described at his birth: he will grow up to murder his father and marry his mother, no matter how he resists. At the climax of the drama, Oedipus, having discovered that he has indeed done what was decreed, blinds himself and runs out of the room. There is the Greek view of man—helpless, blind, running into the darkness, a slave of forces he cannot resist, in need of a saviour.

For the second part of the puzzle, we swing eastward from Greece to Palestine. There Antiochus Epiphanes, a contemporary of Posidonius and the blackest name in Jewish history, was destroying temples and butchering the Jews. In time the Jew—battered from pillar to post, executed for observing the Law, a victim of convulsive chaos that shattered his world and ripped at the heart of his religious convictions—came to the conviction that evil of such a dimension was possible only because a cosmic catastrophe had taken place. The belief in the fall of the angels became a part of Jewish theology. Satan emerged in the apocalyptic literature as an awesome fallen prince of an evil age, exuding malignant power that was fed upon by the forces of Antiochus, and the whole world lay in the power of the evil one. Man was a slave, helpless, blind, running into the darkness, overwhelmed by evil forces he could not resist, in need of a saviour.

This is the second part of the puzzle, and we now can see Paul’s thought taking shape. Different as the Graeco-Roman tradition and Judaism were in many ways, here they were united. Both agreed that man was in need of a saviour. This, then, lies behind Paul’s assertion. “When the time had fully come,” when the minds of men were ready, when the world stage was psychologically set, when men had come to see their need of a saviour—at that moment “God sent forth his son.”

But the stage of the world was also set geographically or historically. That is the third part of the puzzle. For seven hundred years before Jesus was born, an enormous writhing had been taking place, as one world empire after another was raised up only to fall. Assyria emerged as a colossus and swallowed up all the little lands and tribes around her. But Assyria fell, consumed by Babylon. Then Babylon fell to Persia, and then Persia to Greece when Alexander strode out of the Macedonian mountains to conquer the world before he was thirty. With each new empire the frontiers were pushed further. Alexander’s rule reached across three continents, but even then the crest had not been reached. Greece fell to Rome, and under the great grey eagles of the Roman legions lay the whole known world, from the fog-shrouded moorlands of northern England to the sunny sands of Africa and all the way to the fabled cities of the Orient. The Pax Romana prevailed. For the first and only time in all of human history there was one world, one government, one language. Travel was fluid along the great Roman roads, for there were no robbers to fear, no borders to cross, no money to exchange. For the first and only time in all of human history a wandering evangelist could go where he would, preaching to all he met in one universal language.

FROM GALILEE TO MOUNT OLIVE

And standing by the wet salt

No fish spoke,

No clouds knocked.

No—all sat and knelt and stood

Inside the bubble of Heaven

Now there.

Then came men—

Who had been already Waiting

For the breaking

And the dogmatic spilling

Of it—

Of Him.

But they waited worlds

Without end swimming,

Fishing,

And suffering

Into a bubble

Unbreaking.

From the weakest

The great came

And another

Relieving.

Of the breaking

Emerged a solid.

ALBERT SCOFIELD KNORR

All this lies buried in Paul’s cryptic statement, “When the time had fully come, God sent forth his son.” He is making the staggering claim that the rise and fall of nations was no accident. God had been active in all this, setting the stage of the world for the birth of the Saviour. History was “his story.” Psychologically, spiritually, geographically, historically, the time had come. The world was unified in such a way that one like Paul could walk the Mediterranean basin preaching to all he met. Both halves of the ancient world—Jews and Greeks—knew their need of a saviour. At that point in history Christ was born.

This is the powerful context of Paul’s assertion. Surveying the sweep of centuries, he sees in all that has gone before the hand of God, preparing the world for the proclamation and reception of salvation in Christ’s name.

But all this, someone may say, is only interpretation, a Christian reconstruction of independent and unrelated facts. And besides, what does it have to do with Christian education?

What I am saying is that every area of academic life, in one way or another, is ultimately saturated with religious thought. Look at the ground we have fleetingly covered. We spoke of philosophy, Posidonius; of literature, the werewolves and Oedipus Rex; of geography, history, and anthropology, the rise of Rome and the emergency of Western civilization—of almost every area represented in the ordinary college catalog. Each of these is essentially a religious area and ought to be tied to the proclamation of Christ.

Of course what I have done is to interpret. Nowhere does Sophocles say that he wrote Oedipus Rex in order to depict the despair of the Greeks and thus pave the way for the coming saviour. Nowhere in the mad rantings of Antiochus will you find him saying that he persecuted the Jew simply to show him his bondage to the devil and his need for release through Christ. Nowhere do we find a Julius or an Augustus explaining that he wanted to weld the world together in order to enhance the ministry of itinerant Christian evangelists. To deny that my view is an interpretation, a Christian conviction I insist on placing on certain facts, would be ludicrous.

But that is precisely what education is: interpretation, the impartation of a point of view, the modeling and molding of an outlook that examines all things from a given center. Education is not simply the accumulation of random facts and figures and dates. Knowing when Frederick Barbarossa died, or how many mistresses Louis Quatorze had, might win you a TV set on a quiz program, but it will not qualify you as an educated person. Education in the deepest sense is the formation of a perspective, the building up of a position, the development of an outlook from which all life’s problems are analyzed and evaluated. Education is a creation of a sense of values, the establishment of priorities. The truly educated man is an integrated man. He has a comprehensive, single-minded view that includes all of reality (an insight known to those who first named a center of higher learning a “university” after the vastest thing they knew, the universe—a far cry from the muddleheaded pedagogues who today speak of a “multiversity,” as if learning could be chopped into pieces like a salami).

Christian education is the impartation of a point of view that puts Christ at that vital integrative center, that insists it is with him as Alpha and Omega that all human history and knowledge is to be comprehended. Christian education is indoctrination. It is a deliberate attempt to cultivate the conviction that it is not only proper and legitimate but also vitally necessary to see all things from the vantage point of the Cross.

Many within the Church and most outside it consider “indoctrination” a dirty word, one that has no place in educational circles. In a way, the Church may have brought this on itself. There has been and still is an abuse of the principle of Christian education, a substitution of piety for intellectual effort, of close-minded indoctrination for courageous examination of the facts. In this system, one who can write “I love Jesus” in a nicely flowing hand gets “A” for English. But an abuse of indoctrination cannot be allowed to force the pendulum to the other extreme—to cause us to forget that education is education only when it creates a sense of values, when it takes a stand, argues for commitment, zealously proclaims a position.

We live in a pedagogical age of permissiveness and openendedness. The professor should never take a stand, we are told; to assume a position and argue for a conviction is authoritarian and medieval, a form of totalitarian brainwashing. The professor is simply to present the facts, all the competing theories, and to argue for none. Let the student make his own choice. Allow the competing philosophies of life to gallop freely and the best will win.

But this is absurd. A true ideology will not necessarily win the race. A false one can sweep over a whole nation—think of Hitler, or of today’s Communism. Education is not some mechanical process in which the student is simply exposed to a raw bundle of facts and miraculously comes out, on his own, with all the right insights. He needs guidance and direction, he needs professors who profess, who take a stand. A neutral, non-professing professor impoverishes education and betrays his calling.

Even if neutrality were desirable, it would still be unattainable. To take no stand at all is a stand. It is not neutrality but relativism, a denial of absolutes. And it is as doctrinaire as any deliberately Christian stance.

All education—not just education on the Christian campus—is indoctrination. Those who would argue that education is to be free-swinging and open, with no commitment to any cause, simply do not know what education is. For every institution, every area of academic life, begins with its givens, its assumptions, its unargued absolutes, things taken as truths beyond all debate. In political-science courses and in law schools, the student is not given the luxury of deciding whether the Constitution is valid or not; he simply assumes it is. From this absolute he moves on into his studies. In science courses, we do not ask the student whether he accepts the scientific method of observation, measurement, and evaluation as valid; we simply assume its validity and ingrain that assumption into him.

Christian education rests on the conviction that every area of academic endeavor must be tied to the Cross, related to that event that split apart human history. Approximately nineteen hundred seventy years ago Jesus was born, and his life and death are the center of all time. That conviction undergirds, establishes, and informs all that we say and teach.

Certainly it makes a difference to the work of the psychologist whether he is Christian or not. Is man a self-contained entity not open to the interference of supernatural powers, determined only by heredity and environment? Or is he open to grace, influenced by the Holy Spirit, able to be renewed by spiritual forces outside himself? A man’s religion, his Christian conviction or lack of it, cannot be shut out of his teaching of psychology and the nature of man.

Christian education is the conviction that all academic endeavor must be so related to the Christian proclamation. It is the insistence that behind ordered chemical equations and mathematical formulas we see the hand of God, who is able to bring design and beauty out of primeval chaos. It is the insistence that though philosophers can wrestle forever with the great and enduring questions of what is man and what is life, only when men look at the Cross are those questions answered. For in the Cross we see the truth of man’s depravity, that he will crucify the good. We see also that, even as we throw Christ’s hands apart to crucify him, he spreads his arms to forgive us; and in that is man’s worth. In history we insist that life is not chaotic, without purpose or meaning. And great literature is great because it speaks of man’s desire to be more than an animal—an aspiration affirmed in the first book of the Bible, which says that man is made in the image of God.

This is the purpose of Christian education, to show that Christ is the center of all learning and pervades every moment of life, giving answer to man’s cry for meaning.

Milton D. Hunnex is professor and head of the department of philosophy at Willamette University, Salem, Oregon. He received the B.A. and M.A. degrees from the University of Redlands and the Ph.D. in the Inter-collegiate Program in Graduate Studies, Claremont, California. He is author of “Philosophies and Philosophers.”