Religious and political leaders disagree over how to pressure the white minority government.

Stiffer U.S. sanctions against the government of South Africa appeared inevitable as Congress returned this month from its Labor Day recess. Still in question, however, is the effect sanctions will have on South Africa’s entrenched minority government, as well as on the United States’ ability to encourage change there. South Africa’s system of apartheid denies voting rights and other basic rights of citizenship to the country’s black majority.

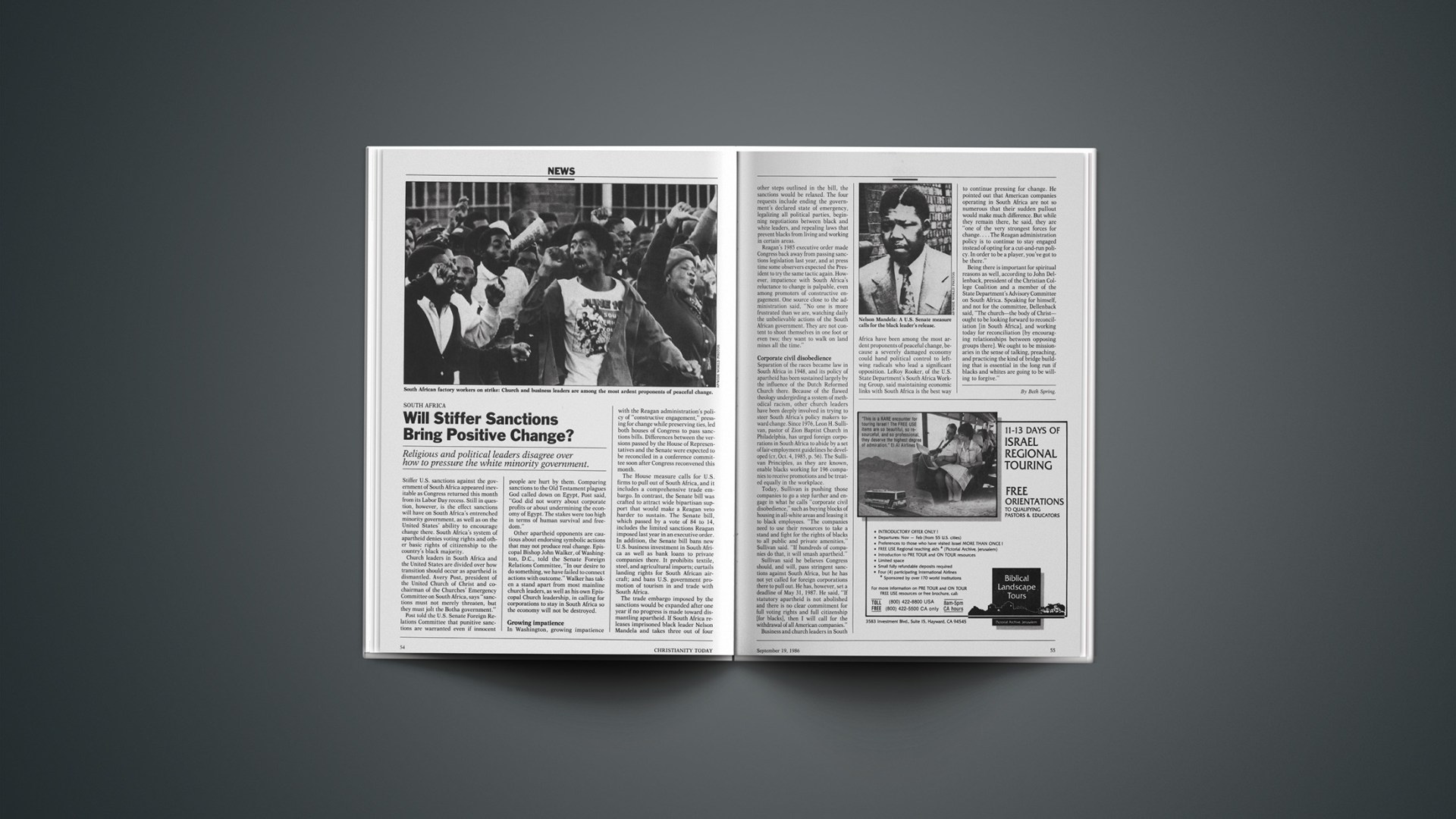

Church leaders in South Africa and the United States are divided over how transition should occur as apartheid is dismantled. Avery Post, president of the United Church of Christ and co-chairman of the Churches’ Emergency Committee on South Africa, says “sanctions must not merely threaten, but they must jolt the Botha government.”

Post told the U.S. Senate Foreign Relations Committee that punitive sanctions are warranted even if innocent people are hurt by them. Comparing sanctions to the Old Testament plagues God called down on Egypt, Post said, “God did not worry about corporate profits or about undermining the economy of Egypt. The stakes were too high in terms of human survival and freedom.”

Other apartheid opponents are cautious about endorsing symbolic actions that may not produce real change. Episcopal Bishop John Walker, of Washington, D.C., told the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, “In our desire to do something, we have failed to connect actions with outcome.” Walker has taken a stand apart from most mainline church leaders, as well as his own Episcopal Church leadership, in calling for corporations to stay in South Africa so the economy will not be destroyed.

Growing Impatience

In Washington, growing impatience with the Reagan administration’s policy of “constructive engagement,” pressing for change while preserving ties, led both houses of Congress to pass sanctions bills. Differences between the versions passed by the House of Representatives and the Senate were expected to be reconciled in a conference committee soon after Congress reconvened this month.

The House measure calls for U.S. firms to pull out of South Africa, and it includes a comprehensive trade embargo. In contrast, the Senate bill was crafted to attract wide bipartisan support that would make a Reagan veto harder to sustain. The Senate bill, which passed by a vote of 84 to 14, includes the limited sanctions Reagan imposed last year in an executive order. In addition, the Senate bill bans new U.S. business investment in South Africa as well as bank loans to private companies there. It prohibits textile, steel, and agricultural imports; curtails landing rights for South African aircraft; and bans U.S. government promotion of tourism in and trade with South Africa.

The trade embargo imposed by the sanctions would be expanded after one year if no progress is made toward dismantling apartheid. If South Africa releases imprisoned black leader Nelson Mandela and takes three out of four other steps outlined in the bill, the sanctions would be relaxed. The four requests include ending the government’s declared state of emergency, legalizing all political parties, beginning negotiations between black and white leaders, and repealing laws that prevent blacks from living and working in certain areas.

Reagan’s 1985 executive order made Congress back away from passing sanctions legislation last year, and at press time some observers expected the President to try the same tactic again. However, impatience with South Africa’s reluctance to change is palpable, even among promoters of constructive engagement. One source close to the administration said, “No one is more frustrated than we are, watching daily the unbelievable actions of the South African government. They are not content to shoot themselves in one foot or even two; they want to walk on land mines all the time.”

Corporate Civil Disobedience

Separation of the races became law in South Africa in 1948, and its policy of apartheid has been sustained largely by the influence of the Dutch Reformed Church there. Because of the flawed theology undergirding a system of methodical racism, other church leaders have been deeply involved in trying to steer South Africa’s policy makers toward change. Since 1976, Leon H. Sullivan, pastor of Zion Baptist Church in Philadelphia, has urged foreign corporations in South Africa to abide by a set of fair-employment guidelines he developed (CT, Oct. 4, 1985, p. 56). The Sullivan Principles, as they are known, enable blacks working for 196 companies to receive promotions and be treated equally in the workplace.

Today, Sullivan is pushing those companies to go a step further and engage in what he calls “corporate civil disobedience,” such as buying blocks of housing in all-white areas and leasing it to black employees. “The companies need to use their resources to take a stand and fight for the rights of blacks to all public and private amenities,” Sullivan said. “If hundreds of companies do that, it will smash apartheid.”

Sullivan said he believes Congress should, and will, pass stringent sanctions against South Africa, but he has not yet called for foreign corporations there to pull out. He has, however, set a deadline of May 31, 1987. He said, “If statutory apartheid is not abolished and there is no clear commitment for full voting rights and full citizenship [for blacks], then I will call for the withdrawal of all American companies.”

Business and church leaders in South Africa have been among the most ardent proponents of peaceful change, because a severely damaged economy could hand political control to left-wing radicals who lead a significant opposition. LeRoy Rooker, of the U.S. State Department’s South Africa Working Group, said maintaining economic links with South Africa is the best way to continue pressing for change. He pointed out that American companies operating in South Africa are not so numerous that their sudden pullout would make much difference. But while they remain there, he said, they are “one of the very strongest forces for change.… The Reagan administration policy is to continue to stay engaged instead of opting for a cut-and-run policy. In order to be a player, you’ve got to be there.”

Being there is important for spiritual reasons as well, according to John Dellenback, president of the Christian College Coalition and a member of the State Department’s Advisory Committee on South Africa. Speaking for himself, and not for the committee, Dellenback said, “The church—the body of Christ—ought to be looking forward to reconciliation [in South Africa], and working today for reconciliation [by encouraging relationships between opposing groups there]. We ought to be missionaries in the sense of talking, preaching, and practicing the kind of bridge building that is essential in the long run if blacks and whites are going to be willing to forgive.”

By Beth Spring.