Where Did The Power Go?

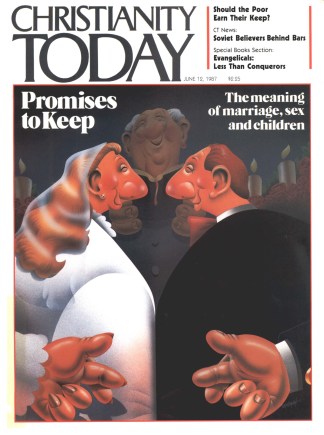

Less Than Conquerors: How Evangelicals Entered the Twentieth Century, by Douglas Frank (Eerdmans, x + 310 pp.; $14.95, paper). Reviewed by Tim Stafford.

Douglas Frank says that from 1850 to 1920 evangelicals lost control of America. At mid-century they stood at the head of an optimistic, self-confident nation. By 1920 they had become a somewhat baffled minority within a pluralist, secularist nation.

Industrial capitalism broke up the world of independent towns and brought purposeless upheaval. Evangelical pieties, honed on farms and villages, seemed increasingly irrelevant to a world in which distant, impersonal forces ruled. Additional pressures came from the acceptance of evolution, and the introduction of radical critiques of Scripture. Evangelicals felt, subliminally at least, that they were becoming insignificant figures in a landscape that had once belonged to them.

Frank’s fundamental assumption is that this loss of power was God-given. Our heroic forefathers, he says, by well-meaning industry, led us astray.

Frank has, it appears, accepted Barth’s assessment of religion as humanity’s greatest defense against God. Evangelicals have a considerable tradition of scoffing at religiosity, but seldom have we taken seriously the fact that we too are in the religion business. That is, in a way, Frank’s point: evangelicals have thought of themselves as purer than others, when under God’s judgment they are equally in need. In losing their power, evangelicals had a great opportunity to experience God’s grace as that which helps the helpless and blesses the poor in spirit. Instead, they managed to shore up and reassert their self-confidence. Frank analyzes three popular currents that boosted the evangelical self-image.

Back In Control, Someday

The first current was dispensationalism. As the times became threatening, and Christian influences less significant, postmillennial optimism about America became harder to preserve. Evangelicals, Frank suggests, managed to reassert their control of history through a wholesale shift to a variety of dispensationalism that assured them that they alone had the key to understand the world’s threatening state of affairs and would someday once again be the people in charge. They substituted symbolic or eschatological control for their lost societal influence.

The Victorious Christian Life (closely linked to the British Keswick movement, and known by the slogan “let go, let God”) solved another problem. Before the Civil War, evangelicals had put tremendous emphasis on manly character—an appropriate emphasis for people who expected to lead America into the millennium. Manly character was about the mastery of life. But in an increasingly complex and impersonal society, mastery became far more difficult. Getting the victory, as it was called, shifted mastery from external events to an internal realm. There, at least, one could exercise complete control.

The third current was embodied in a man, Billy Sunday, who was the greatest revivalist in history until the advent of Billy Graham. Frank shows that Sunday’s crusades were more passionate about reforming lives (from alcohol, preeminently, but from other passions as well) and making them “manly” than about salvation by grace. His invitation was, frequently, “How many of you men will say, ‘Bill, I believe the Christian life is the right and manly life, and by the grace of God, from now on I’ll do my best for the Lord and for his truth’?”

Why, then, was Sunday so acclaimed by evangelicals? Frank concludes that the colorful evangelist became a kind of hero to evangelicals—hero in the ancient sense, a warrior who goes out to fight our battles for us. When Sunday railed pitilessly against the evils of booze, Frank suggests, evangelicals found a kind of vicarious triumph in watching him devastate the forces of evil.

God’s Magnificence, Not Ours

Through reshaping their theology, and living vicariously through public heroes, Frank says, evangelicals avoided facing their own inability to cope, their lack of applicable answers, their helplessness before overpowering forces. In short, they used their religion as a way to gain some sort of control over a difficult life.

But the grace of Jesus Christ, says Frank, is not meant to help us back into a position of power. It is all about God’s magnificence, and not about our magnificence at all. It requires a spirit of constant repentance, of weeping, of waiting for God’s salvation. Frank sees little of that in our heritage from this period.

Frank’s critique is not what one would call balanced. (He would say, I am sure, that God’s critique is not what one would call balanced, either.) Yet his prose never, to my ear, reveals a mean spirit. Clearly what he criticizes, he sees in himself.

Nor does he denigrate the past merely to substitute his own program. He offers no hope except repentance. My question would be whether repentance (poverty of spirit, humility) is easily detected in historical documents. Is repentance usually a public phenomenon? It may be that the figures he considers knew plenty of repentance, but felt compelled to rise from their knees and lead a movement as best they knew how. I consider evangelical traditions to be larded with concern for prayerful repentance, as well as the busy religion that Frank critiques. I suspect that it was from these traditions, as well as from the Bible, that Frank got his concerns.

Regardless, Douglas Frank’s book is the most spiritually provocative reading I have done in some time, worth buying for the historical analysis alone, but unique in its deeply personal probing of history and Scripture. In this optimistic, activistic time for evangelicals, it is unusual to encounter someone swimming against the stream with such rigor.

Christianity Today Visits Douglas Frank

As befits our image of one who speaks a prophetic word, the fortyish Douglas Frank lives 21 miles up a winding mountain road from the small town of Ashland, Oregon. Son of Walter Frank, head of Greater Europe Mission for 20 years, his childhood memories-include six weeks every summer at camp meetings, where dispensationalism and the Victorious Christian Life were taught, and where the open-air tabernacle had sawdust on the floor for kneeling sinners.

As a professor of history at Trinity College, Frank and several colleagues launched an interdisciplinary study program at an abandoned lumber camp in southern Oregon. By 1982 he and his family had moved to the site, where seven families live year-round, conducting a special fall semester under the auspices of Houghton College.

Asked whether he needed courage to publish Less Than Conquerors, Frank answered, “That’s hard to say. Since I’m an evangelical I’m not really in touch with my feelings.”

He continued in a more serious vein: “I’ve told my parents that I am anxious about their reaction. But as for everyone else, I never really thought much about it. I lived these questions so intensely during the six years I was writing that it became my own private world.”

by Tim Stafford.

Giving Up On The Powers

Christian Anarchy: Jesus’ Primacy Over the Powers, by Vernard Eller (Eerdmans, xiv + 267 pp.; $13.95, paper). Reviewed by Rodney Clapp.

In a time of their pronounced political and social reinvolvement, conservative Christians may be open to considering a variety of political options. Even in an atmosphere of openness, however, the recommendation of Church of the Brethren theologian Vernard Eller is startling. In his latest book, Eller suggests that churchgoers take up the cross—and become Christian anarchists.

Eller carefully qualifies this explosive word. The root archy (or “arky,” as Eller anglicizes it) comes from the Greek meaning “principle,” “prince,” and the like. The prefix an simply means “without” or “un.” In Christ’s resurrection, God has shown himself to be victorious over all earthly powers and principalities. For Eller, this means the Christian should be an “anarchist,” allowing real allegiance to no human prince or principle, but to Jesus alone.

Thus he is unhappy with his fellow pacifists, who too often “use a person’s stand on nuclear arms as a truer test of a person’s Christianity than his stand on the biblical proclamation as to who Christ is. This is zealotism, the prioritizing of a human arky above the true God.” If you are cheering because you think Eller has denounced a folly crying for denunciation, substitute the words “abortion” or “Republican party” for “nuclear arms” and realize Eller would consider the resulting sentences no less true.

Eller is not saying there are not choices that are relatively better, only that there is a single choice that is absolute: the choice for or against Jesus Christ. In our human fallibility, we may arrive at positions and principles derived from our faith, but we should never equate them with the faith.

Balancing Act

Politically speaking, Eller calls Christians to a difficult dialectical balancing act, between the two poles of the establishment and revolution. We are not to choose for or against one or the other. Since the establishment and revolution are both human arkys, Christians must judge establishment or revolutionary proposals on a case-by-case basis, pragmatically supporting the proposals that appear to be most consonant with the justice and love of God.

But the establishment, revolution, and all other human arkys are pretentious: they always promise more than they can deliver. Compared to other citizens, Eller suggests, Christians should be less ideological and more realistic, never supposing any arky will usher in the kingdom on earth. On a scale of 1 to 100, with 100 representing God’s righteousness, Eller guesses the best ever humanly achieved is a 3.

One of the most refreshing aspects of the book is Eller’s method for demonstrating the dialectic of Christian anarchy. He is not preoccupied with making his case at the expense of the opponents of his position. Rather, he is hardest on the positions nearest to his own, ferreting out in relentless, Kierkegaardian fashion the inconsistencies of the peace movement, feminism, and radical discipleship groups such as the Sojourners Community. Chapter 4, “On Selective Sin and Righteousness,” is the best of the book.

Defective Dialectic

But Eller’s dialectic falls short on at least one count. He argues so vigorously for the supremacy of the individual over the institutional that the social aspects of the faith may be given short shrift. Though he makes perfunctory remarks about the church as a social entity, Eller seems to gravitate toward the individual heroically separate from the church, answering independently and directly to the gospel.

Thus his examples of anarchic Christianity have to do with individuals and not with Christian communities—Jacques Ellul’s various political adventures, Karl Barth’s and Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s famous German stands, the celebrated refusal of Vernard’s son Enten to register for the draft, and Vernard’s own “anarchic” relation to his chosen profession of education.

Yet if arkys are social forces, they will overwhelm unconnected individuals. Eller recognizes as much in the case of Barth and Bonhoeffer with the Third Reich. In that instance, both eased the dialectical tension of establishment versus revolution and ended up supporting Christian revolution against Hitler.

Eller excuses Barth’s and Bonhoeffer’s fall from Christian anarchy by saying, “I see them … as two human beings who—under terrible pressure—simply found themselves unable to live up to their own ideals.” One wonders if Eller’s abiding suspicion about institutions prevents him from going ahead to write that Barth and Bonhoeffer needed Christian communities—churches—that would stand with them against the demands of the reprehensible Third Reich and revolution. To put it more generally: If institutions (particularly the church) cannot to some extent be redeemed, there is little hope for individuals.

Whatever the debatable points of Christian Anarchy, it unwaveringly presses home the utter centrality of the gospel. Throughout we find extended biblical exegesis, clear argument, and wit uncommon for a theologian. Christian Anarchy is a lucid synthesis of some 30 years of thinking and writing on the Christian’s relation to the world, a fresh and readable compendium of the Anabaptist witness that—more and more Christians outside that tradition are believing—is needed now as much as ever.

Explosive Issues

Nuclear Arms: Two Views on World Peace, by Myron S. Augsburger and Dean C. Curry (Word, viii + 186 pp.; $14.95, hardcover). Reviewed by Barbara Connell-Bishop, a Washington, D.C. based writer and founder of Greenhome, a women’s retreat and spiritual enrichment home.

“What divides us is not what the Bible says, but what we bring to the Bible.”

Never has this saying been more true than in the recently published Nuclear Arms: Two Views on World Peace. Contributors Myron S. Augsburger and Dean C. Curry square off in true debate style, complete with rebuttals. Thus Word Books begins its series “The Issues of Christian Conscience” with the hot topic of nuclear armament, and promises to continue to “make available discussions by top-flight experts on some of the most important problems which we confront.…”

In his introduction to the discussion, Vernon Grounds makes clear that the series is “designed to be informative, not propagandists,” that because the Bible does not provide specific guidelines regarding (in this case) thermonuclear war, there will undoubtedly be a “clash of radically opposing viewpoints among equally sincere, rational, and well-informed Christians.” It is the purpose of this series to provide a forum for the discussion; and it is for the readers to determine which rational, sincere, and well-informed side they will take.

In And Out Of Focus

Both Augsburger and Curry do a convincing job of arguing their respective sides. And both get equally fuzzy—about such things as our responsibility to be “in the world and not of the world”; or what “loving my neighbor as myself” really means when my neighbor is pointing a gun at a small, defenseless child.

Perhaps the greatest difference between the two authors is the orientation of their respective academic disciplines. Curry, who is chairman of the history and political science department at Messiah College, rests his presentation squarely upon his background as a political scientist. On the other hand, Augsburger, who is pastor of Washington Community Fellowship, comes to the discussion from his training as a theologian. And while both have done their homework admirably, the radical difference in their points of origin is obvious throughout the dialogue.

For Christians trying to weigh divergent “ultimate truths,” the decision must always come down to individual choice. Information is always welcome, coercion—whether from activist bishops or radical communitarians—is not.

Word Books should be commended for jumping into the fray, but perhaps the editors should review their strategy for future volumes in the series. In the case of Nuclear Arms: Two Views on World Peace, the initial sections by Curry and Augsburger are good representations of the Just War and the Pacifist/Biblical Realist positions respectively. However, the “Arguments” section, in which the authors critique each other, adds little to the discussion. It merely heightens the tension one already feels when approaching a book like this, and it leaves the reader wondering who won.

Perhaps the editors should have asked an additional scholar to dig beneath Curry’s and Augsburger’s arguments to see what they hold in common. Or perhaps they could have pushed Curry and Augsburger to note their commonalities and to be clear about the difference each has in emphasis, explicitly noting at what points they diverge (e.g., is effectiveness or witness more important?). Such effort might give readers the feeling that the book is trying to help them arrive at a decision, rather than simply contributing to the polarization.

If it is true that “what divides us is not what the Bible says, but what we bring to the Bible,” we have a long way to go before we resolve many an issue. But, if the better part of grace is in seeing the commonalities and not the differences, perhaps it is not too far.

Larry Sibley, who teaches practical theology at Westminster Theological Seminary in Philadelphia, examines four recent books for pastors and others who help people in trouble.

Despised and Rejected of Men

AIDS: Personal Stories in Pastoral Perspective, by Earl E. Shelp, Ronald H. Sunderland, and Peter W. A. Mansell, M.D. (Pilgrim, 205 pp.; $7.95, paper).

Aids presents the church with a challenge and an opportunity. The public is afraid—of infection, of uncertainty, of death, and of sexuality. If the church will embody the good news of God’s loving reign, it can replace fear with information and with models of care for the ill and ostracized. This book is one attempt to aid. Does it fill the bill?

The authors provide information: the medical facts, the people who have AIDS, the effects on their families and lovers and on those who care for them. This personal profile of pain was assembled through 27 in-depth interviews and does its job. No attempt is made to evaluate, only to describe.

The response of the church has been “at best, hesitant and ambivalent and, at worst, negligent.” It ought to be “positive, compassionate” to groups who are “despised and rejected” (mainly gays and drug users). The authors propose that we understand the at-risk population as “the alien in the midst.” Christians “are commanded to show, not merely to one another but to the neighbor and stranger, that perfect love casts out fear.” Just as Christ touched the leper, no matter what the moral stigma, so we must be ready to serve in his name.

A final chapter comments from a pastoral perspective.

There is much to commend here: a clear understanding of the needs of suffering people, and an emphasis on a ministry that sets right, comforts, and reconciles.

Whether AIDS is retribution from God is seen as “complex and beyond the scope of this discussion.” But whatever the authors answer to that question, it would not affect their thesis: “The means by which a person contracted the AIDS virus or his or her life-style does not lessen the obligation of the church to care for him or her.”

Healing the Horror of Sexual Abuse

Child Sexual Abuse, by Maxine Hancock and Karen Burton Mains (Harold Shaw, 197 pp.; $7.95, paper).

This book exposes a long-hidden agony. The research and charts (which demonstrate how child sexual abuse has entered even evangelical homes) and the “voices” (quoted from interviews) are a tapestry of searing pain.

But this book is also help. After four chapters that give content and shape to child sexual abuse (usually girls, but sometimes boys, with 77.4% of the abusers being a parent), its aftermath and the problems it creates, the authors move on to steps of healing. The next five chapters are realistic: “Healing can be instantaneous for some.… But most of the time, healing is deliberate and orderly.” The processes of forgiveness (of self and others) and opening to God are outlined well.

As the authors expose the problem, they occasionally include a very helpful feature. “Something You Can Do Right Now” capsulizes specific steps to be taken: Bible study; what to do and say, to whom, when. The typical abuser is profiled in a way that helps us understand, but not excuse. Mothers of the abused are also addressed and given specific help so that they can be helpers.

Throughout the book, which is primarily for those who have been abused as children, there are comments directed to those who would like to be enablers of healing. Although their facts are grim, Hancock and Mains also persuade that there is hope for those who will grasp this nettle firmly. God heals even this horror.

Fear of Dying

A Theology for Aging, by William L. Hendricks (Broadman, 300 pp.; $10.95, cloth).

We recoil so much from the threat of old age that we pay millions to remove its wrinkles, colors, and shapes. At the core of this fear is a theology of despair. William Hendricks, on the other hand, has a theology of hope contextualized for the aging.

Beginning at the end (“last things”), he proceeds to the beginning (the Bible). In between he discusses conversion, the church, humanness, creation and providence, the Holy Spirit, Christ, and the attributes of God—all the standard theological topics in the light of growing older. The content is evangelical, creatively presented in metaphors, in phrases from hymns, and in common experiences of the aging. Appendixes on suicide and biblical authority, plus a bibliography, complete the book.

Getting Slapped With a Lawsuit

Church Discipline and the Courts, by Lynn R. Buzzard and Thomas S. Brandon, Jr. (Tyndale, 271 pp.; $6.95, paper).

In addition to having to help people face death, disease, and perversity, the church and the pastor can get slapped with a lawsuit. In this cogently argued book, the authors say you can survive in a litigious society. They effectively defuse the fear of legal oppression that may have been fed by recent headlines.

Buzzard and Brandon begin by tracing the cultural roots of the recent trends. The rise of individualism and the loss of norms, authority and accountability, and the rejection of guilt (as a valid concept)—all have made people more willing to sue and juries more sympathetic.

A biblical survey and a quick run through church history provide ample justification for the duty of churches to discipline. They admit that there has been abuse by some churches and conclude that there is “no room for error” in the present climate.

This book’s real meat is found in chapters on procedures that will hold up under litigation; the legal aspects of confidentiality, defamation, and privacy; and the implications of someone resigning from the church during his or her disciplinary case. In each case, the authors indicate a line of legal defense in case you are sued. The authors are friends of the (church) court, showing how to proceed biblically and carefully. There is a path through the legal thicket.