Benjamin Weir returned to the United States in September after being held hostage in Lebanon for more than 16 months. A missionary in Lebanon for 30 years, the Presbyterian minister was snatched off a West Beirut sidewalk in May 1984. His abductors, members of a group called Islamic Jihad (Islamic Holy War), have claimed responsibility for the kidnapings of seven other U.S. citizens.

One of those Americans, Jeremy Levin, came home in February. Still imprisoned are Lawrence Martin Jenco, an official with Catholic Relief Services; David Jacobsen, director of the American University Hospital; Thomas Sutherland, dean of agriculture at the American University of Beirut (AUB); Terry Anderson, an Associated Press correspondent; and Peter Kilburn, an AUB librarian. Another of those taken hostage, U.S. embassy official William Buckley, is believed to have been killed.

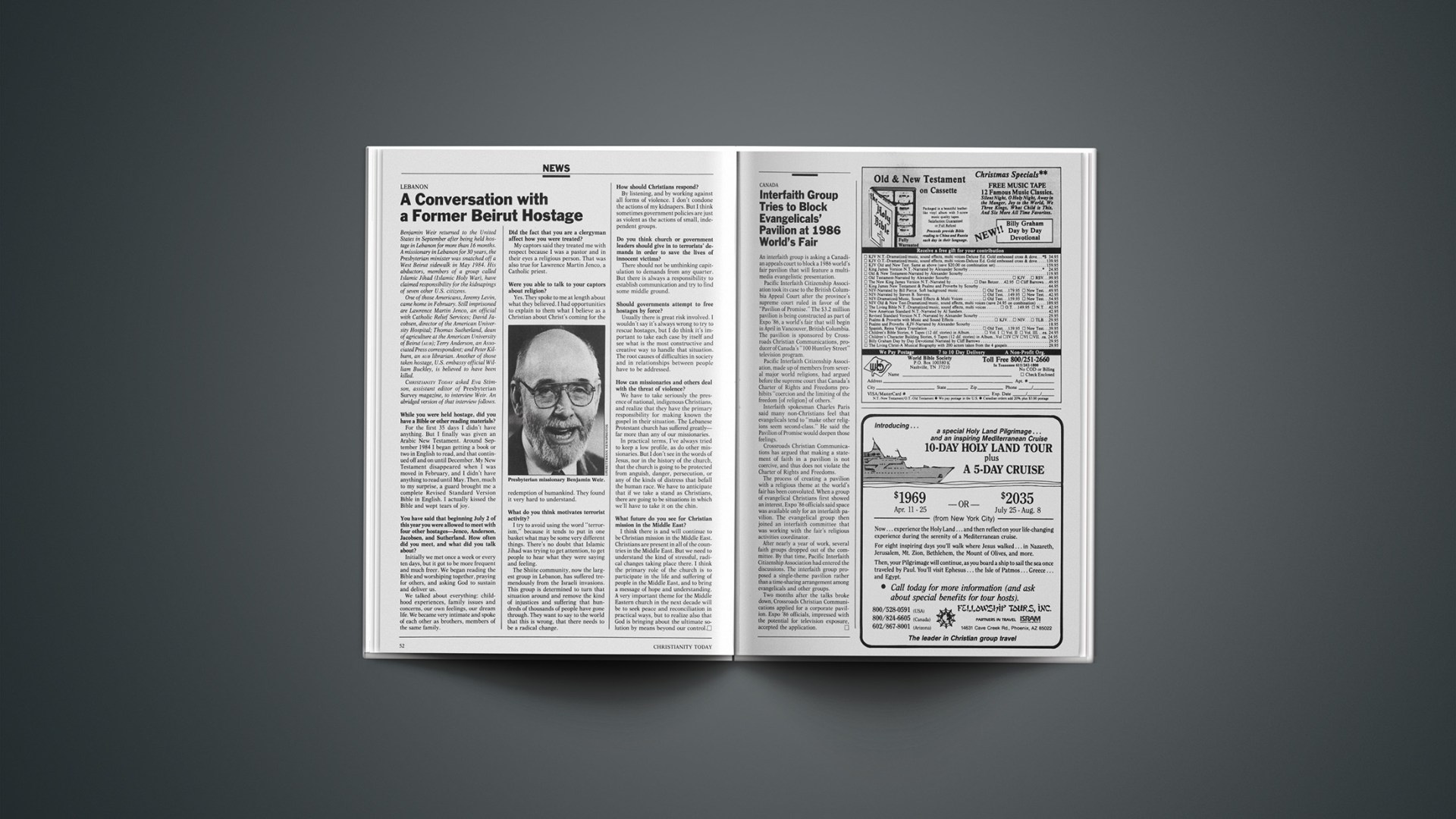

CHRISTIANITY TODAY asked Eva Stimson, assistant editor of Presbyterian Survey magazine, to interview Weir. An abridged version of that interview follows.

While you were held hostage, did you have a Bible or other reading materials?

For the first 35 days I didn’t have anything. But I finally was given an Arabic New Testament. Around September 1984 I began getting a book or two in English to read, and that continued off and on until December. My New Testament disappeared when I was moved in February, and I didn’t have anything to read until May. Then, much to my surprise, a guard brought me a complete Revised Standard Version Bible in English. I actually kissed the Bible and wept tears of joy.

You have said that beginning July 2 of this year you were allowed to meet with four other hostages—Jenco, Anderson, Jacobsen, and Sutherland. How often did you meet, and what did you talk about?

Initially we met once a week or every ten days, but it got to be more frequent and much freer. We began reading the Bible and worshiping together, praying for others, and asking God to sustain and deliver us.

We talked about everything: childhood experiences, family issues and concerns, our own feelings, our dream life. We became very intimate and spoke of each other as brothers, members of the same family.

Did the fact that you are a clergyman affect how you were treated?

My captors said they treated me with respect because I was a pastor and in their eyes a religious person. That was also true for Lawrence Martin Jenco, a Catholic priest.

Were you able to talk to your captors about religion?

Yes. They spoke to me at length about what they believed. I had opportunities to explain to them what I believe as a Christian about Christ’s coming for the redemption of humankind. They found it very hard to understand.

What do you think motivates terrorist activity?

I try to avoid using the word “terrorism,” because it tends to put in one basket what may be some very different things. There’s no doubt that Islamic Jihad was trying to get attention, to get people to hear what they were saying and feeling.

The Shiite community, now the largest group in Lebanon, has suffered tremendously from the Israeli invasions. This group is determined to turn that situation around and remove the kind of injustices and suffering that hundreds of thousands of people have gone through. They want to say to the world that this is wrong, that there needs to be a radical change.

How should Christians respond?

By listening, and by working against all forms of violence. I don’t condone the actions of my kidnapers. But I think sometimes government policies are just as violent as the actions of small, independent groups.

Do you think church or government leaders should give in to terrorists’ demands in order to save the lives of innocent victims?

There should not be unthinking capitulation to demands from any quarter. But there is always a responsibility to establish communication and try to find some middle ground.

Should governments attempt to free hostages by force?

Usually there is great risk involved. I wouldn’t say it’s always wrong to try to rescue hostages, but I do think it’s important to take each case by itself and see what is the most constructive and creative way to handle that situation. The root causes of difficulties in society and in relationships between people have to be addressed.

How can missionaries and others deal with the threat of violence?

We have to take seriously the presence of national, indigenous Christians, and realize that they have the primary responsibility for making known the gospel in their situation. The Lebanese Protestant church has suffered greatly—far more than any of our missionaries.

In practical terms, I’ve always tried to keep a low profile, as do other missionaries. But I don’t see in the words of Jesus, nor in the history of the church, that the church is going to be protected from anguish, danger, persecution, or any of the kinds of distress that befall the human race. We have to anticipate that if we take a stand as Christians, there are going to be situations in which we’ll have to take it on the chin.

What future do you see for Christian mission in the Middle East?

I think there is and will continue to be Christian mission in the Middle East. Christians are present in all of the countries in the Middle East. But we need to understand the kind of stressful, radical changes taking place there. I think the primary role of the church is to participate in the life and suffering of people in the Middle East, and to bring a message of hope and understanding. A very important theme for the Middle Eastern church in the next decade will be to seek peace and reconciliation in practical ways, but to realize also that God is bringing about the ultimate solution by means beyond our control.