How should i think of myself? What attitude should I adopt toward myself? These are contemporary questions of great importance, questions to which a satisfactory answer cannot be given without reference to the Cross.

A low self-image is common, since many modern influences dehumanize human beings and make them feel worthless. Wherever people are politically or economically oppressed, they feel demeaned. Racial and sexual prejudice have the same effect. As Arnold Toynbee put it, technology demotes persons into serial numbers, “punched on a card and designed to travel through the entrails of a computer.” Ethologists like Desmond Morris tell us that human beings are nothing but animals, and behaviorists like B. F. Skinner say that they are nothing but machines programmed to make automatic responses to external stimuli.

Further, the pressures of a competitive society make many feel like failures. And, of course, there is the personal tragedy of being unloved and unwanted. All these are causes of a low self-image.

In overreaction to this set of influences is the popular movement in the opposite direction. With the laudable desire to build self-respect, it speaks of human potential as virtually limitless. Others emphasize the need to love ourselves. In his perceptive book Psychology As Religion: The Cult of Self-Worship (1977), Paul Vitz cites the following as an illustration of “selfist jargon”:

“I love me. I am not conceited. I’m just a good friend to myself. And I like to do whatever makes me feel good.…”

Another example is this limerick:

There once was a nymph named Narcissus,

Who thought himself very delicious;

So he stared like a fool

At his face in a pool,

And his folly today is still with us.

A Common Error

In spite of widespread teaching to the contrary, the Mosaic injunction, endorsed by Jesus, “You shall love your neighbor as yourself,” is not a command to love ourselves. Three arguments may be adduced.

Grammatically, Jesus did not say that the second and third commandments are to love our neighbor and ourselves, but that the second commandment is to love our neighbor as we love ourselves. Self-love here is a fact we should recognize (and use to guide our conduct, as with the Golden Rule), but it is not a virtue to be commended.

Linguistically, agape love means self-sacrifice in the service of others. It cannot therefore be self-directed. The concept of sacrificing ourselves to save ourselves is nonsense.

Theologically, self-love is the biblical notion of sin. One of the marks of the last days in which we live, Paul writes, is that people will be “lovers of self” instead of “lovers of God” (2 Tim. 3:1–4).

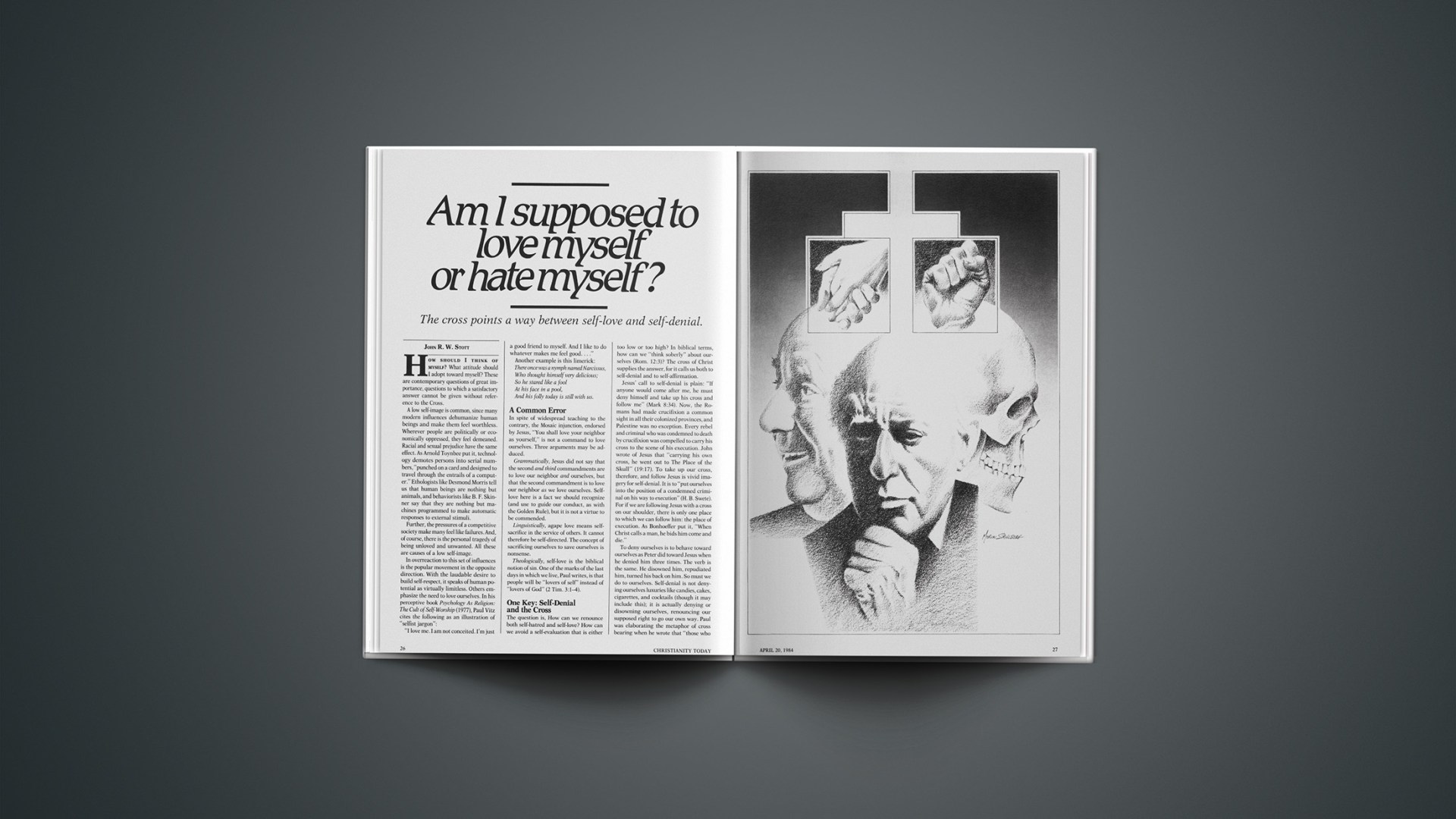

One Key: Self-Denial And The Cross

The question is, How can we renounce both self-hatred and self-love? How can we avoid a self-evaluation that is either too low or too high? In biblical terms, how can we “think soberly” about ourselves (Rom. 12:3)? The cross of Christ supplies the answer, for it calls us both to self-denial and to self-affirmation.

Jesus’ call to self-denial is plain: “If anyone would come after me, he must deny himself and take up his cross and follow me” (Mark 8:34). Now, the Romans had made crucifixion a common sight in all their colonized provinces, and Palestine was no exception. Every rebel and criminal who was condemned to death by crucifixion was compelled to carry his cross to the scene of his execution. John wrote of Jesus that “carrying his own cross, he went out to The Place of the Skull” (19:17). To take up our cross, therefore, and follow Jesus is vivid imagery for self-denial. It is to “put ourselves into the position of a condemned criminal on his way to execution” (H. B. Swete). For if we are following Jesus with a cross on our shoulder, there is only one place to which we can follow him: the place of execution. As Bonhoeffer put it, “When Christ calls a man, he bids him come and die.”

To deny ourselves is to behave toward ourselves as Peter did toward Jesus when he denied him three times. The verb is the same. He disowned him, repudiated him, turned his back on him. So must we do to ourselves. Self-denial is not denying ourselves luxuries like candies, cakes, cigarettes, and cocktails (though it may include this); it is actually denying or disowning ourselves, renouncing our supposed right to go our own way. Paul was elaborating the metaphor of cross bearing when he wrote that “those who belong to Christ Jesus have crucified the sinful nature with its passions and desires” (Gal. 5:24). We have taken our slippery self and nailed it to Christ’s cross.

Another Key: Self-Affirmation And The Cross

I wonder how you have reacted to the last couple of paragraphs? I hope you have felt uneasy about them. For they have expressed such a negative attitude to self that they appear to align Christians with the bureaucrats and technocrats, the ethologists and behaviorists, in demeaning human beings. It is not that what I have written is untrue (for Jesus said it), but that it is only one side of the truth. It implies that our “self” is wholly bad and must therefore be totally rejected, indeed “crucified”!

But we must not overlook another strand in Scripture. Alongside Jesus’ explicit call to self-denial is his implicit call to self-affirmation (which is not the same as self-love). Nobody who reads the Gospels as a whole could possibly gain the impression that Jesus had a negative attitude to human beings himself, or encouraged one in others. The opposite is the case.

Consider, first, his teaching about people. He spoke of their “value” in God’s sight. They are “much more valuable” than birds or beasts, he said (Matt. 6:26; 12:12). What was the ground of this value judgment? It must have been the doctrine of Creation, which Jesus took over from the Old Testament. It is the divine image in us that gives us our distinctive value. In his excellent little book The Christian Looks at Himself (1975), Prof. Anthony Hoekema quotes a young black who, rebelling against the inferiority feelings inculcated in him by whites, put up this banner in his room: “I’m me and I’m good, ’cos God don’t make junk.”

Then, second, there was Jesus’ attitude toward people. He despised nobody. On the contrary, he went out of his way to honor those the world dishonored, and to accept those the world rejected. He spoke courteously to women in public. He invited children to come to him. He spoke words of hope to Samaritans and Gentiles. He allowed leprosy sufferers to approach him and a prostitute to anoint and kiss his feet. He ministered to the poor and hungry and made friends with the outcasts of society. In all this, his love for human beings shone out. He acknowledged their value and loved them, and by loving them he increased their value.

Third, and in particular, we must remember Jesus’ mission and death for people. He had come to serve, not to be served, and to give his life as a ransom for many (Mark 10:45). Nothing indicates more clearly the value Jesus placed on people than his determination to suffer and die for them. He was the Good Shepherd who came into the desert to seek and save only one lost sheep, and who laid down his life for his sheep. It is only when we look at the cross that we see the true worth of human beings. As William Temple expressed it, “My worth is what I am worth to God, and that is a marvelous great deal because Christ died for me.”

Resolving The Paradox

We have seen so far that the cross of Christ is both a proof of the value of the human self and a picture of how to deny and crucify it. How can this biblical paradox be resolved? How is it possible to value ourselves and to deny ourselves simultaneously?

The problem arises because we discuss and develop alternative attitudes to ourselves before we have defined this “self” we are talking about. Our “self” is not a simple entity that is either wholly good or wholly evil, one that should therefore be either totally valued or totally denied. Our “self” is a complex entity of good and evil, glory and shame, which therefore requires that we develop more subtle attitudes.

What we are (our self or personal identity) is partly the result of the Creation (the image of God), and partly the result of the Fall (the image defaced). The self we are to deny, disown, and crucify is our fallen self, everything within us that is incompatible with Jesus Christ (hence Christ’s command, “let him deny himself and follow me”). The self we are to affirm and value is our created self, everything within us that is compatible with Jesus Christ (hence his statement that if we lose ourselves by self-denial we shall find ourselves). True self-denial (the denial of our false, fallen self) is not the road to self-destruction, but the road to self-discovery.

So, then, whatever we are by creation, we must affirm: our rationality, our sense of moral obligation, our masculinity and feminity, our aesthetic appreciation and artistic creativity, our stewardship of the fruitful earth, our hunger for love and community, our sense of the transcendent mystery of God, and our inbuilt urge to fall down and worship him. All this is part of our created humanness. True, it has all been tainted and twisted by sin. Yet Christ came to redeem and not destroy it. So we must affirm it.

But whatever we are by the Fall, we must deny or repudiate: our irrationality; our moral perversity; our loss of sexual distinctives; our fascination with the ugly; our lazy refusal to develop God’s gifts; our pollution and spoliation of the environment; our selfishness, malice, individualism, and revenge, which are destructive of human community; our proud autonomy; and our idolatrous refusal to worship God. All this is part of our fallen humanness. Christ came not to redeem this but to destroy it. So we must deny it.

Dignity And Depravity

There is, therefore, a great need for discernment in our self-understanding. Who am I? What is my “self”? Answer: I’m a Jekyll and Hyde, a mixed-up kid, having both dignity, because I was created in God’s image, and depravity, because I am fallen and rebellious. I am both noble and ignoble, beautiful and ugly, good and bad, upright and twisted, image of God and slave of the Devil. My true self is what I am by creation, which Christ came to redeem. My fallen self is what I am by the Fall, which Christ came to destroy.

Only when we have discerned which is which within us shall we know what attitude to adopt toward evil. We must be true to our true self and false to our false self. We must be fearless in affirming all that we are by creation, and ruthless in disowning all that we are by the Fall.

Moreover, Christ’s cross teaches us both attitudes. On one hand, it is the measure of the value of our true self, since Christ died for us. On the other hand, it is the model for the denial of our false self, since we are to nail it to the cross and so put it to death.

Tim Stafford is a free-lance writer living in Santa Rosa, California. He is a distinguished contributor to several magazines. His latest book is Do You Sometimes Feel Like a Nobody? (Zondervan, 1980).