Just south of Chicago’s Little Saigon, cars almost floated through water pooled in the streets after a day’s heavy rain. Drenched pedestrians on their way to or from one world or another sheltered under doorways and dashed inside well-lighted storefronts. From the sidewalk the tops of buildings blurred behind mist.

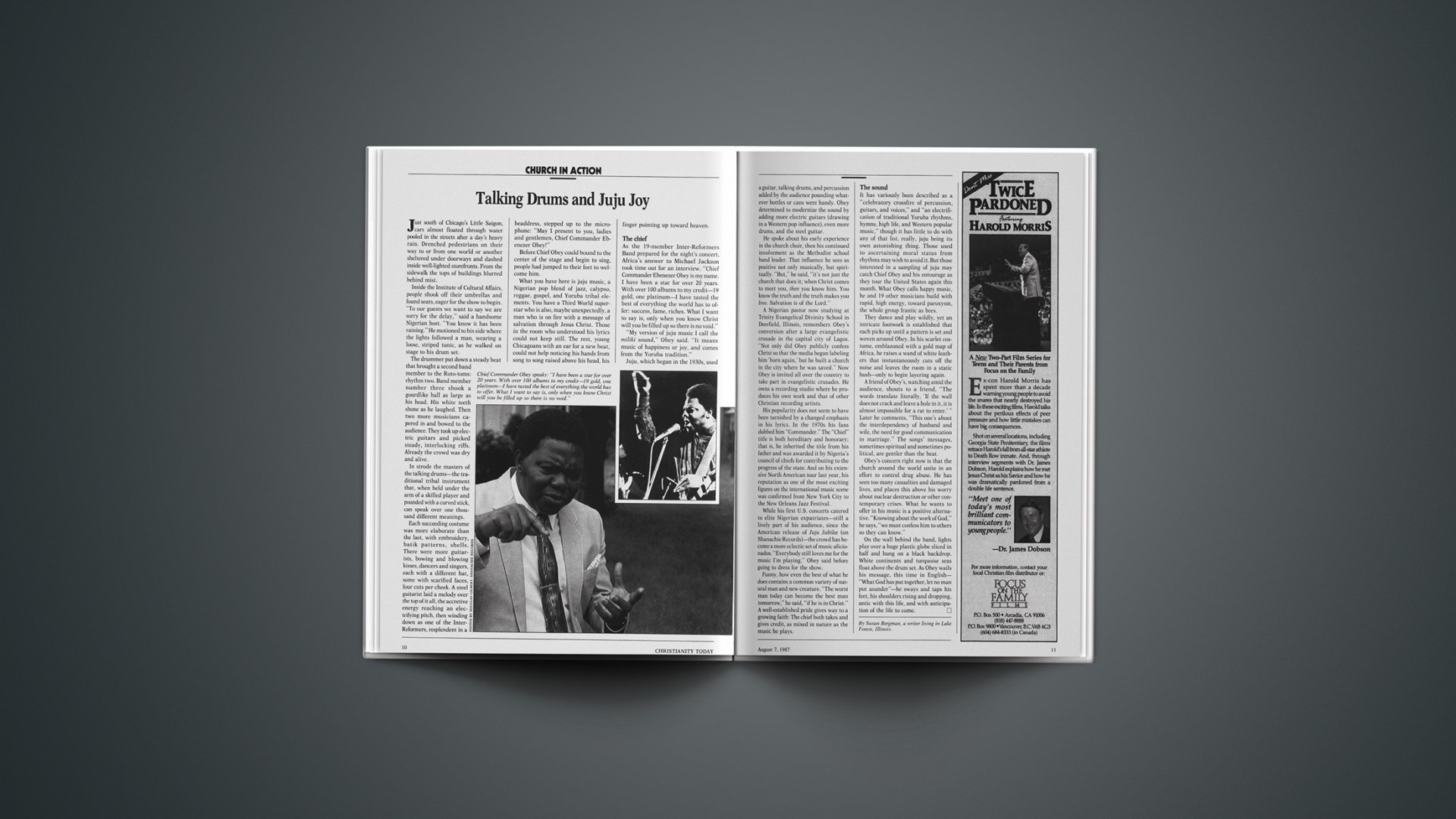

Inside the Institute of Cultural Affairs, people shook off their umbrellas and found seats, eager for the show to begin. “To our guests we want to say we are sorry for the delay,” said a handsome Nigerian host. “You know it has been raining.” He motioned to his side where the lights followed a man, wearing a loose, striped tunic, as he walked on stage to his drum set.

The drummer put down a steady beat that brought a second band member to the Roto-toms: rhythm two. Band member number three shook a gourdlike ball as large as his head. His white teeth shone as he laughed. Then two more musicians capered in and bowed to the audience. They took up electric guitars and picked steady, interlocking riffs. Already the crowd was dry and alive.

In strode the masters of the talking drums—the traditional tribal instrument that, when held under the arm of a skilled player and pounded with a curved stick, can speak over one thousand different meanings.

Each succeeding costume was more elaborate than the last, with embroidery, batik patterns, shells. There were more guitarists, bowing and blowing kisses, dancers and singers, each with a different hat, some with scarified faces, four cuts per cheek. A steel guitarist laid a melody over the top of it all, the accretive energy reaching an electrifying pitch, then winding down as one of the Inter-Reformers, resplendent in a headdress, stepped up to the microphone: “May I present to you, ladies and gentlemen, Chief Commander Ebenezer Obey!”

Before Chief Obey could bound to the center of the stage and begin to sing, people had jumped to their feet to welcome him.

What you have here is juju music, a Nigerian pop blend of jazz, calypso, reggae, gospel, and Yoruba tribal elements. You have a Third World superstar who is also, maybe unexpectedly, a man who is on fire with a message of salvation through Jesus Christ. Those in the room who understood his lyrics could not keep still. The rest, young Chicagoans with an ear for a new beat, could not help noticing his hands from song to song raised above his head, his finger pointing up toward heaven.

The Chief

As the 19-member Inter-Reformers Band prepared for the night’s concert, Africa’s answer to Michael Jackson took time out for an interview. “Chief Commander Ebenezer Obey is my name. I have been a star for over 20 years. With over 100 albums to my credit—19 gold, one platinum—I have tasted the best of everything the world has to offer: success, fame, riches. What I want to say is, only when you know Christ will you be filled up so there is no void.”

“My version of juju music I call the miliki sound,” Obey said. “It means music of happiness or joy, and comes from the Yoruba tradition.”

Juju, which began in the 1930s, used a guitar, talking drums, and percussion added by the audience pounding whatever bottles or cans were handy. Obey determined to modernize the sound by adding more electric guitars (drawing in a Western pop influence), even more drums, and the steel guitar.

He spoke about his early experience in the church choir, then his continued involvement as the Methodist school band leader. That influence he sees as positive not only musically, but spiritually. “But,” he said, “it’s not just the church that does it; when Christ comes to meet you, then you know him. You know the truth and the truth makes you free. Salvation is of the Lord.”

A Nigerian pastor now studying at Trinity Evangelical Divinity School in Deerfield, Illinois, remembers Obey’s conversion after a large evangelistic crusade in the capital city of Lagos. “Not only did Obey publicly confess Christ so that the media began labeling him ‘born again,’ but he built a church in the city where he was saved.” Now Obey is invited all over the country to take part in evangelistic crusades. He owns a recording studio where he produces his own work and that of other Christian recording artists.

His popularity does not seem to have been tarnished by a changed emphasis in his lyrics. In the 1970s his fans dubbed him “Commander.” The “Chief” title is both hereditary and honorary; that is, he inherited the title from his father and was awarded it by Nigeria’s council of chiefs for contributing to the progress of the state. And on his extensive North American tour last year, his reputation as one of the most exciting figures on the international music scene was confirmed from New York City to the New Orleans Jazz Festival.

While his first U.S. concerts catered to elite Nigerian expatriates—still a lively part of his audience, since the American release of Juju Jubilee (on Shanachie Records)—the crowd has become a more eclectic set of music aficionados. “Everybody still loves me for the music I’m playing,” Obey said before going to dress for the show.

Funny, how even the best of what he does contains a common variety of natural man and new creature. “The worst man today can become the best man tomorrow,” he said, “if he is in Christ.” A well-established pride gives way to a growing faith: The chief both takes and gives credit, as mixed in nature as the music he plays.

The Sound

It has variously been described as a “celebratory crossfire of percussion, guitars, and voices,” and “an electrification of traditional Yoruba rhythms, hymns, high life, and Western popular music,” though it has little to do with any of that list, really, juju being its own astonishing thing. Those used to ascertaining moral status from rhythms may wish to avoid it. But those interested in a sampling of juju may catch Chief Obey and his entourage as they tour the United States again this month. What Obey calls happy music, he and 19 other musicians build with rapid, high energy, toward paroxysm, the whole group frantic as bees.

They dance and play wildly, yet an intricate footwork is established that each picks up until a pattern is set and woven around Obey. In his scarlet costume, emblazoned with a gold map of Africa, he raises a wand of white feathers that instantaneously cuts off the noise and leaves the room in a static hush—only to begin layering again.

A friend of Obey’s, watching amid the audience, shouts to a friend, “The words translate literally, ‘If the wall does not crack and leave a hole in it, it is almost impossible for a rat to enter.’ ” Later he comments, “This one’s about the interdependency of husband and wife, the need for good communication in marriage.” The songs’ messages, sometimes spiritual and sometimes political, are gentler than the beat.

Obey’s concern right now is that the church around the world unite in an effort to control drug abuse. He has seen too many casualties and damaged lives, and places this above his worry about nuclear destruction or other contemporary crises. What he wants to offer in his music is a positive alternative. “Knowing about the work of God,” he says, “we must confess him to others so they can know.”

On the wall behind the band, lights play over a huge plastic globe sliced in half and hung on a black backdrop. White continents and turquoise seas float above the drum set. As Obey wails his message, this time in English—“What God has put together, let no man put asunder”—he sways and taps his feet, his shoulders rising and dropping, antic with this life, and with anticipation of the life to come.

By Susan Bergman, a writer living in Lake Forest, Illinois.