In this series

The chief imagination of Christendom,

Dante Alighieri, so utterly found himself

That he has made that hollow face of his

More plain to the mind’s eye than any face

But that of Christ. —W. B. Yeats

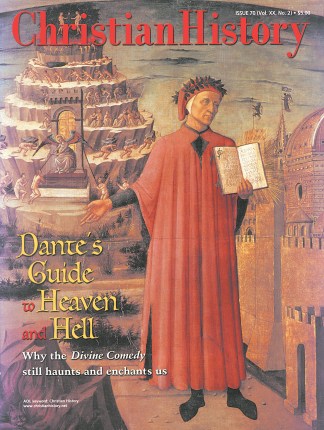

Scanning the “Book Review” section of the New York Times in 1999, I was surprised to see on the final page—a page generally devoted to a human interest story—the image at left. I will not speculate on the motivations of the editors for printing it; I doubt they were intending to further Christianity.

I can, however, guess what many readers were thinking: Science has brought us so far from that silly myth. But diagramming the great beyond was never Dante’s main objective. He was less interested in the question, “What happens when we die?” than the more pressing question, “How should we live in light of eternity?”

Is it not instructive that the picture in the New York Times needed no caption, no comment? Seven hundred years after Dante’s composition, his images remain familiar and forceful. This is because the principles that shape the images of the Divine Comedy, even if vehemently denied, still answer to something deep within the human consciousness. And it is the principles, not the images as such, that really matter.

What it is, and isn’t

Dante was fully conscious that he knew no more about the realities faced by departed souls than does anyone else. But as a mature Christian of his time, he was convinced of the reality of hell, purgatory, and heaven.

These convictions guided his fertile imagination as it speculated upon the concrete forms these realities might take. In giving them narrative embodiment, he expended great effort to achieve utter consistency, thoroughness, and comprehensiveness.

The form and structure of the Divine Comedy symbolize unity and completeness. The numbers three (for the Trinity), four (for man), and one (for final unity), as well as the “perfect” number ten, are omnipresent.

Consider the most obvious instances. The poem consists of three groupings of 33 cantos (poetic chapters) each, which, with the addition of the introductory canto, make 100, the square of 10. Dante’s terza rima stanzas consist of three lines each, with interlocking rhymes; the first and third line of each stanza rhyme with the second line of the previous stanza.

Each canto ends with a one-line stanza. Each of the three regions of the afterlife has ten compartments grouped into seven and three. Pythagoras is reputed to have said the world was created by number. Dante’s world certainly is.

The Divine Comedy offers compelling answers to many questions about the purpose of life and the principles of eternity.

The mythopoeic writers who follow in Dante’s wake—Edmund Spenser, John Milton, John Bunyan, George MacDonald, C. S.Lewis— each have strengths, but none rises to the same level of comprehensiveness. Furthermore, they all owe a debt to Dante, an obligation many of them overtly acknowledge.

Dante’s bedrock beliefs

Among the basic convictions that shape the story line of Dante’s great poem are these:

- People are responsible to God whether they know it or not.

- The human race was created by a loving God whose purpose was for people to choose righteously through life in order to see and be with God.

- Because people possess free will, their choices between good and evil shape their experience of life for time and eternity, and because decisions are shaped by desires, people must learn to desire God and his will.

- Right understanding leads to right conduct, while wrong choices frustrate God’s intentions and justly lead to negative consequences.

- Unforgiven sin diminishes sinners, depriving them of their very humanity, whereas Christian virtues enable people to develop into the full stature God intended them to have.

These principles must not be confused with the sometimes peculiar and eccentric images Dante uses to convey them.

God as Dante envisions him is no petty tyrant or vindictive divinity, as some cursory readers have concluded. Nor is Dante, writing as a political exile, a bitter curmudgeon gleefully assigning his friends to heaven and his enemies to hell.

Instead, the Divine Comedy presents a vision of the love of God evident in his government of the universe and in his grace expressed to humankind. The poem explores the central issues affecting the meaning and purpose of life and culminates in consuming praise for the wisdom of God’s ways.

One should not assume, however, that it is a great theological treatise buried within a curiously medieval narrative or an intellectual puzzle to decipher. Dante is doing his utmost to engage our imaginations. The Divine Comedy is first of all an engaging story and should be read as one would read a novel, fully imagining the images and identifying with Dante the character as he gives testimony of how he was led on a complete tour of hell, purgatory, and heaven.

In the beginning

In his famous opening lines, Dante introduces himself as a middle-aged man who was lost in a wilderness, having wandered from the right path:

Ay me! How hard to speak of it—that rude

And rough and stubborn forest! The mere breath

Of memory stirs the old fear in the blood;

It is so bitter, it goes nigh to death;

Yet there I gained such good, that, to convey

The tale, I’ll write what else I found therewith.

(Inferno, I.4-9)

The reader readily understands the allegorical level: Dante has sinned and is filled with distress and deep regrets. Whatever moral waywardness he had lapsed into, he profits from the experiences by coming to understand through them the nature of God. He acquires this knowledge, and shares it with his readers, as we travel with him through the realms of the afterlife.

Dante casts himself as an all-too-human pilgrim. He often seems just as bewildered as his readers by what he sees and learns from his guide Virgil, the image of the wisdom available to the natural man.

Virgil has been sent by the heavenly Beatrice, who allegorically represents the love of God expressed to humankind. The wisdom these two guides impart brings ecstasy to Dante the pilgrim, just as Christian truth thrills the soul and transforms it.

Because Dante at the beginning of the poem is astray in a “rough and stubborn forest,” his way up Mount Purgatory—which he sees in the distance—is blocked by a leopard, a lion, and a she-wolf. These signify respectively the sins of lust, pride, and fraud, acts that prevent people from attaining righteousness.

Only after Virgil has led Dante through the nether regions of hell, sternly impressing upon him the dehumanizing nature of all sins, can Dante understand the necessity of being freed from enslavement to them.

The hell through which Dante travels is a region God intended for Satan and his followers, not for people. Sinners adamant in their sins, however, inevitably and justly experience its myriad horrors.

The figures Dante meets as he funnels to the center of the earth are but the hulls of their former selves. They have, in Dante’s famous phrase, “lost the good of intellect” (Inferno, III.18) and become the sins they embraced.

The ultimate specimen is the great traitor Satan encased in Cocytus, the lake of ice at the center of the earth. The image of his immobility reinforces Dante’s emphasis upon free will and human responsibility. The inhabitants of hell may not blame Satan for their bad choices, because his power over them is severely limited.

Stairway to heaven

Readers who disagree with the doctrine of purgatory can nevertheless greatly profit from reading the second portion of the Divine Comedy. Whether one believes that the soul can be purified after death or that Christian maturity is pursued only on earth, the steps of growth that Dante experiences in purgatory are necessary for drawing nearer to God.

While climbing Mount Purgatory, Dante learns to desire God and his good above all else, then to see all things in relation to him, and to act accordingly. To achieve this knowledge he must be freed from the Seven Deadly Sins: pride, envy, wrath, sloth, covetousness, gluttony, and lust. These natural tendencies must be replaced with the Christian virtues of humility, generosity, meekness, zeal, liberality, temperance, and chastity—all components of that holiness without which no one will see God.

In medieval Catholic theology, the qualities one has not acquired by the time of death must be gained in the next life. No careful reader of the Divine Comedy, however, can conclude that Dante is suggesting a Christian can afford to neglect virtues now, or that they are purely the product of human effort.

Triumphing over sins and mastering virtues here and now are tasks Christians dismiss to their own inevitable sorrow. Dante sympathizes with the largeness of the task and eagerly points his readers to the beauty and glory of the prize.

The process of becoming holy is initiated by conversion: the three steps leading to the gate at the base of Mount Purgatory (canto IX) signify confession, contrition, and blood satisfaction. The necessity of dying to the tyranny of sin is suggested by Cato, who guides Virgil and Dante up the mountain. Cato was a Roman statesman who, rather than submit to Caesar, committed suicide.

The rule of the mountain is that none can climb by night: God’s enabling grace, symbolized by the sun, gives the essential light.

At the top of Mount Purgatory Dante enters the Earthly Paradise—he has been restored to the condition of unfallen man. He has achieved wholeness of being in righteousness. Virgil bids him farewell with the benediction:

No word from me, no further sign expect;

Free, upright, whole, thy will henceforth lays down

Guidance that it were error to neglect,

Whence o’er thyself I mitre thee and crown.

(Purgatorio, XXVII.139-142)

At the top of the mountain, Dante receives the heavenly Beatrice as his guide. The glories into which she then leads him stand quite beyond the reach of natural reason.

In real life, Dante had met Beatrice only once when both were children and once again nine years later, but he was always attracted to her as the very incarnation of divine love. Although both she and he married other spouses and she died as a young woman, her image inspired him throughout his life.

Allegorically, Beatrice unites both eros and agape—love as desire and as self-giving. From heaven she commissions Virgil to help Dante regain the right road. In seeing natural reason and loving relationships as prime vehicles of the love of God, Dante is affirming that any aspect of life can be a vehicle of God’s grace.

Land of the free

In paradise Dante, guided by Beatrice, moves joyously through a world completely centered on God. Images of light, dance, and music abound. Since thinking rightly is indispensable to beatitude, Dante receives much theological instruction, mostly following the thought of Thomas Aquinas. He converses with saints who, no matter if they disagreed with one another on earth, are now perfectly united in love.

As Dante rises into the ultimate heights of heaven, he is enraptured by a momentary vision of the Triune God bathed in radiant light:

And so my mind, bedazzled and amazed,

Stood fixed in wonder, motionless, intent,

And still my wonder kindled as I gazed.

That light doth so transform a man’s whole bent

That never to another sight or thought

Would he surrender, with his own consent;

For everything the will has ever sought

Is gathered there, and there is every quest

Made perfect, which apart from it falls short.

(Paradiso, XXXIII.97-105)

Dante’s engulfing rapture depicts the true end of man, complete in righteousness, finding satisfaction, contentment, and peace in fellowship with God. His journey consummated, Dante closes his great poem by affirming that his will and his desire are now “turned by love, / The love that moves the sun and the other stars.”

Just another quest?

In shaping the great Christian myth, Dante inevitably turns many of the archetypal images of the mythological past—such as the hero, the quest, and the afterlife—on their heads. They are displaced by the Christian fulfillments they foreshadowed.

Consider the image of the hero. Homer’s warrior hero Odysseus succeeds in a grand search for glory and adventure because he is cunning, daring, resourceful, and proud. In the Divine Comedy, however, those traits land Odysseus in the eighth circle of hell.

Dante’s Christian hero, on the other hand, seeks not external glory but inner holiness. His quest, therefore, is the pursuit of virtues—such as self-sacrificing love, meekness, peacefulness, and moral purity—that are radically different from the arete, or manly excellence, modeled by the ancient Grecian warrior hero.

It is impossible to reconcile Christian virtues with the pagan ideal of the warrior-hero. Dante may be viewed, nevertheless, as attaining heroic status in a Christian sense, as he becomes the ideal of what God intends for humankind. He also sets the Christian standard for literary achievement.

Some Christians would argue with the finer points of Dante’s theology, but none can disagree with the principles that shape his work, nor has anyone found a more imaginative way to express them. Were Dante with us today, he may ask to be forgiven his images, but he would affirm with joy the truths they convey.

Rolland Hein is professor emeritus of literature at Wheaton College.

Copyright © 2001 by the author or Christianity Today/Christian History magazine. Click here for reprint information on Christian History.