Athletes And Faith

The Tommy John Story, by Tommy and Sally John (Revell, 1979, 175 pp., $6.95); Safe at Home, by Richard Arndt (Concordia, 1979, 120 pp., $3.95); Second Wind, by Bill Russell and Branch Taylor (Random House, 1979, 264 pp., $9.95); No Easy Game, by Terry Bradshaw (Revell, 1979, 165 pp. $3.95); Terry Bradshaw: Man of Steel, by Terry Bradshaw (Zondervan, 1979, 195pp., $7.95); Jesse, by Jesse Owens (Logos, 1979, 205 pp., $6.95); are reviewed by Larry Winterholter, head of Department of Physical Education, Health and Athletics, Taylor University, Upland, Indiana.

Interest in sports in the United States has never been higher as evidenced by the detailed coverage of sporting events and personalities in the news media. This is especially true in this 1980 Olympic year.

Safe At Home, by Richard Arndt, is a book in which 10 Christian major league baseball players share what Christ means to them and how being a Christian fits into a baseball career. Men such as Pat Kelly of the Baltimore Orioles, Don Kessinger, former Chicago Cub and White Sox player and manager, and Don Sutton, Los Angeles Dodger pitcher, share the high points in their careers and frequently how they have grown as Christians. The book is an excellent inspirational book for the young baseball fan. However, the level of sharing and numerous quotes will make it difficult reading for the Little Leaguer.

Recent success for Terry Bradshaw, quarterback of the Pittsburgh Steelers, has heightened public interest in his background and personality. It is quite interesting that his career has not always prospered and this facet of his life is described well in No Easy Game and Terry Bradshaw: Man of Steel. Both books are light and entertaining for the football fan, but do reveal some of the frustrations and struggles that are related to the life of glitter. Terry’s ego appears occasionally in relating incidents, but a disarming personality is evident throughout along with a sincere desire to live the Christian life. Young and old both can enjoy the books; they will find No Easy Game a more detailed account of Bradshaw’s early life, and thus a logical first choice if both books are read.

The Tommy John Story is an account of the New York Yankee pitcher, formerly a pitcher for the Los Angeles Dodgers, who severely injured his pitching elbow in 1974. in the midst of what promised to be his best season. The book is an account of his rise in baseball to that point, and then a description of the long road to recovery he traveled, which lasted nearly two years and entailed numerous operations and frustrations. The reader again must deal with a degree of spiritual shallowness and self-centeredness, but the story nevertheless is inspirational and does illustrate the need and desire of an individual to grow spiritually when faced with trials. The reading is pleasant and readers of all ages should find the book enjoyable.

An extremely fascinating story for an Olympic year is Jesse, the Man Who Outran Hitler. 1936 found Adolph Hitler planning to demonstrate the superiority of the Aryan race, only to have the son of a black Alabama sharecropper come to Germany and shatter that plan. Jesse Owens shares the story of his life from those very humble beginnings in Alabama to the incredibly dramatic victories in Berlin, and the subsequent years of personal successes and failures. The book is captivating and easy to read. It seemed, however, to be sadly lacking in evidence of a real relationship with Christ. While Mr. Owens, who died in April, was obviously a tremendous person who overcame many obstacles in his lifetime, the book, though well done, leaves one the impression of self-accomplishment and self-will rather than submission and obedience to Christ—somewhat like reading a tragedy.

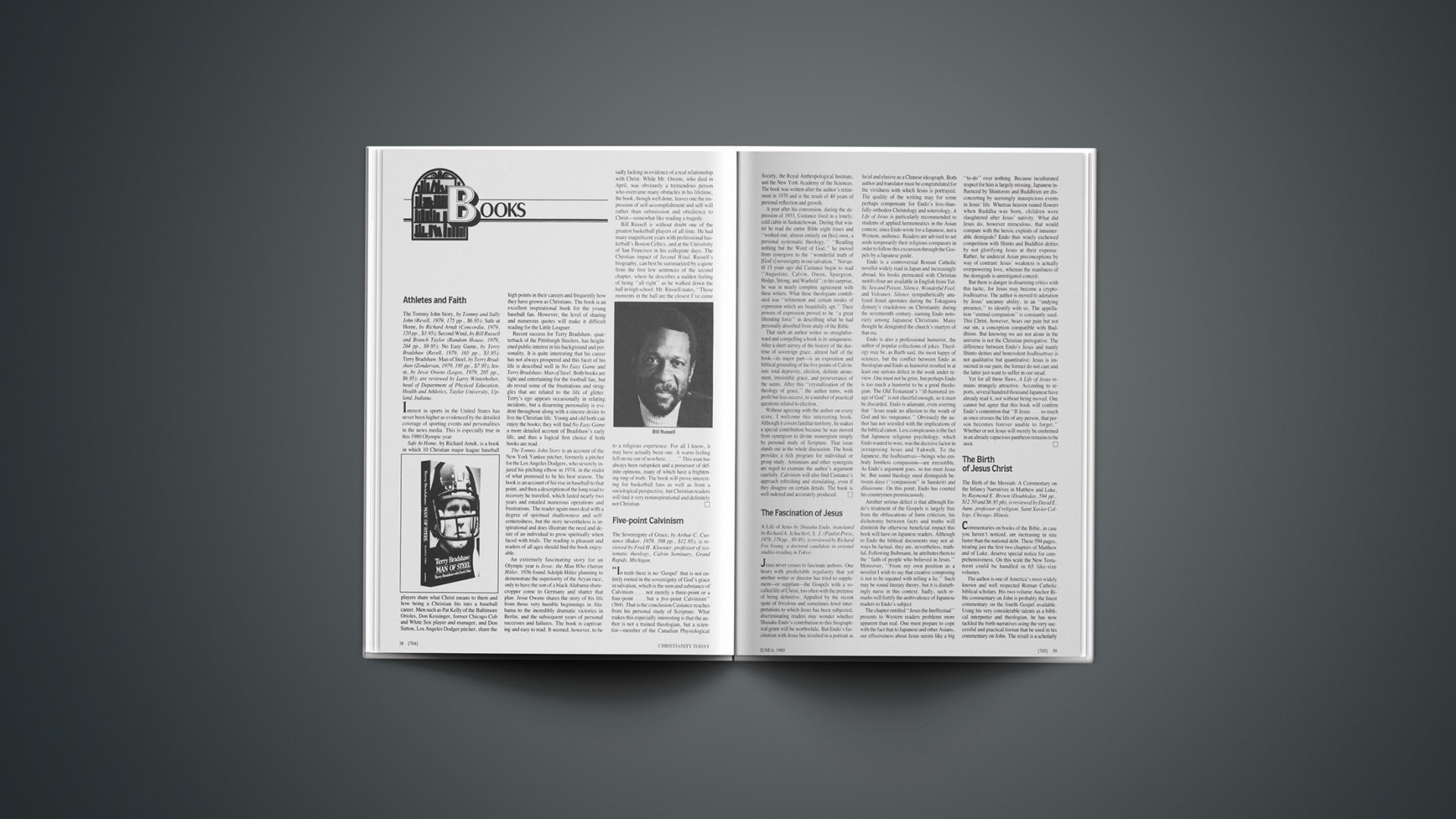

Bill Russell is without doubt one of the greatest basketball players of all time. He had many magnificent years with professional basketball’s Boston Celtics, and at the University of San Francisco in his collegiate days. The Christian impact of Second Wind, Russell’s biography, can best be summarized by a quote from the first few sentences of the second chapter, where he describes a sudden feeling of being “all right” as he walked down the hall in high school. Mr. Russell states, “Those moments in the hall are the closest I’ve come to a religious experience. For all I know, it may have actually been one. A warm feeling fell on me out of nowhere.…” This man has always been outspoken and a possessor of definite opinions, many of which have a frightening ring of truth. The book will prove interesting for basketball fans as well as from a sociological perspective, but Christian readers will find it very noninspirational and definitely not Christian.

Five-Point Calvinism

The Sovereignty of Grace, by Arthur C. Custance (Baker, 1979, 398 pp., $12.95), is reviewed by Fred H. Klooster, professor of systematic theology, Calvin Seminary, Grand Rapids, Michigan.

“In truth there is no ‘Gospel’ that is not entirely rooted in the sovereignty of God’s grace in salvation, which is the sum and substance of Calvinism … not merely a three-point or a four-point … but a five-point Calvinism” (364). That is the conclusion Custance reaches from his personal study of Scripture. What makes this especially interesting is that the author is not a trained theologian, but a scientist—member of the Canadian Physiological Society, the Royal Anthropological Institute, and the New York Academy of the Sciences. The book was written after the author’s retirement in 1970 and is the result of 40 years of personal reflection and growth.

A year after his conversion, during the depression of 1933, Custance lived in a lonely, cold cabin in Saskatchewan. During that winter he read the entire Bible eight times and “worked out, almost entirely on [his] own, a personal systematic theology.” “Reading nothing but the Word of God,” he moved from synergism to the “wonderful truth of [God’s] sovereignty in our salvation.” Not until 15 years ago did Custance begin to read “Augustine, Calvin, Owen, Spurgeon, Hodge, Strong, and Warfield”; to his surprise, he was in nearly complete agreement with these writers. What these theologians contributed was “refinement and certain modes of expression which are beautifully apt.” Their powers of expression proved to be “a great liberating force” in describing what he had personally absorbed from study of the Bible.

That such an author writes so straightforward and compelling a book is its uniqueness. After a short survey of the history of the doctrine of sovereign grace, almost half of the book—its major part—is an exposition and biblical grounding of the five points of Calvinism: total depravity, election, definite atonement, irresistible grace, and perseverance of the saints. After this “crystallization of the theology of grace,” the author turns, with profit but less success, to a number of practical questions related to election.

Without agreeing with the author on every score, I welcome this interesting book. Although it covers familiar territory, he makes a special contribution because he was moved from synergism to divine monergism simply by personal study of Scripture. That issue stands out in the whole discussion. The book provides a rich program for individual or group study. Arminians and other synergists are urged to examine the author’s argument carefully. Calvinists will also find Custance’s approach refreshing and stimulating, even if they disagree on certain details. The book is well indexed and accurately produced.

The Fascination Of Jesus

A Life of Jesus by Shusaku Endo, translated by Richard A. Schuchert, S. J. (Paulist Press, 1978. 179pp., $9.95), is reviewed by Richard Fox Young, a doctoral candidate in oriental studies residing in Tokyo.

Jesus never ceases to fascinate authors. One hears with predictable regularity that yet another writer or director has tried to supplement—or supplant—the Gospels with a so-called life of Christ, too often with the pretense of being definitive. Appalled by the recent spate of frivolous and sometimes lewd interpretations to which Jesus has been subjected, discriminating readers may wonder whether Shusaku Endo’s contribution to this biographical genre will be worthwhile. But Endo’s fascination with Jesus has resulted in a portrait as lucid and elusive as a Chinese ideograph. Both author and translator must be congratulated for the vividness with which Jesus is portrayed. The quality of the writing may for some perhaps compensate for Endo’s less-than-fully-orthodox Christology and soteriology. A Life of Jesus is particularly recommended to students of applied hermeneutics in the Asian context, since Endo wrote for a Japanese, not a Western, audience. Readers are advised to set aside temporarily their religious compasses in order to follow this excursion through the Gospels by a Japanese guide.

Endo is a controversial Roman Catholic novelist widely read in Japan and increasingly abroad, his books permeated with Christian motifs (four are available in English from Tuttle: Sea and Poison, Silence, Wonderful Fool, and Volcano). Silence sympathetically analyzed Jesuit apostates during the Tokugawa dynasty’s crackdown on Christianity during the seventeenth century, earning Endo notoriety among Japanese Christians. Many thought he denigrated the church’s martyrs of that era.

Endo is also a professional humorist, the author of popular collections of jokes. Theology may be, as Barth said, the most happy of sciences, but the conflict between Endo as theologian and Endo as humorist resulted in at least one serious defect in the work under review. One must not be grim, but perhaps Endo is too much a humorist to be a good theologian. The Old Testament’s “ill-humored image of God” is not cheerful enough, so it must be discarded. Endo is adamant, even averring that “Jesus made no allusion to the wrath of God and his vengeance.” Obviously the author has not wrestled with the implications of the biblical canon. Less conspicuous is the fact that Japanese religious psychology, which Endo wanted to woo, was the decisive factor in juxtaposing Jesus and Yahweh. To the Japanese, the bodhisattvas—beings who embody limitless compassion—are irresistible. As Endo’s argument goes, so too must Jesus be. But sound theology must distinguish between daya (“compassion” in Sanskrit) and dikaiosune. On this point, Endo has courted his countrymen promiscuously.

Another serious defect is that although Endo’s treatment of the Gospels is largely free from the obfuscations of form criticism, his dichotomy between facts and truths will diminish the otherwise beneficial impact this book will have on Japanese readers. Although to Endo the biblical documents may not always be factual, they are, nevertheless, truthful. Following Bultmann, he attributes them to the “faith of people who believed in Jesus.” Moreover, “From my own position as a novelist I wish to say that creative composing is not to be equated with telling a lie.” Such may be sound literary theory, but it is disturbingly naive in this context. Sadly, such remarks will fortify the ambivalence of Japanese readers to Endo’s subject.

The chapter entitled “Jesus the Ineffectual” presents to Western readers problems more apparent than real. One must prepare to cope with the fact that to Japanese and other Asians, our effusiveness about Jesus seems like a big “to-do” over nothing. Because inculturated respect for him is largely missing. Japanese influenced by Shintoism and Buddhism are disconcerting by seemingly inauspicious events in Jesus’ life. Whereas heaven rained flowers when Buddha was born, children were slaughtered after Jesus’ nativity. What did Jesus do, however miraculous, that would compare with the heroic exploits of innumerable demigods? Endo thus wisely eschewed competition with Shinto and Buddhist deities by not glorifying Jesus at their expense. Rather, he undercut Asian preconceptions by way of contrast: Jesus’ weakness is actually overpowering love, whereas the manliness of the demigods is unmitigated conceit.

But there is danger in disarming critics with this tactic, for Jesus may become a crypto-bodhisattva. The author is moved to adoration by Jesus’ uncanny ability, in an “undying presence,” to identify with us. The appellation “eternal companion” is constantly used. This Christ, however, bears our pain but not our sin, a conception compatible with Buddhism. But knowing we are not alone in the universe is not the Christian prerogative. The difference between Endo’s Jesus and manly Shinto deities and benevolent bodhisattvas is not qualitative but quantitative: Jesus is immersed in our pain; the former do not care and the latter just want to suffer in our stead.

Yet for all these flaws, A Life of Jesus remains strangely attractive. According to reports, several hundred thousand Japanese have already read it, not without being moved. One cannot but agree that this book will confirm Endo’s contention that “If Jesus … so much as once crosses the life of any person, that person becomes forever unable to forget.” Whether or not Jesus will merely be enshrined in an already capacious pantheon remains to be seen.

The Birth Of Jesus Christ

The Birth of the Messiah: A Commentary on the Infancy Narratives in Matthew and Luke, by Raymond E. Brown (Doubleday, 594 pp., $12.50 and $6.95 pb), is reviewed by David E. Aune, professor of religion, Saint Xavier College, Chicago, Illinois.

Commentaries on books of the Bible, in case you haven’t noticed, are increasing in size faster than the national debt. These 594 pages, treating just the first two chapters of Matthew and of Luke, deserve special notice for comprehensiveness. On this scale the New Testament could be handled in 65 like-size volumes.

The author is one of America’s most widely known and well respected Roman Catholic biblical scholars. His two-volume Anchor Bible commentary on John is probably the finest commentary on the fourth Gospel available. Using his very considerable talents as a biblical interpreter and theologian, he has now tackled the birth narratives using the very successful and practical format that he used in his commentary on John. The result is a scholarly book of the first magnitude. Aside from the very lengthy introductory sections, the text is broken down into relatively self-contained sections, each of which is treated in the following way: (1) a new translation of the text is presented, followed by (2) notes on exegetical and problematic details, often of a linguistic nature, which are printed in a fine print and designed to be skipped over by those interested in broader issues, followed by (3) comments on the text, and (4) an extensive bibliography on the section. Brown’s knowledge of secondary literature is astonishing and his control of the biblical text is exemplary. The commentary is lucidly written and the many exegetical and historical problems are faced clearly and honestly.

The birth narratives are very difficult for the commentator. Since J. G. Machen’s The Virgin Birth of Christ (1930) evangelical scholars have more or less neglected to reat them extensively. Evangelical laymen and pastors tend to think of the issues involved in the Gospel birth stories in terms of an either/or: Did the events narrated in Matthew 1 and 2 and Luke 1 and 2 happen or didn’t they? Those who deny their historicity are liberals, while thoe who affirm their historicity are conservatives.

The virgin birth, or more accurately, the virginal conception, of Jesus is the focal point of the Gospel birth narratives; however, many subordinate elements are also contained, such as the genealogies of Jesus, various accounts of divine and angelic revelations to the principals in the story, the coming of the Magi, Herod’s attempt to eliminate Jesus, the birth and naming of John the Baptist, the visitation of Mary to Elisabeth, the role of the shepherds, and Jesus’ appearance in the temple at the age of 12.

What does Brown think about the historicity of the virginal conception? In his view, “the scientifically controllable biblical evidence leaves the question of the historicity of the virginal conception unresolved” (p. 527). Brown is aware that this carefully worded judgment will probably shock the average believer asmuch as the critical biblical scholar.

In considering the birth narratives of Matthew and Luke, there is a natural tendency to compare (and contrast) them with one another. Brown suggests three possible views that the reader can take regarding the two accounts: (1) both may be historical, (2) one may be historical and the other much freer, or (3) both may represent nonhistorical dramatizations (p. 34). He clearly rejects the first two alternatives (p. 36), and he really does not espouse the third. His basic approach is that the birth narratives in both Gospels are primarily literary vehicles which the evangelists used to express their own theological views. At the same time the basic historicity of the events narrated is not given up.

Brown does not begin with a theory of inspiration to determine historicity, since he holds that a “divinely inspired story is not necessarily history” (p. 34). Brown’s treatment of the genealogies of Matthew 1:1–17 and Luke 3:23–38 exemplify his approach. Since the second century, Christians have puzzled over the problems presented by these genealogies; the basic problem, of course, is that they do not agree. How does Brown handle this complex issue? He shows that genealogies in the ancient near East rarely functioned to preserve strictly biological lineage. They do appear to have functioned in three primary ways: (1) to establish an individual’s identity in relationship to his tribe or clan, (2) to undergird the status of those holding or seeking important positions, and (3) to reflect one’s basic character, since in the ancient view descendants are like their forebears. The Matthaean genealogy functions, according to Brown, in the second of these three ways. The genealogies in Matthew and Luke, he claims, are not intended to give us certain information about Jesus’ grandparents and great grandparents, but to tell us theologically that he is the “son of David, son of Abraham” (Matthew), and the “Son of God” (Luke).

None will find themselves agreeing with each of the positions that Brown advocates on the many different issues involved in interpreting the birth narratives. His own stated objective, and one that he has met, is to provide the data and the framework for those sufficiently interested in the issues to make their own decisions, even though these decisions will be at variance with Brown’s own.

An Evangelical Heavyweight

God, Revelation and Authority, Volume IV, by Carl F. H. Henry (Word. 1979. 674 pp. $24.95), is reviewed by Ronald Nash, head, Department of Philosophy and Religion, Western Kentucky University, Bowling Green.

The continuation of Dr. Henry’s epochal “exposition of evangelical theism” concludes his study of 15 theses about divine revelation. Henry’s treatment of the doctrine of God is reserved for the fifth and final volume of the series, which should appear in about three years. With biblical authority and inerrancy as two of its major topics, volume four should attract a great deal of attention.

Because divine revelation is inscripturated in the Bible, Scripture is the authoritative norm of Christian truth today. The contemporary secular assault on biblical authority, Henry points out, is only another manifestation of modern man’s skepticism with regard to all authority. Since man is in revolt against God, it is only natural that he should repudiate all divine authority, including the Word of God. But when modern man rejects God as the ultimate source of all authority, a moral and intellectual vacuum is created that invites the entrance of powerful political ideologies. The contemporary secularist is not content to repudiate God’s authority. Worshiping at the shrine of human autonomy, he thinks that man “must originate and fashion whatever values there are.” Henry analyzes and criticizes the major contemporary reductions of biblical authority found in the writings of theologians like Paul Tillich, James Barr, and Schubert Ogden. Henry warns of the tendency of a growing number of professed evangelicals to reduce and restrict biblical authority. One manifestation of this evangelical reductionism is the writings of devotees of several currently popular causes who chafe because Scripture fails to support their positions. Instead of reexamining their own causes, they in effect lay down a series of conditions that God’s Word must satisfy if they are to accept its authority. Thus, when Scripture fails to advance what they take to be the “right view” on such issues as feminism or liberation theology or homosexuality, they simply reject or reduce the authority of Scripture, frequently on the ground that the literal sense of the Bible does not apply to the altered cultural setting of today.

Henry argues that all attempts to relieve the alleged burden of being a religion of the Book from Christianity are misdirected. “From the very first, the Christian religion involved a distinctive deposit of authoritative prophetic literature, confirmed as such even by the incarnate, crucified and risen Jesus, who pledged to designated apostles the operative presence of the Spirit of God in their exposition of his life and work.” The authority of Scripture is acknowledged even by those who repudiate it. Even those critical of the Bible appeal to it in support of some beliefs. Where. Henry wonders, is the justification for such a selective appeal? Henry chides those theologians skeptical of biblical authority who attempt to give their prejudices an air of biblical legitimacy by citing only those passages that appear to support their views.

Readers familiar with Henry’s convictions will not be surprised to find him expounding and defending the inerrancy of the original manuscripts. Knowledgeable students of the inerrancy debate will probably not find much in his discussion that is new. The points he raises and the occasional qualification he introduces have always been part of the informed evangelical position. Unfortunately, many discussions of inerrancy by both friend and foe have been misinformed. Henry draws attention to several important qualifications that must be part of the inerrantist view. As one example, “Conformity to twentieth-century scientific measurement is not a criterion of accuracy to be projected back upon earlier generations.” Henry insists that inerrancy attaches to more than the Bible’s theological and moral teaching; it also extends to historical and scientific matters, at least as far as they are part of the Bible’s express message. Henry may surprise some readers with his identification of several problem passages for which he presently has no satisfactory answer. The inerrancy cause, Henry warns, is not strengthened by simply ignoring such problems. Henry believes that the history of the attack on inerrancy provides grounds for optimism that future discoveries will resolve the remaining difficulties. While the list of alleged errors in the Bible has grown shorter over the years, the list of the errors made by critics of Scripture grows longer.

Henry includes one entire chapter on biblical criticism, which he refuses to reject in principle. Christianity, he states, has nothing “to fear from truly scientific historical criticism. What accounts for the adolescent fantasies of biblical criticism are not its legitimate pursuits but its paramour relationships with questionable philosophic consorts.” Many evangelical scholars utilize the historical-critical method in ways compatible with biblical infallibility. “What is objectionable is not historical-critical method, but rather the alien presuppositions to which neo-Protestant scholars subject it.”

When Henry turns his attention to the person and work of the Holy Spirit, he notes that the same Spirit who inspired the Bible and illuminates the interpreter also serves as the instrument by which the truth of revelation is personally appropriated. The Holy Spirit is the agent of regeneration. The power of the Holy Spirit is present in the life of the twice born as their lives witness to the power of God’s revelation. Henry deplores several tendencies in the modern charismatic movement. The movement is weak at the critical point of its grounding in theology and in its acceptance of “psychic and mystical phenomena without adequately evaluating them.” Because it lacks an adequate systematic theology, the charismatic movement is “prone to a view of charismatic revelation and authority that competes at times with what the Bible teaches.” He cites, for example, the case of David Wilkerson of Melodyland School of Theology who has reportedly claimed normative authority for a private vision.

Henry proceeds to examine the power of the gospel on the individual and societal level. The Christian is to apply the gospel to social issues. Henry evaluates the Marxist alternative to Scripture as well as the efforts of liberal theologians to provide a Marxist interpretation of the Bible. Henry’s study concludes with a look at God’s future revelation of his glory in power and judgment when righteousness and justice will be vindicated and evil destroyed for all time.

Henry’s discussions are bound to become widely consulted treatments of the evangelical consensus. Critics of evangelicalism who have frequently found it convenient to challenge theological lightweights now have a heavyweight with which to contend. This is not to ignore problems in Henry’s work. One could hardly expect any theologian to pen the final word on issues so important and complex. The debates will continue, of course, but Henry’s work will have to be reckoned with. Dr. Henry has given the Christian church a remarkable new resource for its future reflection on God, revelation, and authority.

Briefly Noted

Church History: Reformation And After

Four Reformers: Luther, Melanchthon, Calvin, Zwingli (Augsburg), by Kurt Aland, is a handy introduction to these Reformers. God’s Man: A Novel on the Life of John Calvin (Baker), by D. Norton-Taylor, is a sympathetic treatment of an often misunderstood man. Baker has also reprinted R. C. Reed’s The Gospel As Taught by Calvin, a good introduction to Calvin’s thought.

The Banner of Truth Trust (Box 621, Carlisle. Pa.) makes the Parker Society set of The Writings of John Bradford (two volumes) available again. It is heavy but excellent reading. Thomas Boston’s classic The Crook in the Lot has been reprinted by Baker Book House. A short but effective study is Three Anglican Divines on Prayer: Jewel. Andrewes, and Hooker (Society of St. John the Evangelist. 980 Memorial Dr., Cambridge, Mass.) by John Booty.

The Huguenot Struggle for Recognition (Yale University Press), by N. M. Sutherland, is an excellent study of the French Reformation. Also from Yale University Press is the second printing of The Reformation in the Cities: The Appeal of Protestantism to Sixteenth-Century Germany and Switzerland by S. E. Ozment. This is a major, indispensable work.

Every student of church history will be glad to see that Daniel Neal’s standard. The History of the Puritans, or, Protestant Nonconformists. From the Reformation in 1517 to the Revolution in 1688 (three volumes), has been reprinted by Klock and Klock (2527 Girard Ave. N., Minneapolis. Minn.)

A challenging new study of the English revolution is Richard Baxter and the Millennium (Rowman and Littlefield. 81 Adams Dr., Totowa, N.J.) by N. M. Lamont. The English Civil War (Thames and Hudson), by Maurice Ashley, is a beautifully illustrated and well-written, concise history of that period. J. W. Williamson, in The Myth of the Conqueror: Prince Henry Stuart, a Study in the 17th Century Personation (AMS. 56 E. 13th St., N.Y.). writes the first modern biography of James I’s son, with significant new insights to offer. Two very different but nonetheless valuable biographies of royalty in this period are the generous treatment of Royal Charles: Charles II and the Restoration (Knopf) by Antonia Fraser and the more sharply put The Image of the King: Charles I and Charles 11 (Atheneum), by Richard Ollard.

The Days of the Fathers in Rosshire (Christian Focus Publications, Henderson Road, Inverness IV1 1SP, Scotland), by John Kennedy, is a reprint of a marvelous 1861 book recalling the godly days of old. The Happy Man: The Abiding Witness of Lachlan Mackenzie (Banner of Truth), is a collection of sermons, with a brief biographical sketch of this remarkable Scotsman. English Provincial Society from the Reformation to the Revolution: Religion. Politics, and Society in Kent 1500–1640 (Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, Cranbury, N.J.), by Peter Clark, is a massive and definitive study of great value. An abridged version of Lawrence Stone’s eminently readable and exhaustive The Family, Sex and Marriage in England 1500–1800 has been made available by Harper and Row, Colophon Books. An excellent study of “Christian Cabala” is Francis Yates’s The Occult Philosophy in the Elizabethan Age (Routledge and Kegan Paul). Faith, Reason, and the Plague: A Tuscan Story of the Seventeenth Century (available from Cornell University Press), by Carlo M. Cipolla, is the fascinating, moving story of a small village and its problems. Renaissance Drama and the English Church Year (University of Nebraska Press), by R. C. Hassel, is a major new study of value to students of theology and literature alike. R. G. Clouse has written an excellent survey in The Church in the Age of Orthodoxy and the Enlightenment: Consolidation and Challenge 1600–1700 (Concordia). Lost Country Life (Pantheon), by Dorothy Hartley, is an absolutely fascinating collection of just about anything anybody ever wanted to know about early English rural life.