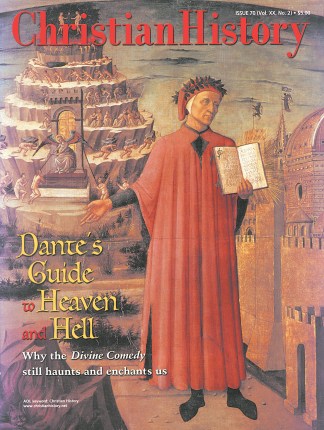

Big Man in the Cosmos

A giant in the world of which he wrote, laurel-crowned Dante stands holding his Divine Comedy open to the first lines: “Midway this way of life we’re bound upon, / I woke to find myself in a dark wood, / Where the right road was wholly lost and gone.” Of course, his copy reads in Italian. Dante was the first major writer in Christendom to pen lofty literature in everyday language rather than in formal Latin.

Coming ‘Round the Mountain

Behind Dante sits multi-tiered Mount Purgatory. An angel guards the gate, which stands atop three steps: white marble for confession, cracked black stone for contrition, and red porphyry for Christ’s blood sacrifice. With his sword, the angel marks each penitent’s forehead with seven p’s (from Latin peccatum, “sin”) for the Seven Deadly Sins. When these wounds are washed away by penance, the soul may enter earthly paradise at the mountain’s summit.

Starry Heights

In Paradiso, the third section of the Comedy, Dante visits the planets and constellations where blessed souls dwell. The celestial spheres look vague in this painting, but Dante had great interest in astronomy. One of his astronomical references still puzzles scholars. He notes “four stars, the same / The first men saw, and since, no living eye” (Purgatorio, I.23-24), apparently in reference to the Southern Cross. But that constellation was last visible at Dante’s latitude (thanks to the earth’s wobbly axis) in 3000 B.C., and no one else wrote about it in Europe until after Amerigo Vespucci’s voyage in 1501.

Doomed

The gate to Dante’s hell, on the left side of the painting, bore the dire message “Abandon hope, all who enter here.” Condemned sinners didn’t actually walk into hell but were ferried there by Charon, whom Dante borrowed from classical mythology. They were then sentenced by Minos, another classical figure, to their appropriate punishments. The very bottom of hell was not fiery, as this image seems to suggest, but a frozen lake.

Wanted: Dead

Dante was banished from his hometown of Florence (shown at right in the painting, which was commissioned for the Duomo—the domed building beneath the painted sun) in 1302 and threatened with incineration if he tried to return. But the poet made quite a name for himself in exile, and upon his death, in 1321, Florence wanted his body back. Ravenna, his adoptive hometown, refused. Florence repeated its demand a century and a half later, this time backed by Pope Leo X. Ravenna relented … or so it said. The city fathers actually shipped a sham coffin. Dante’s true remains were discovered in Ravenna in 1865 as the town was preparing to celebrate the 600th anniversary of his birth.

Screen Screams

In addition to countless paintings by artists from Sandro Botticelli to Salvador Dali, Dante’s Comedy has inspired several films. A silent Dante’s Inferno, released in 1924, was shot in black and white, but the fires of hell were elaborately tinted. In 1935 Spencer Tracy and Rita Hayworth appeared in a carnival-themed Dante’s Inferno, the slogan for which proclaimed, “It will burn in your memory forever!” More recently, the first eight cantos of Inferno were imaginatively recreated as A TV Dante for BBC Channel Four. The late Sir John Gielgud starred as Virgil.

Instant Classic

Students today may grumble about having to read the Comedy, but Dante’s contemporaries loved it. More than 600 fourteenth-century copies survive, attesting to its wide circulation. At least 12 commentaries had been written about it by 1400. Later it was among the earliest books to be set in movable type. But the poem lost favor with the rise of rationalism, and only three editions were printed in the seventeenth century. The Pre-Raphaelites helped bring the poem back into fashion in the nineteenth century, and its status now seems assured. More than 50 English translations of Inferno were published in the twentieth century alone.

Copyright © 2001 by the author or Christianity Today/Christian History magazine. Click here for reprint information on Christian History.